We have seen significant transformation backed by digital innovation in Southeast Asia. Driven by growing disposable incomes and an abundance of affordable devices, the number of netizens is surging and the digital economy is rapidly expanding. From Learning and Development (L&D) programs to ride sharing applications, this digital wave offers new ways of rethinking supposedly tried-and-true approaches in business, government and everyday life.

Beneath this digital wave, Southeast Asia is characterised by a largely mobile phone-first population, which has led to a rise in mobile-gaming with an expected growth from 148.8 million in 2016 to 290.2 million gamers by 2023. This is reinforced by growing mobile phone penetration and expanding 5G technology. Alongside a well-established e-sports scene, Indonesia has recognised e-sports as an official sport and other governments are pursuing high-level partnerships with e-sports organisations. The enormous scale of e-sports is highlighted by a growing audience, which sat at just under 30 million in 2019, engaged with mobile gaming competitions with prize pools up to the $14 million range. These trends translate into deep-rooted familiarity with video gaming elements, positioning Southeast Asian audiences well to creatively utilise game mechanics in life beyond video gaming.

Gamification uses game mechanics and experience design to engage users. In some contexts, it can be applied to solve real world problems. This is done by aligning real-life behaviours with game mechanics, including experience points, multiplayer functionality and leader boards. However, gamification is not simply inserting colourful game mechanics in an organisational flow. Instead, it requires cohesive alignment with real-world objectives that have clearly defined goals. This can be seen in Foldit, an online puzzle game designed to better understand disease. Developed by scientists at the University of Washington, this game used high-score and multiplayer mechanics to tap into the human brain’s spatial reasoning abilities. In ten days, players successfully mapped out the enzyme structure of an AIDS-like retroviral disease, something that has baffled the scientific community for decades. This is noteworthy because this instance of gamified crowdsourcing surpassed automated computer algorithms.

Malaysia’s digital economy: can entrepreneurship be unleashed?

Crony capitalism in Malaysia may become a drag on the country’s digital ambitions.

Despite the numerous benefits of gamification, it can be counterproductive. Due to the wide variety of applications, gamification’s impacts are highly dependent on the context. One example is corporate use of gamification to introduce addictive experiences into business transactions. Many companies leverage the motivational affordances of gamification to compel customers into agreeing to the collection of their data through gamified loyalty programs. This often achieved through sensory overload via game mechanics, replacing rational decision making and distorting the individual autonomy of end-users. Moreover, the real-time feedback offered by gamification has resulted in excessive control and ranking of employees. Corporate giants like Amazon track staff productivity with handheld devices, distinguishing low and high performing employees with a point system. Low performing employees face disciplinary action including being fired. Steve Sims, Chief Design officer at Badgeville, comments on these haphazard uses of gamification to manage staff, ‘We like to think of it as behaviour management’.

Gamification can also incur high development costs. Depending on the scale of the gamified experience, potential development costs include designing original stock content, storyboarding and software testing. These issues highlight the importance of striking a balance of the numerous design elements consisting of the ethical considerations, contextual factors and the overall goals. Mike Brennan, president of a California-based digital transformation and HR consultancy, notes the need to keep a human-centered focus amidst gamification system design challenges, “A lot of this comes down to who are you designing the game for, what is the logic, what are the themes, what is the tone of the game and is it appropriate for the target population?”.

Well-designed gamification transforms tedious and time-consuming tasks into engaging experiences that encourage purpose-driven participation and collaborative activities.

Gamification has seen skyrocketing popularity in the Anglosphere with both technology giants like Google and public sector institutions like healthcare agencies adopting gamification in product and service design. With good reason, gamification is considered a powerful tool, not only because of its playful appeal, but because new technologies enable gamification to be highly measurable and scalable.

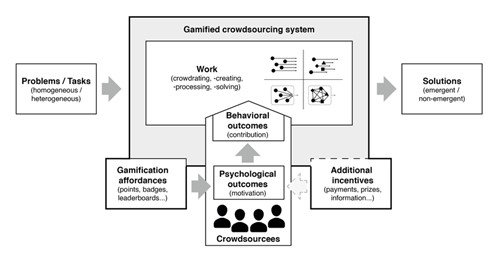

These attributes make gamification an ideal tool in crowdsourcing complex and inaccessible data. Benedikt Morschheuser created the following diagram to represent gamified crowdsourcing as a conceptual ecosystem, outlining behavioural affordances that boosts motivation and sense of achievement in attaining the defined outcomes. This framework is reinforced by incentives like virtual currencies and level up mechanics that rewards behaviours and habits, tapping into psychological motivations. These elements form an ecosystem that optimises collaborative data gathering to solve multi-layered challenges.

Conceptual Framework of Gamified Crowdsourcing Systems,

Benedikt Morschheuser et al (2017)

Experts are calling for adoption of more agile approaches in sourcing feedback, leading to shifts in technology regulation, information architecture and policy design. Gamified crowdsourcing is one the new ways in gathering data that will provide more responsive insights to governments. Erik Brynjolfsson, Director of MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, remarks that “governments are flying blind, they don’t have the data needed to understand what the opportunities are, what the risks are. Our gathering data infrastructure was a wonderful invention in the early twentieth century, but it is not keeping up with what we need to today”.

This approach is promising in addressing the widening engagement deficits between governments and civil society and responding to the fast-paced digital environment. The expansion of internet infrastructure, vast accessibility of mobile technologies and a well-established game culture in Southeast Asia showcases the many opportunities for gamification in the region.

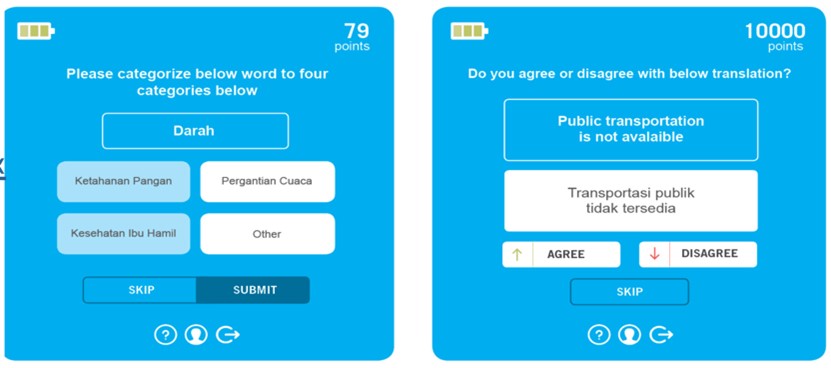

Translator Gator Phase 1

Translator Gator is a strong example of the potential for gamification to boost participatory engagement in developing better public policy. As part of a United Nations initiative called Pulse Lab, Translator Gator is a simple web-based matching game that crowdsources disaster-related translations for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to improve Indonesia’s natural disaster response. With Indonesia being of the most disaster prone and linguistically diverse nations, the first phase consisted of a web-based game to collect alternative translations for key phrases in the SGD’s. The player inputs were benchmarked for accuracy and catalogued into different categories. The simple game interface generated a comprehensive taxonomy of translations in lesser-spoken Indonesian languages like Bahasa Jawa, Sunda, Minang, Bugis and Melayu.

The Translator Gator webpage (http://translatorgator.org) is Creative Commons Licensed.

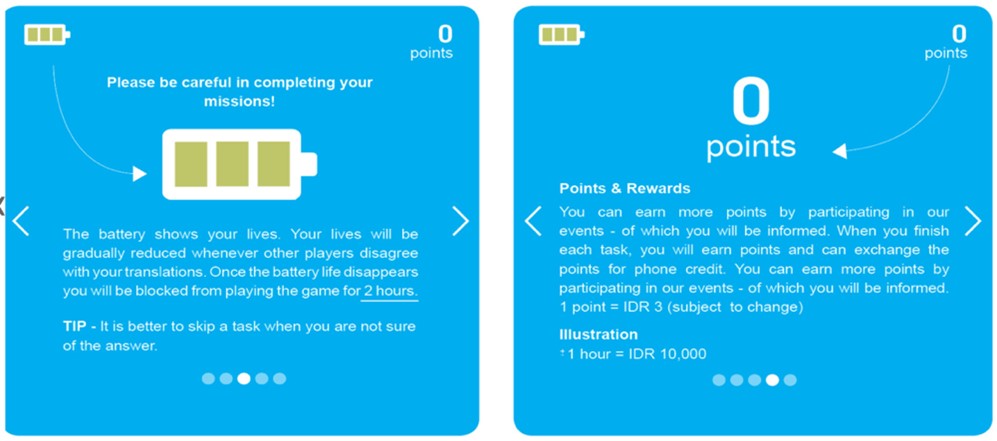

The game gathered keywords of nuanced language including local expressions and slang. This was critical as the SDGs contain technical language which are often challenging to communicate due to varying cultural contexts and limited existing SDG educational resources in local languages. Correspondingly, Translator Gator has a multiplayer peer review function that allowed players to assess the accuracy of other contributions. If a player submitted an incorrect translation, the player would be temporary kicked off, boosting motivation. The motivation effect of the gameplay was extended by a streak mechanism. This allowed players to view their progress, establish habits and encourage momentum in making more accurate translations of keywords.

Translator Game Mechanics

http://translatorgator.org/

Yulistina Riyadi, a research associate at Pulse Lab Jakarta, comments on the bottom-up approach of this gamified platform to “tap into the wisdom of the crowd.” Connecting civil society actors enables Translator Gator to be more inclusive, capturing insights at a more grassroots level.

These gamified functions not only encouraged gameplay. They established a rapid feedback loop that sustained player inputs and filtered accurate translations that were culturally responsive.

In addition to the motivations of the crowdsourced gamification framework, players were rewarded with virtual currencies that can be exchanged for real-world phone credit. This essential part of the design highlights the importance of tangible incentives in attracting player contributions. This is evidenced by spikes in gameplay that corresponded with redeem periods when players could obtain phone credit by exchanging their game points.

Greater rewards and social media integration

Translator Gator’s design attracted both language enthusiasts and the general public alike; the game attracted over 109,000 player contributions in the first month after its launch in 2016. The quality of player contributions is shown by data analysis indicating translations were 97% accurate, and which were later used in converting initial findings into data visualisations.

The focus on collaborative and tangible outcomes was continued by the establishment of a Research Dive on the theme of Natural Language Processing for Sustainable Development. This Research Dive was organised as a workshop bringing together 19 computational linguistic academics and experts from 18 different universities and government bodies. This cross-sector collaboration resulted in recommendations for the production of an open-access toolkit for Indonesian language processing and an extensive review of design flaws in Translator Gator’s first iteration.

Translator Gator Phase 2

Following the success of the pilot, the second phase of Translator Gator highlighted the enormous scalability of gamified platforms by expanding country range and increasing integration with social media ecosystems. This phase was more research-oriented, designed to consolidate crowdsourced disaster-related translations in order to inform public policy at a decision-making level.

The enlarged country range consisted of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka. Although the system was not without its flaws, the expansion resulted in the development of culturally responsive taxonomies in a further 28 languages, ten of which extended to over 80% of the relevant dictionaries. This is an impressive feat, considering the significant variations in scripts, grammar and syntax in the region. Similar to the first phase, the response highlights widespread familiarity with game mechanics, easing participation to the transnational goal of improving disaster response strategies.

To match the increased range, Translator Gator introduced new incentives to encourage gameplay in the region. The game announced a referral system that rewarded existing players with extra points in exchange for referring new players to the platform. As Southeast Asia is a largely mobile-phone first demographic with heavy social media usage, this strategy was effective in attracting new players to Translator Gator. Deeper integrations on social media were reinforced by prizes beyond phone credit, including vacations to Bangkok and Jakarta, gift vouchers and merchandise.

Intriguingly, the success of Translator Gator illustrates a gap between current policy making and rapidly changing technologies. Although the sense-and-respond largely associated with software development and business efficacy, the principles are highly relevant in structuring crowdsource functionality. With Translator Gator, software teams and broader technology organisations noticing constantly changing user interactions with products, the need to respond to the continually changing nature of technology is realised. Accordingly, sense-and-respond endorses multiple iterations and quick responses through constantly seeking feedback. The focus on constantly pivoting and gathering real-time feedback in gamified policy design shows that policymakers need to constantly be learning and updating. This is essential in developing more agile and well-informed policy.

Ov erall, the scaled impact of the second phase of Translator Gator is highlighted by the approximately 1.5 million gaming activities performed by nearly 4,000 registered players. The contributions were consolidated into an open-source database available for public viewing.

erall, the scaled impact of the second phase of Translator Gator is highlighted by the approximately 1.5 million gaming activities performed by nearly 4,000 registered players. The contributions were consolidated into an open-source database available for public viewing.

Gamification for good?

Other civil society groups and governments have also begun to integrate gamification with public service technology. Examples include Singapore’s ActiveSG platform that encourage fitness, the United States’ “What’s the Point”, which crowdsources resident feedback on infrastructure development in a Massachusetts town, and the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs’s “Kangazoo” game that uses open world mechanics to educate players about Australia’s unique biodiversity and positive environmental responsibility.

Instead of predicting policy outcomes based on fixed data and top-down leadership, governments would benefit from adopting a more creative and bottom-up approach in responding to rapidly changing environments. Gamification is a powerful way to achieve this, enabling grassroots participation by design.

However, gamification as a tool for participatory governance is not always a silver bullet. As a design practice, the essentials of clearly defined goals and purpose-driven participation are questionable when leveraged for ethically unsound purposes. During both Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton’s presidential campaigns, gamification was utilised to attract potential voters. From virtual points rewarding the promotion of candidate profiles to synchronising tweets with social media accounts, the growing role of gamification in the political landscape is apparent. Another example is Israel Defence Forces’ (IDF) virtual army game that rewards players sharing depictions of air-strikes on social media. The IDF was criticised for cartoon-like rendering of the destruction of targets, simplifying the political and strategic complexities of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Ultimately, this is illustrative of the concerns of this gamified platform, dehumanising the deadly impact of air-strikes.

These ethical and technological issues illustrate a broader problem in the regulation of the rapid pace of technological development. This conundrum has driven Agile Governance for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, a broader movement that seeks more responsive regulation on a range of unprecedented issues including gamification, that have been introduced by emerging technologies.

In Southeast Asia, harnessing the high digital penetration rates and maturity of video-gaming culture will be key to designing more inclusive, technology-enabled policy engagement. Governments should support cross-sector partnerships to establish linkages between demographics and emerging technologies in order to co-design robust solutions. This bridges computational data and ethno-linguistics, which will be key in responding to a future marked by the challenges and opportunities of new technologies.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss