On the 4th August 2019, Nuon Chea, second only to Pol Pot in the leadership of the Khmer Rouge, passed away. His death comes at a finely poised moment in the work of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), preceding the completion of his appeal against a conviction for genocide delivered on 16 November 2018. The passing of Nuon Chea therefore raises questions regarding the legacy of that court and in particular the recognition of genocide under the Khmer Rouge.

The ECCC was established in 2006 to prosecute “senior leaders” and those deemed “most responsible” for crimes perpetrated by the Democratic Kampuchea ‘Khmer Rouge’ regime between 1975 and 1979, under which 1.7 million people perished. The ECCC is an “internationalized” mechanism, enjoying UN support, inclusive of international and domestic judicial personnel, but incorporated within Cambodia’s existing judicial system and organs. Although the ECCC has delivered successful convictions against three Khmer Rouge figures for crimes against humanity in 2011 and 2014, it has also faced a number of serious challenges since starting work. These challenges have included accusations of political interference by the Cambodian government, funding shortfalls, and high staff turnover in key judicial organs.

For some Cambodian audiences, the slow progress of judicial proceedings has been accompanied by a sense of frustration at the limited number of prosecutions and the ailing health and passing of a number of key accused persons. The death of Nuon Chea highlights the legitimacy of these latter anxieties; with his passing, the number of former Khmer Rouge senior leaders still under the Court’s jurisdiction is reduced from four to one. Of his three co-defendants, Ieng Sary passed away in 2013, and Ieng Thirith passed away in 2015, having been found unfit to stand to trial in 2012. Nuon Chea – unlike Ieng Sary and Ieng Thirith – lived long enough to be convicted of crimes perpetrated during the regime. Alongside Khieu Samphan, the former Khmer Rouge head of state, he was convicted of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide against the ethnic-Vietnamese population. In contrast to Khieu Samphan, he was also convicted of genocide against the Cham Islamic minority group. This group were forbidden from expressing their religious and cultural identity, and specifically targeted for execution from 1977 onwards, with estimates of the death toll ranging from 100,000 to 500,000 of the 700,000-strong community. With a further set of cases against other Khmer Rouge figures seeming increasingly unlikely to make it to trial, Nuon Chea may be the only perpetrator convicted of this particular crime. His passing prior to his appeal being determined raises issues concerning the legal status of that conviction, with potential implications for the legal recognition of genocide perpetrated against the Cham.

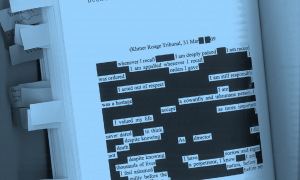

Mosque in Svay Khleang – Rachel Killean

The law on the implications of the death of an appellant is unclear. While other international courts, such as the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, have allowed judgments to stand when an appellant has died before the completion of an appeal, there is little consensus across legal regimes as to whether this is the correct approach. At the ECCC, neither the Law on the ECCC nor the Court’s Internal Rules provide clarity on this point. However, the Law of the ECCC declares that accused persons must be considered innocent until a ‘definitive judgment’ has been delivered, leaving open the possibility that only an appeal judgment might be perceived as satisfying the ‘definitive’ criteria. The Court’s rules are similarly unclear as to whether Nuon Chea’s appeal can continue following his death. This combined uncertainty raises the possibility that Nuon Chea will return to a state of being presumed innocent in relation to the genocide perpetrated against the Cham, revoking the only current legal recognition of that crime.

However, while there is obvious value in the legal acknowledgment of a genocide, it is worth noting that within Cambodia, a narrow focus on the ECCC as the only mechanism offering formal recognition of genocide is perhaps overstated. Indeed, situating different claims over the meaning of genocide in historical, social and political context remains crucial and presents important ethical questions in terms of how genocide is recognised and by whom. Domestically, a language of genocide was central to state building initiatives during Cambodia’s immediate recovery from the Khmer Rouge, such as commemorative activity, the school curriculum, and genocide convictions for Pol Pot and Ieng Sary in 1979. These proceedings, deemed an illegitimate ‘show trial’ by western governments, adopted a different and tailor-made definition of genocide from that contained in the Genocide Convention, which encompassed crimes perpetrated against the entire Khmer population. Such a framing, which more closely resembles modern understandings of ‘crimes against humanity’, demonstrates how understandings of genocide have been distinctly shaped within Cambodia since the end of the regime.

Looking beyond Cambodia, we might remind ourselves of the importance of the “politics of naming” genocide, given that western governments and the United Nations specifically did not recognise the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge as ‘genocide’ until the late 1990s, and often played questionable roles in supporting the Khmer Rouge insurgency during Cambodia’s civil war. While the Cambodian state continues to draw political legitimacy for their role in ‘ending the genocide’, and Cambodian communities have tended to describe and identify their experiences as ‘genocide’ since 1979, the lurch among western governments from positions of non-recognition to ‘genocide justice’ enthusiasts remains jarring. The outstanding question, here, is less that ‘genocide’ seems only recognized through the diagnostic apparatus of international criminal law, but that greater attention needs paid to both the histories of domestic and international politics that make naming ‘genocide’ possible, salient and meaningful.

The relationships between legal, political, social and cultural readings of past violence is further illustrated by a tendency among some Khmer communities to still see the ECCC as a vindication of their experiences of ‘genocide’, regardless of the framing of its legal judgments. The ECCC was presented as a national spectacle of renewal, that “everyone can be involved in”, and that could “set the record straight” for younger generations. As the legal process was ‘translated’ for public audiences, and even as these audiences have received and responded to the ECCC in uneven ways, the symbolism of guilty verdicts can carry more importance than the technical detail of the content of a judgement. Indeed, as Stephanie Giry notes, experiences of the Khmer Rouge have and continue to be understood through a set of historical, political and cultural meanings as an episode of ‘genocide’ affecting all Khmer people. Such social, cultural, and political meanings of genocide diverge from the legal definition adopted by the ECCC, which allowed only for genocide charges to be brought in relation to the ethnic-Vietnamese and Cham. This divergence is evident in the case of the Cham. Research conducted in this community in 2016 revealed that members of that community rarely drew distinctions between their experience and that of the broader Khmer population. Although aware of the restrictions placed on their cultural and religious practice, and the Khmer Rouge’s attempts to wipe out those forms of group identity, research participants were also clear that similar crimes had been perpetrated against the entire population. While keen for judicial recognition of their suffering through the ECCC, it was not apparent that there was a strong desire for a conviction in relation to a specific genocide perpetrated against their group.It is also worth considering the multiple forms of recognition that have been facilitated by the ECCC outside the context of legal judgments. Civil society organisations played a pivotal role in early ECCC public outreach campaigns, creating spaces for Cambodian communities to talk, in often differing ways, about their experiences of genocide and the ECCC as a response to it. More recently, civil society organisations have played a key role in developing and shaping a range of initiatives designed to provide ‘collective and moral reparations’ to the victims and survivors of the regime, ranging from psycho-social support to the reform of the school curriculum. As a result of the ECCC’s unique approach to reparations, these projects have in many cases been funded, delivered and completed prior to judgments being given. In the case of the Cham genocide, several of these projects have recognised and engaged with the Cham experience under the regime, including an exhibition ‘Raising Awareness of Cham and Vietnamese Experiences During the Khmer Rouge’ and the multi-media project ‘The Cham People and the Khmer Rouge’. While these measures were sometimes described by Cham research participants as insufficient to repair the full nature of their harm, they highlight the ways in which genocide recognition in Cambodia has extended beyond the legal sphere in ways that are unlikely to be significantly impacted by the possibility of Nuon Chea’s conviction losing its legal force. Indeed, the wording of the Court’s rules make clear that reparation claims are only brought to an end on the death of a ‘charged person’ or an ‘accused’, specifically excluding ‘appellants’, and seemingly therefore protecting the status of reparations awarded at trial.

Interventions intended to redress and reckon with experiences of genocide face a range of challenges. The application and rendering of the legal process does not occur in a vacuum. The technical questions it might wrangle with are not exempt from issues of politics, acknowledgement, and recognition, both in their formulation or resolution. Indeed, that a procedural question of genocide recognition in Cambodia remains so finely poised, contingent on the (foreseen) passing of an ageing perpetrator is instructive of the possibility that too much might be asked of law alone in such contexts. We should acknowledge too that harms experienced might carry multiple, varied and changing meanings for the communities that experience them that might diverge from – and converge with – the categories of international criminal law. Beyond the courtroom, institutions of international criminal law animate varied relationships with the communities that they are intended to benefit. These relationships are often complex and mediated within a wider web of creative community and non-governmental actors that each contribute to and shape understandings and expectations around responses to atrocities. The potential dilemmas for the ECCC in terms of genocide recognition arising from Nuon Chea’s death will require delicate and sensitive resolution. The broader questions these point to, surrounding different forms of acknowledgment and genocide recognition, will remain outstanding.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss