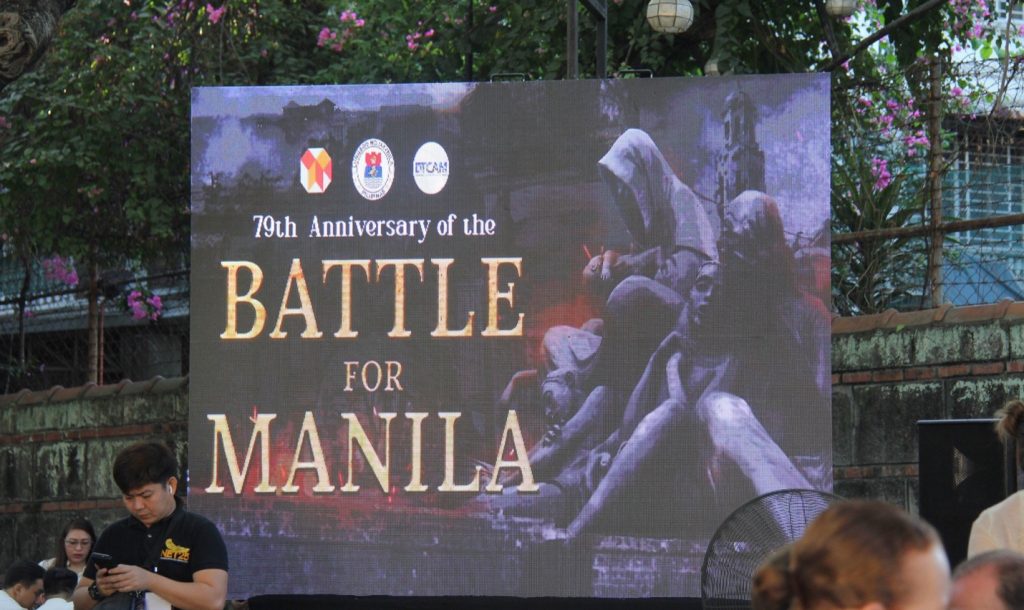

On 3 February, 2024, the Manila City Government marked the 79th anniversary of the Battle of Manila with a solemn but subdued ceremony. The event was attended by a select group of dignitaries, including ambassadors and representatives from various Philippine government entities and civic organisations. The site of the gathering was the Memorare Manila Monument, a poignant memorial erected in 1995 through the effort of the survivor group Memorare Manila 1945 and dedicated to the memory of the over one hundred thousand non-combatant civilians who tragically lost their lives during the intense month-long battle. The group holds its own commemoration rites, aiming to raise consciousness about the battle that, in their view, hardly anyone remembers.

World War II commemoration in the Philippines is deeply embedded within the nation’s collective consciousness, manifested through national holidays, historical landmarks, and the personal stories handed down by those who endured the war’s severe hardships. This practice of remembrance serves as a testament to the enduring impact of the war on Filipino society and culture. However, the contrast in the manner of commemorating the Battle of Manila with the more prominent celebrations of the National Day of Valor, observed with much pomp and circumstance on April 9 each year, is striking. The latter, a public holiday established in the 1960s, remembers the Fall of Bataan and the subsequent surrender of US and Filipino soldiers to Japanese forces in 1942.

Contrasting the commemoration of wartime Bataan and the Manila reveals a disconcerting reality. While Bataan is nationally celebrated, Manila is largely forgotten in the nation’s collective memory. The month-long battle, from February to March 1945, was characterised by extensive civilian casualties and such severe property destruction that Manila has been recognised as the most devastated Allied capital in the Pacific and the second most destroyed in the world, next to Warsaw, Poland. The battle’s conspicuous absence from popular memory is particularly striking, considering its profound historical significance.

As a historian studying war memories in the Philippines, I find the relative obscurity of the Battle of Manila in collective memory quite perplexing. My experience as a Filipino academic residing in Hiroshima further magnifies this sentiment. Devastated during the war, Hiroshima has emerged as a global symbol of the horrors of nuclear weapons and a rallying point for peace and nuclear disarmament. The city’s annual commemorative rituals are intricate, and its memorials, centrally positioned within the cityscape, not only serve as poignant reminders of the past but have also evolved into major tourist attractions.

In stark contrast stands Manila, a city that likewise endured immense wartime destruction. Here, the remembrance of the Battle of Manila is markedly subdued. There seems to be a conspicuous lack of initiative from the national government to formally acknowledge or commemorate this pivotal historical event. Instead, the commemorative effort is primarily driven by private entities and individuals. This striking disparity in how the two cities approach their wartime legacies raises intriguing questions about national memory, the politics of remembrance, and how societies choose to confront or overlook their historical traumas.

The Battle of Manila led to the ruin of the Philippine capital city in 1945. Pictured here is Intramuros after the battle. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Selective memorialisation

Why has the Philippines forgotten the Battle of Manila? To answer this, looking into what aspects of the country’s war past have been memorialised is integral. Following World War II, the Philippines embarked on a mission to commemorate its wartime experiences, initiating the process in the late 1940s through the national effort to install historical markers across the country.

This effort gained momentum in 1954 when president Ramon Magsaysay designated the war sites of Bataan and Corregidor as national shrines, acknowledging their importance as sites of the combined Filipino and US effort to fight the Japanese but only ended in defeat in 1942. In 1961, 9 April was declared a national holiday by the Philippine Congress, initially as Bataan Day, later renamed the Day of Valor, to honor the Fall of Bataan.

The emphasis on memorialising Bataan and Corregidor further intensified during Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s presidency. Marcos, asserting his wartime heroics in Bataan, heavily influenced the creation of the Shrine of Valor where he played a direct role in both the memorial’s planning and ceremonial cornerstone laying. This monument became a central symbol of the war in the Philippines. Concurrently, the United States constructed the Pacific War Memorial on Corregidor Island as the main site of US memorialisation of the war in the Philippines.

It must be noted, however, that the creation of these two memorials occurred with the Cold War as a backdrop, a time when the Philippines maintained a strong alliance with the United States and a period marked by anti-communist campaigns. This geopolitical background significantly influenced how World War II was commemorated in the country, particularly in the prominence given to sites like Bataan and Corregidor.

Despite its significant historical role, the Battle of Manila did not attain the same level of commemoration as the Falls of Bataan and Corregidor. The attention given to Bataan and Corregidor underscored the special bond between the Philippines and the United States, embodied in the narratives of US–Filipino solidarity formed amidst conflict.

In contrast, Manila’s less prominent memorialisation might be attributed to the focus on US-Filipino collaboration against a common enemy and the strategic importance of emphasising certain aspects of the war that aligned with contemporary political and ideological agendas. Additionally, by highlighting the military aspect of the war, the memorials of Bataan and Corregidor promoted ideals of duty and loyalty, countering the perceived threat of the communist movement and supporting the government’s domestic anti-communist stance.

Post-war administrations in the Philippines favored a military-centric narrative, overshadowing the experiences of prisoners of war, women, children, and civilians. This selective narrative predominantly celebrated military heroism, shaping the collective memory of the war in a specific manner.

State-sponsored war memorial sites in the country overwhelmingly spotlighted the military’s role, honouring soldiers and guerrilla fighters, often at the expense of recognising civilian suffering. Soldiers’ deaths were portrayed as noble sacrifices, promoting values of selflessness and serving national interests.

In my analysis of war memorial sites in the Philippines, I find that they promote the notion that peace is merely the absence of war. This message implies that war is sometimes necessary, and the nation must be prepared for future conflicts. This advocacy paradoxically undermines the ability of these memorials to promote lasting and meaningful peace.

The places that once were: remembering Marawi

Reconstruction efforts need to consider the role of spaces and images in building peace.

Interestingly, another memorial structure was placed around the same area not too long ago. In 2017, a memorial to Filipina comfort women was installed here, overseen by the Manila city government and the National Historical Commission of the Philippines. It featured a grieving, blindfolded Filipina woman dressed in the traditional Maria Clara attire. The installation drew urgent responses from the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs and officers from the Japanese Embassy.

Indeed, the statue was short-lived—four months later, the Department of Public Works and Highways removed the statue for a drainage improvement project in the area, drawing flak from activists and some lawmakers. Reacting to the criticism of the monument’s removal, former President Duterte stressed that the statue could be placed elsewhere since it is not his government’s policy to antagonise other nations.

What this removal tells us is that certain war memories are prioritised by the government, such as the military narratives evoked in the battle tank monument, while there are war memories that the government cannot sponsor — such as that of the civilians like the comfort women. Who leads the memorialisation of the war’s civilian victims in the country?

There are non-state civil society groups such as comfort women activists and organisations that lead commemorative efforts and the building of memorial structures. For example, The Battle of Manila is the focus of the memorial Memorare Manila 1945 in the district of Intramuros. While the monument was erected through civilian effort, the National Historical Commission of the Philippines placed a historical marker on the site. Here, an annual commemoration in memory of civilian victims takes place every February. However, it is civil sector-led, and attendance is usually limited to organisers and peace advocates. An exception was in 2006, when the Japanese ambassador to the Philippines attended the commemoration and apologised for Japanese military atrocities against Filipinos.

Conclusion

Over a million civilians perished during World War II in the Philippines, yet the country’s memorial sites predominantly honor the bravery of soldiers and guerrilla fighters. This selective commemoration highlights the curated nature of national memory and emphasises the necessity for a broader and more authentic portrayal of the war’s repercussions.

Acknowledging and memorialising all facets of the war — especially the frequently neglected experiences of civilians — is essential for the nation to fully understand its history, heal from its wounds, and pave the way for a more peaceful future. It is crucial that both the government and civil society unite in their efforts to create a more holistic and equitable narrative of World War II in the Philippines, ensuring that the tribulations and sacrifices of all affected are duly recognised and respected.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss