Malaysian democracy and civil society

The relationship between the concept of democracy and civil society is central to understanding the dynamics of the Malaysian system. The general concept of civil society goes back to antiquity as an arena between the state and the people; and took a peculiar meaning in the 1970s, an era marked by the political upheaval in Eastern Europe. Since then the concept of civil society has been prescribed as a pre-requisite for democracy and democratisation. Civil society has become a prism through which developing countries are evaluated by international agencies: “good” or “bad” governance, or “dictatorship or democracy”. Civil society would be one of the numerous milestones to pass when achieving a complete democratisation.

The growth and vibrancy of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as a main component of civil society, is utilised as an indicator of “progress” and the “quality of the NGOs and their network” has turned into a measure to evaluate the level of democratisation. NGOs have become a gauge of good governance – or at least improved governance. . This definition puts democracy as a system guaranteed and sustained by the existence of a civil society as the strongest and unquestionable bastion against abuse by the state apparatus. Interestingly the nature of NGOs is rarely challenged except when carrying religious messages, and more specifically towards Islam. Great attention has been paid to Islamic NGOs whose ideological inclinations have raised doubts, even more so in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks in New York.

In Malaysia, most NGOs are understood as occupying the political space in opposition to the ruling party in general, and thus to UMNO. In fact, any mention of pro-governmental NGOs remains rare in the analysis of Malaysian politics. However, there is a division within pro-opposition civil society organisations: between the Islamist on the one hand and the secular or non-religious organisations on the other. Thus when we look at connivance militants we are looking at a large slice of the public sphere that has been totally ignored.

The civil bluff

The independence of NGOs in the public sphere is questionable in Malaysia. A large number of NGOs in Malaysia are in fact embodying the interest of political parties, in different aspects; such as diffusing the party’s idea, supporting the party’s idea, supporting and/or getting involved in its public actions, initiating political action such as demonstrations or violence serving the party’s interest. Lee Hock Guan (2004)[i] reminds us that the limitations of the concept have not stopped observers, academics, and activists from using the term while being inspired from its western interpretation. But its definition should rather go along the parameters of the local political context.

Civil society in Malaysia dates back to the pre-independence period, when nationalism and political emancipation from colonial rule and most importantly citizenship rights, were organising forces. From the 1970s, the number of organisations, mostly crafted along ethnic lines more so than classist division due to deeply entrenched ethnic sentiments, continued to grow but “this growth did not necessarily translate into a democratisation process in all of them” since governments used and implemented a “combination of legal and coercive instruments to exert control” (Lee 2004:12).

Ramasamy (2004)[ii] explores an alternative perspective according which: (1) The state and civil society are not antagonistic, but share a relationship in the enforcement of domination; (2) Civil society is divided by pro and opponents to the state; (3) The state seeks to dominate civil society; (4) Civil society is an arena of contestation; the dominant will then own a method for manufacturing consent necessary for political domination; (5) It is an arena for competition and conflict of ideas in which the state may not dominate as non-state forces are participating.

However in Malaysia, the perception of civil society as being in opposition to the state, and the assumption that there exists a deep political divide between the two is still common. This view does not pay much attention to groups, or organisation, in association to the state or to political parties, more specifically to the ruling party. The way the NGO scene has been portrayed in the literature raises a few problems despite the warning by Lee (2004) and Ramasamy (2004).

The concepts of NGO and civil society, as understood in western literature, is inadequate for the Malaysian context for two main reasons: (1) NGO are by definition non-governmental and that implies independence vis-├а-vis the state and the government, and (2) the idea that civil society is often described as being an opposition force to governmental or state power. This simply means that the existence of NGOs that is pro-governmental or in close relationship to political parties, and even sometimes shadow surrogates of the state authority, has been completely ignored.

Protean disguise

Since the creation of the Federation of Malaysia in its contemporary geographical boundaries, the expressions of Malay nationalism were mainly to be found in the discourse and actions of the ruling party (UMNO) and it’s Youth Wing (Pemuda UMNO). While the Islamist party PAS was (and remains) the traditional ambassador of a more religiously conservative part of the Malay community. The emergence of new ethno-nationalist groups endorsed by the party’s old guard can be interpreted as a sub-contraction of UMNO’s pro-Malay discourse. The rising of these new groups pushing the Ketuanan Melayu (Malay supremacy) rhetoric should be seen as the preliminary emergence of a new fringe of civil society. These new entities were acting as pressure groups on the government by creating a non-party (and non-state) right wing – but until 2008 were not yet seen as constitutive of a coherent movement.

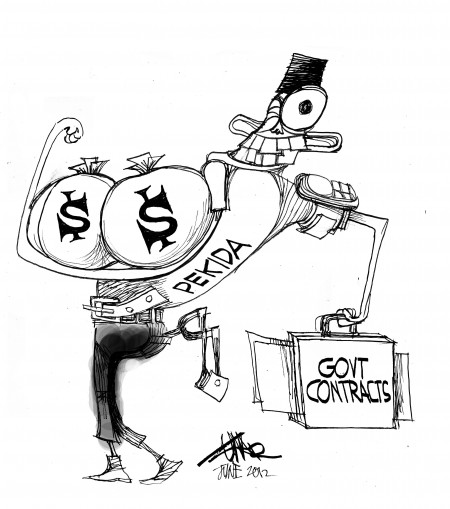

The realities of the political system are a summation of practices, mostly beyond the state’s legal frame, used to perpetuate power. The reality this research exposes is the creation of umbrella entities that were created to institutionalise and thus legalise the relationship between gangs and the ruling party. The liberalisation of the public sphere and the creation of new spaces of expression such as “civil society;” creates a fa├зade of free expression and development of “independent” bodies outside of the realm of the state – the non-governmental organisations – have set the ground for such institutionalisation.

The very existence, and need, for civil society has indeed favoured the development of this relationship while allowing the political involvement of gangs to be legalised through the creation of umbrella NGOs. This relationship – key to our study – has not been explored fully and the existence of pro-governmental NGO created to support the ruling party has been mostly ignored. In Malaysia “civil society” is in fact an aggregate of non-governmental organisations whose official purpose is to represent the people’s interests, framed by political and legal fetters that limit their actions. This virtual space should be seen as a civil extension of the political spheres where political parties’ surrogates and/or connivance militants, debate, demonstrate, and fight, arbitrated by the state rules. In that sense, civil society is a tool to create an official and legal umbrella for gangs and thus institutionalise their relationship with the ruling party.

The institutionalisation of gangs to NGOs has been initiated by the opportunities that arise in the post-Mahathir era. These opportunities emerged from exogenous and endogenous factors. First, following the resignation of Mahathir, there emerged a new space for NGOs created by the liberalisation of civil society. Secondly, in this context of relative liberalisation, the ruling party has had to face growing discontent relayed primarily through the alternative media and a stronger opposition. Some ruling party leaders have had the need for connivance militants. Thirdly, the leadership crisis that occurred at the death of PLB in 2006 precipitates the split of Pekida into several new branches each of which created its own NGO chapters to access the market of political militancy.

Informed observers have not noticed the presence of gangs in the political landscape mostly because these gangs are disguising (travestying[iii]) themselves. This potential to adapt to survive in any context has led these entities to adopt a timely form to publicise part of their activity (political militancy) while protecting others (illegal business). The political activities of connivance militants oscillate between the legal and illegal, licit and illicit.

Gangs have travestied into NGOs; traversing the frontier from the underground world to the light of the public sphere in order to offer support to political parties. In a different political, sociological, historical and geographical context, the ideological umbrella could have been leftist, anarchist, or feminist …etc.; and the main patron of these movements could have been any other political party in need for support – whether a ruling party or an opposition party. It is clear that the development of connivance militancy is favoured by a state’s opaqueness; nevertheless connivance militants groups may exist in every context. Their nature and action shaped according to the geographical, political, social and historical singularities.

Gangs are not just used as entrepreneurs of violence, but are part of the process of legitimising authoritarian power, a complex system not limited to Malaysia alone. With the new political challenges facing the ruling party vis-├а-vis the rise of the opposition, a need for reinforcing the system emerged. This need explains the reason why the political role of gangs has grown since 2008.

Nevertheless, the empowerment of gangs and the newly gained confidence of their leaders have fostered new ambitions. Some gang leaders, fearing a change of government and in the interest of preserving their access to resources, have turned to the opposition. This change in allegiance shows, as well, that the state system of legitimation has reached its limits, challenged by growing citizen awareness and increased access to alternative political discourse.

Gangs are part of the political system and should not be seen as an ephemeral phenomenon but rather structural entities with relative influence on the political scene, and able to adapt to contextual changes.

Part 1 can be read HERE, part 2 HERE and part 3 HERE.

Sophie Lemière is the Jean Monnet Postdoctoral Fellow at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy. She holds a PhD and a Masters in Comparative Politics from Sciences-Po (France). She is the author of Misplaced Democracy: Malaysian Politics and People.

[i] Lee Hock Guan (ed), (2004) Civil Society in Southeast Asia, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Studies. [ii] P. Ramasamy (2004), “Civil Society in Malaysia: An Arena of Contestations?” in Lee Hock Guan (ed) Civil Society in Southeast Asian, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. [iii] From the word ┬л travesti ┬╗ that means in French ┬л disguise ┬╗ Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss