Indonesia’s political landscape has changed over the past five years: while it was once described as a country without serious ideological conflict or partisan competition, experts now cast its politics as increasingly polarised.

Usually when analysts talk about polarisation, they’re referring to a partisan divide along party lines. American society, for example, is deeply divided between Republicans and Democrats. In surveys, around 60% of Americans say they feel close to one of these major parties, and party choice reflects a range of policy preferences. If someone supports the Republican Party, for example, we can pretty accurately predict their position on gun control, immigration policy, and abortion.

In Indonesia, on the other hand, the vast majority of voters feel very little attachment to political parties. What political scientists call “party identification”—the proportion of voters who express a personal identification with a party—is now at 12%, based on a survey conducted in May 2019 by the Indonesian Survey Institute (LSI) and the Australian National University (ANU). Most parties are catch-all and patronage-driven, and their policy positions vary little. Even when it comes to parties with a clearer ideological orientation, partisanship is remarkably low: the same 2019 LSI–ANU survey showed, for example, that only 3.3% of all respondents feel “close” to the most pluralist party, PDI-P, and 1.5% feel “close” to one of the most Islamist parties, PKS. These sorts of figures have led most analysts to conclude that partisanship is weak in Indonesia.

But personalities, not just parties, can attract strong partisan loyalty. As levels of party identification have eroded in democracies all around the world, politics have become more personalised. In Indonesia’s presidential system, where citizens vote directly for their president rather than for a party, personalities have always mattered. But over the past five years, Indonesia has experienced unusually intense competition between President Jokowi and Prabowo Subianto. Both are charismatic leaders with their own populist style. Since their first electoral contest back in 2014, these two men have dominated national politics and, in the process, built a base of loyal followers.

Their constituencies reflect an old religio-cultural divide between pluralists and Islamists that has long characterised Indonesian society. Jokowi enjoys the support of more traditionalist Muslims, mostly in East and Central Java, and he is immensely popular with non-Muslim minorities and more secular-oriented Indonesians. Prabowo, on the other hand, is popular in modernist and conservative Muslim communities, mainly in West Java, Sumatra and parts of Sulawesi. The 2019 presidential election produced an electoral map that reflected this divide.

Measuring the ‘NU effect’ in Indonesia’s election

Ma’ruf Amin's electoral benefit was smaller than often assumed—but it was enough to get Jokowi over the line.

To test this hypothesis, we ran a series of survey experiments in December 2018 in which we informed respondents about a contemporary policy debate and asked them to indicate their own position on that policy. The control group received no political cue, while a treatment group was told that Jokowi supports one position and Prabowo supports the other. The scenarios presented to respondents reflected real-word policy debates and actual positions taken historically by Jokowi and Prabowo, or by parties in their coalition.

The results were striking. Across a range of policy areas, from imports, income inequality, electoral laws, to foreign debt and investment, cues from these two political leaders shifted partisans’ policy preferences. We present the descriptive statistics below for three illustrative examples. We believe the results have important consequences for how we understand the nature of partisanship in Indonesia, how we measure voters’ policy preferences, and how we gauge popular support for Indonesia’s key democratic institutions.

Experiment 1: preference for reducing imports

Respondents were questioned about their thoughts on the level of imports into Indonesia. The table below outlines the number of Jokowi partisans, Prabowo partisans, and non-partisan respondents in each group.

| PARTISANSHIP | CONTROL | LEADER CUE (Jokowi/Prabowo) |

| Joko Widodo and Ma’ruf Amin | 226 | 212 |

| Prabowo Subianto and Sandiaga Uno | 146 | 133 |

| DK/DA/Won’t vote | 42 | 50 |

The control group received the following information:

During the campaign for the 2019 presidential elections, there has been much debate about imports. I am going to read you some opinions on this issue.

1. Some groups believe that Indonesia should stop importing goods and basic food items from overseas, because imports threaten the prosperity of local farmers and business owners.

2. Other groups believe that Indonesia should be importing goods and basic food items because there isn’t enough local stock, and local farmers and businesses also aren’t threatened by imports.

Of these two opinions, which is closet to your own?

1. Opinion A; 2. Opinion B; 3. Don’t know/Didn’t answer

Then, respondents in the treatment group were given the same information, but this time with leader cues: Opinion A read “Prabowo argues that…”, and Opinion B read “Jokowi argues that…”

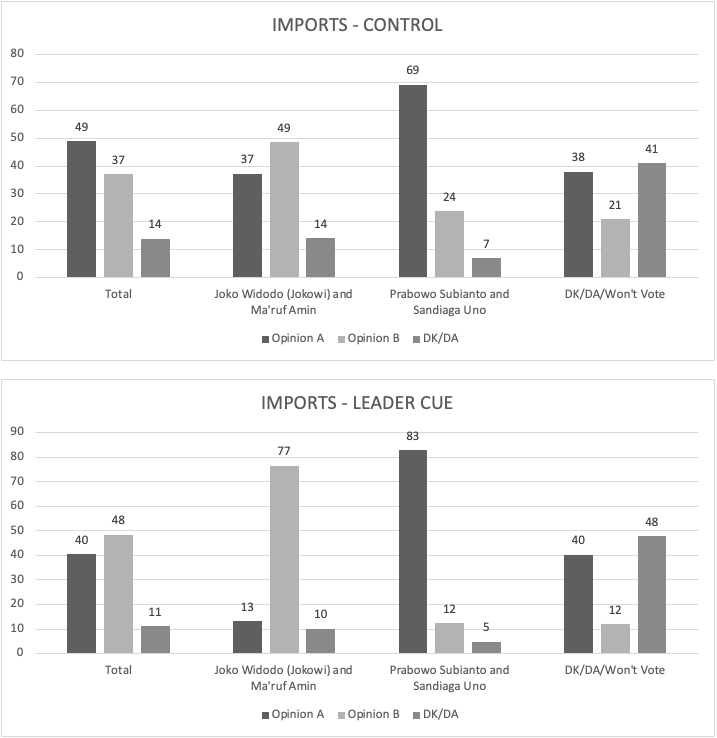

The results are displayed below. (Click to enlarge)

The data indicate that public opinion on this issue is already polarised even without being exposed to leader cues. A strong majority of Prabowo supporters are opposed to foreign imports. These results are not surprising, because Prabowo has long cast himself as a champion of Indonesian farmers, local business, and as stridently nationalist in his economic outlook. Jokowi voters in the control group, on the other hand, are more divided on this question of imports.

Once leader cues are introduced, however, partisans polarise more dramatically. Now 83% of Prabowo supporters oppose imports, and 77% of Jokowi voters believe imports are necessary. The differences between responses in the control group and the treatment group for both Prabowo and Jokowi partisans are statistically significant.

Experiment 2: support for the Perppu Ormas

We asked a question about the controversial decree on mass organisations (known as the Perppu Ormas), which was enacted in 2017 to allow for the dissolution of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI). The table below outlines the number of Jokowi partisans, Prabowo partisans, and non-partisan respondents in each group.

| PARTISANSHIP | CONTROL | LEADER CUE (Jokowi/Prabowo) |

| Joko Widodo and Ma’ruf Amin | 228 | 213 |

| Prabowo Subianto and Sandiaga Uno | 136 | 135 |

| DK/DA/ Won’t vote | 54 | 49 |

The control group received the following information:

Some time ago, there was much public debate about the Government Regulation to Replace the Law on Societal Organisations (Perppu Ormas). I am going to read you some opinions on this issue.

1. Some groups believe the government has used its power arbitrarily, because the Perppu Ormas violates people’s right to organise.

2. Other groups believe that the government has legitimate authority to outlaw community organisations that threaten Indonesia and violate the Pancasila.

Of these two opinions, which is closet to your own?

1. Opinion A; 2. Opinion B; 3. Don’t know/Didn’t answer

Then, respondents in the treatment group were given the same information, but this time with leader cues: Opinion A read “Prabowo argues that…”, and Opinion B read “Jokowi argues that…”

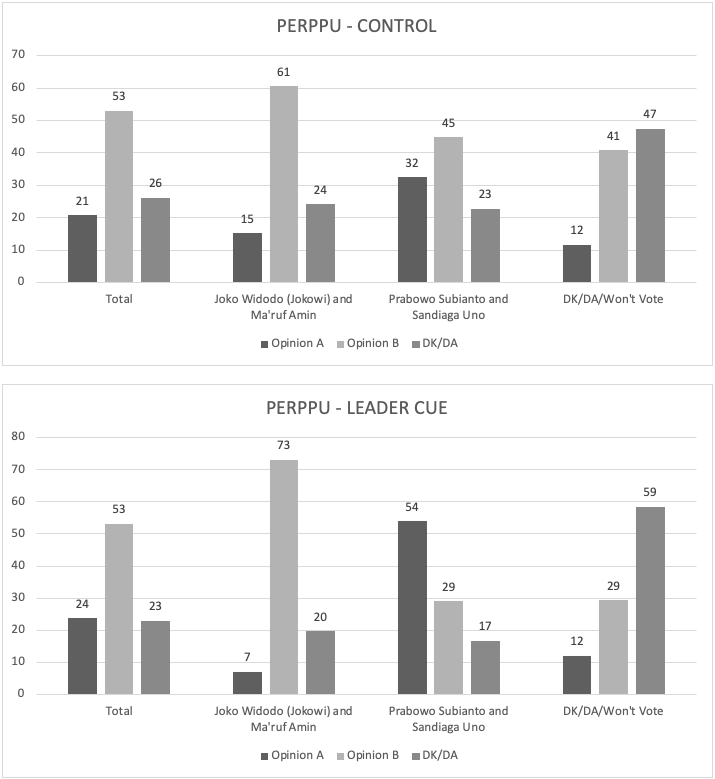

The results are displayed below. (Click to enlarge)

The results suggest again that opinion on this issue is already polarised, with a strong majority of Jokowi supporters in the control group believing that the government has a right to shut down groups it deems threatening. Prabowo supporters are more divided, but a majority feel the same way as most Jokowi supporters.

However, when leader cues are introduced, a strong majority of Prabowo supporters agrees with Opinion A—that the government has acted arbitrarily and in violation of citizens’ right to organise. The number of Jokowi partisans that agree with the Perppu, meanwhile, increases to 73% when they are told that Jokowi himself has argued in favour of the law. Again, the differences between the control and treatment groups are statistically significant.

Experiment 3: support for regional elections

The table below outlines the number of Jokowi partisans, Prabowo partisans, and non-partisan respondents in each group, who were asked about the maintenance of direct elections of regional executives (Pilkada).

| PARTISANSHIP | CONTROL | LEADER CUE (Jokowi/Prabowo) |

| Joko Widodo and Ma’ruf Amin | 226 | 216 |

| Prabowo Subianto and Sandiaga Uno | 136 | 145 |

| DK/DA/Won’t vote | 54 | 36 |

The control group received the following information:

The direct election of regional heads (Pilkada) has become the subject of debate recently. I am going to read you some different opinions on this issue.

1. One side argues that direct election of regional heads by the people has become too expensive and produces corruption, and therefore the system should be changed so that regional heads are chosen by regional parliaments (DPRD).

2. On the other hand, some people argue that direct election of regional heads must remain in order to protect the people’s sovereign right to choose their leaders, and because having local parliaments choose regional heads will not prevent against corruption or money politics.

Of these two opinions, which is closet to your own?

1. Opinion A; 2. Opinion B; 3. Don’t know/Didn’t answer

Then, respondents in the treatment group were given the same information, but this time with leader cues: Opinion A read “Prabowo argues that…”, and Opinion B read “Jokowi argues that…”

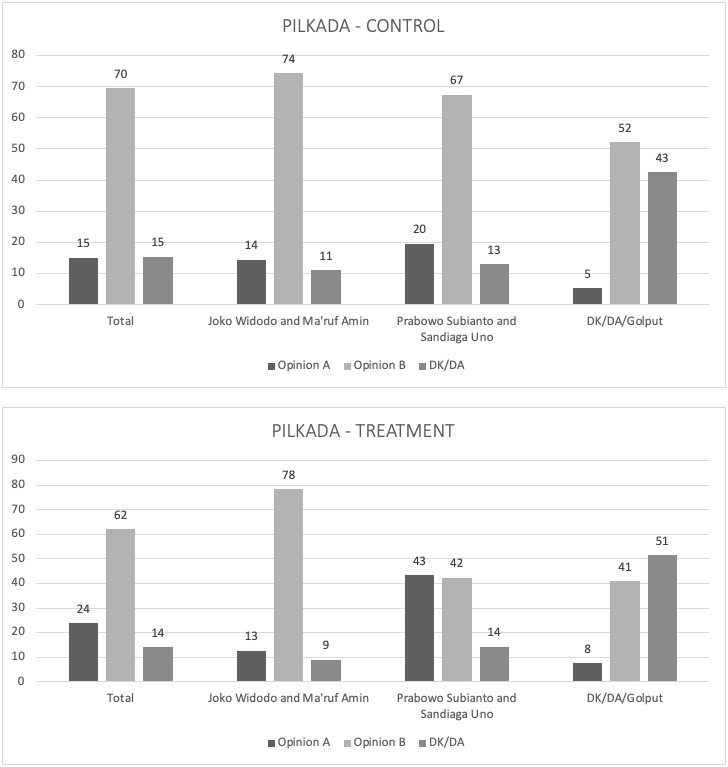

The results are displayed below. (Click to enlarge)

The results from the control group illustrate that, unlike opinion on the Perppu and imports, there is a broad community consensus in favour of direct local elections. Whatever respondents’ presidential choice, a strong majority preferred to keep the system in which Indonesians get to elect their local leaders. This aligns with what most polls have been telling us for many years now about widespread public support for direct elections.

But the treatment group demonstrates that partisan cues change public preferences dramatically. Once told that Prabowo believes local parliaments should be choosing regional heads, not the people, then Prabowo partisans become equally divided on this question. This difference in opinion between Prabowo supporters in the control group and in the treated group is large and statistically significant. The already-large majority of Jokowi supporters that favour direct elections then strengthens even further once exposed to partisan cues—though the difference is not enough to meet the threshold for statistical significance.

The importance of elite cues

These findings have potentially important implications for how we think about the nature and level of partisanship in Indonesia. First, these data, and the results from several other experiments we ran as part of this study, suggest that despite low levels of party ID, and despite the fragmented nature of Indonesia’s patronage-soaked democracy, political figures can elicit strong partisan loyalty. In turn, Indonesians respond to elite cues as much as voters in advanced and established democracies.

Partisanship of this nature tells us that many Indonesians trust in and feel loyalty toward certain political figures. And this might help us to understand why we see such high electoral turnout in Indonesia compared to many other countries.

Second, partisan loyalties in Indonesia produce biases amongst the electorate, and those biases shape and determine voters’ positions on important policy questions—just like in established Western democracies. Prabowo’s sustained anti-import rhetoric, for example, has clearly resonated with his base, such that even without being exposed to partisan cues, Prabowo supporters in our survey were far more opposed to foreign imports than Jokowi voters. Once leader cues are introduced, though, public opinion polarises more.

These partisan loyalties have implications for Indonesian democracy too. Our survey shows that Indonesians’ democratic preferences, specifically their beliefs about the right to organise, and about the efficacy of direct elections, can shift in response to their leaders’ position. Public support for democracy in Indonesia has often been portrayed as a critical defence against illiberal politicians. But our study suggests that, while Indonesians routinely express their commitment to democracy, there is a segment of the population whose support is shallow and changeable, and vulnerable to the anti-democratic appeals of popular leaders with authoritarian designs.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss