It’s on – Malaysia’s Election Commission has announced that the nation will go to the polls on Saturday 19 November.

Knowing the date feels like a relief. For weeks and months now, Malaysians have been steering their way through the usual pre-election fog of media and analyst hyper-speculation about dates, coalitions, and tactics. They have largely responded with pessimism and disenchantment—as they tire of the politicking while they slog through tough economic conditions.

In the weeks to come, parties and candidates will announce what seats they are standing in and which coalitions they will form or join. Trying to the follow the daily play-by-play will likely get complicated and I hear from Australian media sources that their audiences get sick of it. That’s fair enough – an excess of tactical commentary is a serious barrier to informed understandings of regional politics.

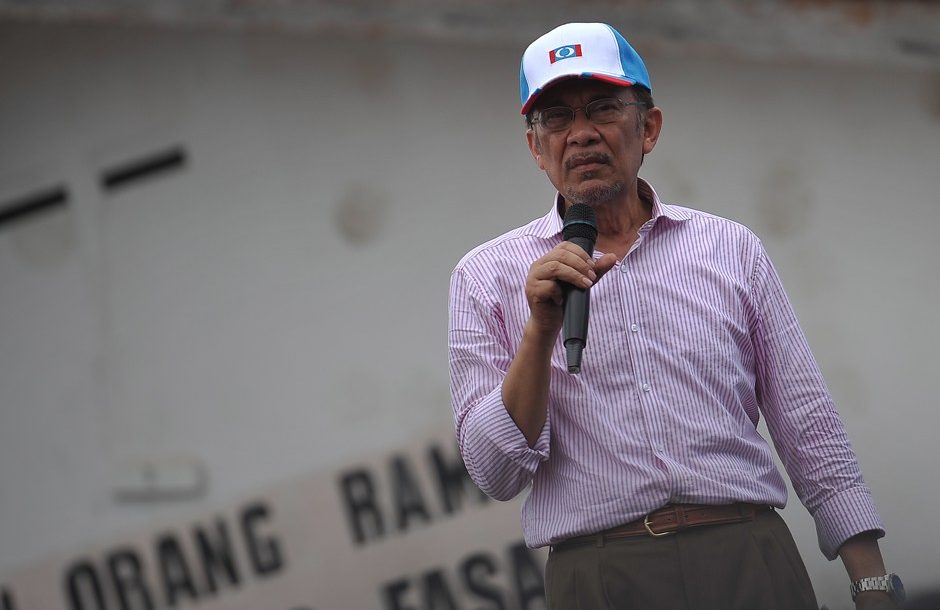

So, to observe some of the deeper stakes involved in this election, look to the actions of one of the key contenders in this campaign—opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim.

If the 178-page book he recently launched is any guide. Anwar is betting that there will be a battle of ideas in this election campaign, despite the government likely hoping that its recent Budget will shore up its own pitch to voters, who it expects to stay home instead of turning out to vote.

In any case, surely the book is too lengthy to be chopped up into small, media-friendly pieces and socialised quickly enough to make an Anwar-led coalition both coherent and competitive?

Called SCRIPT For a Better Malaysia, the book does not purport to be a policy manifesto, but rather a “wholistic vision and policy framework for a viable, dynamic, and inclusive Malaysian future.”

Drawing on decades of Anwar’s thinking as an activist, intellectual, and politician, the book cites influences such as Ungku Aziz, Arjun Appadurai, Syed Hussein Alatas, Zygmunt Bauman, Jomo Kwame Sundaram, Anthony Milner, and Ziauddin Sardar – once Anwar’s education adviser.

The book is organised around several themes matched to the SCRIPT acronym – Sustainability, Care and Compassion, Respect, Innovation, Prosperity, and Trust. It was written in collaboration with The Centre for Postnormal Policy and Futures Studies – the consultancy Sardar now leads and whose focus is to promote “futures literacy,” with a focus on “marginalised peoples and Muslim societies.”

One of the key arguments the book makes is that Malaysians—Muslim and non-Muslim—must come together to imagine radical new futures, now more than ever as these are “postnormal times.”

Sardar, paraphrasing Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, describes these times as an “in-between period where old orthodoxies are dying, new ones have not yet emerged, and nothing really makes sense.”

In the Malaysian context, the Gramscian “morbid symptoms” that make this condition clear include “mismanagement, corruption, cronyism, … divisions, and squabbling.” According to Anwar, Malaysian political leaders who display these symptoms are entirely unfit to address the challenges of an “accelerating, globalised, networked world, steeped in contradictions, complexity, and chaos.”

Anwar’s book has the flavour of a genre of crisis writing popularised by another author it cites: Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Taleb’s Antifragile prescribed not only strength training, including heavy deadlifts; but also, a series of personal and political attitude adjustments as measures to build resilience in what is arguably a new phase of history characterised by endless, rolling crises.

It also echoes a more recent term – “polycrisis,” – recently made famous by economic historian Adam Tooze to describe a situation of multiple crises, “where the whole is even more dangerous than the sum of its parts.”

Accordingly, it speaks of floods, climate change, the pandemic, rural debt, poverty and inequality, disrespect, a closed political culture, and an education system focused on issues like period spot checks and not on fostering qualities such as care, compassion, or innovation. It also raises issues like automation, robots, and, astutely, racist AI – exactly the kind of high-tech innovation a racially striated society like Malaysia could do without.

Malaysia: The New Political Normal, for Now

The promise of the “New Malaysia” that would emerge after the historic 2018 election has been delayed again indefinitely.

It points to the gig economy as a specific source of grief—including for underemployed graduates—along with Malaysia’s low productivity, low wages, and regulatory inertia.

Recognising their resulting crisis fatigue, Anwar’s book speaks directly to voters: “we must not forget that your sacrifice, your perseverance, and your spirit to carry on, when everything was against you, has delivered us through a global pandemic marred in concurrent political and economic crises.”

In terms of offering solutions, Anwar’s discussion under each theme appears to look in two directions. One is towards his history, which dates back to the 1960s, of thinking through the challenges Malaysia has faced as a diverse, yet highly unequal, postcolonial society.

In the 1970s, Anwar was a young Malay rights activist who turned to Islam as a prescription for decolonisation, leading ABIM, an NGO that contributed enormously to the Islamisation of Malaysian politics.

And yet, even as he became a powerful political insider from the 1980s, he seemed to already grasp that no force in Malaysian society could suppress its diversity completely while also improving its social and economic resilience.

This realisation has caused him always to return to questions of how Muslims and non-Muslims could live together in a respectful society and caring economy—themes he rehearsed while building a political opposition after his late 1990s expulsion from the centre of Malaysian state power.

The other direction is towards a future seemingly imagined via Kanban ideation, in a bureaucratic/NGO version of tech start-up culture. Indeed, each theme in the book appears to have been put through a vision-boarding process using markers, Post-it notes, and butcher’s paper, presumably while on retreats with Sardar and his team.

These retreats were apparently interrupted not only by the pandemic but also by the Sheraton Move, which brought down Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan government in 2020. Perhaps as a result, the book reads not so much like an explicit political narrative, but more like the result of a brainstorm session.

It is, after all, a framework and not a manifesto. Anwar’s ideas for creating a culture of social repair in Malaysia are set out in the broadest terms. The book names a vast range of issues that all need addressing, such as energy security, waste collection services, national insurance and investment schemes for emergency and humanitarian relief, student debt relief, and a Court of Protection to rule on welfare matters.

It points to the need for improved farm-to-table systems that pay farmers better while improving Malaysians’ food security. It even raises the idea of awarding social credits for “positive actions.” It also speaks of creating more “humane” economic and financial institutions, along with better social welfare provisions, for an inclusive economic recovery.

Among all these issues, it also speaks of the need for a “polylogue” on finer-grained solutions, in which Malaysians, in all their diversity, can develop not only policy specifics but a variety of languages and culturally relevant idioms in which to debate them.

The idea that Malaysians will take control of SCRIPT’s ideas is an important signal. Observant readers will notice that the book is not a pitch to implement democratic reforms, like the many that were made by and to Anwar’s government before it was rolled and reformists’ hopes were dashed. Rather, it is a pitch to lead Malaysians as they set out together to repair their social fabric.

In this way, the book foreshadows that not only will its ideas be drawn upon in campaign messages rolled out in the weeks to come, but they could also form the basis of a longer-term campaign, including in the states that Pakatan Harapan still controls, in the event that it loses the election. Those states are not holding state elections at the same time as the federal election.

It must be tough still playing the long game in politics at the age of 75, especially when the short-term tactics of election campaigns tend to consume so much political oxygen.

Perhaps Anwar can take consolation from the fact that in Malaysia, politics truly is a long game. His long-term frenemy, former Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, is still in it at nearly 100.

Dr Amrita Malhi’s New Mandala report on Pakatan Harapan’s collapse amid a furore over how to manage race and racism, is available here. Her previous New Mandala articles, including a series of interviews with Mahathir Mohamad, are available here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss