“Will it still be customary for movie-goers to stand for the royal anthem ten years from now?” I wonder, as the familiar ritual compels me to my feet before the start of the feature.

Ten Years Thailand invites four Thai directors to imagine what their country will be like a decade from now. It follows the surprise success of the 2015 Hong Kong film Ten Years, which reflects the pessimism many in the city feel as their “special autonomy” withers away and mainland China steadily exerts its authority. In addition to the Thai release, Taiwanese and Japanese versions are also in production.

The premise of the original Hong Kong film might have given the Thai directors pause for thought in the treatment stage. The narrative popular amongst activists in Hong Kong is—rightly or wrongly—one of a linear decline. They feel that, since the 1997 handover from the British to the People’s Republic of China, rights, freedoms and cultural identity have gradually eroded. A nostalgia for the past intersects with a gloomy present and a fear of the future. All of this was reflected in the five short films comprising the original Ten Years.

But how can Thailand’s past, present and future be imagined? What bleak stories can be told about what Thailand will be like in a decade, when Thais have already lived under nearly five years of military rule? What dystopian horror in 2028 could be worse than 2010, when military snipers shot unarmed protesters in the head, causing their blood and brains to spill out onto Bangkok’s uneven paving stones? What could be worse than the killing, raping and lynching of students in 1976? Or the burning alive of hundreds, if not thousands, of suspected communists in 1972?

Thailand’s troubled history might have forced the directors to dispense with any easy “good-to-bad” narratives and instead opt for stories that are less linear and more experimental than their Hong Kong counterparts—styles which, in any case, put the four Thai directors in their natural element. Rather than simply project into the near future, two of the films in Ten Years Thailand seem to float around in an indeterminate present—nonetheless hinting about the past and the future. The other two take bold leaps to alternative dimensions or galaxies.

Sunset by Aditya Assarat sees a group of soldiers and police pay a surprise visit to Bangkok’s Artist + Run gallery (which recently held an exhibition of political art by satirist ‘Kai Maew’). Surveying the photography on display, they express concern that the portraits of everyday life may cause “conflict and misunderstanding” in society. Of particular concern is a photograph of a rank and file police officer crying in Burger King (ironically, a scene from a Thai film showing a monk crying at his ex-girlfriend’s funeral was censored just last month). Photographs like this might be understood by “foreign educated” artists, say the police, but could give “ordinary people” the wrong idea. As they say this, they gesture towards the Isan-speaking cleaners of the gallery.

Song of the City by Apichatpong Weerasethakul is set entirely in Ratchadanussorn Park in Khon Kaen, where the director was born. The sights and sounds of construction work suggest a province (and region) undergoing change. Apichatpong captures both the mundanity and charm of provincial life with his signature familiarity and confidence: people chat about nothing in particular, a man breaks into a morlam singing performance, another man sleeps lazily in a mosquito net while a fan keeps his back cool. All of this goes on under the sinister gaze of Field Marshall Sarit Thanarat, the infamous dictator, whose statue dominates the park. Off-camera, we hear some kind of military parade taking place, reminding us that the army are never far away. At one point, a man extols the benefits of a “good sleep machine” to a woman, who tries the contraption and falls into a peaceful, deep sleep.

Catopia by Wisit Sasanatieng imagines a world in which cat-like creatures have practically eliminated humans. Perhaps only one man has managed to survive by hiding amongst the cats, pretending to be one of them. When the cats suspect they have found a human, an orgy of violence ensues and the human is stoned by a hissing mob of the blood-thirsty cats. Some of the tropes in this segment are well-worn sci-fi fare but strong performances, direction and special effects more than compensate. The allusions to groupthink and darker periods in Thai history are obvious.

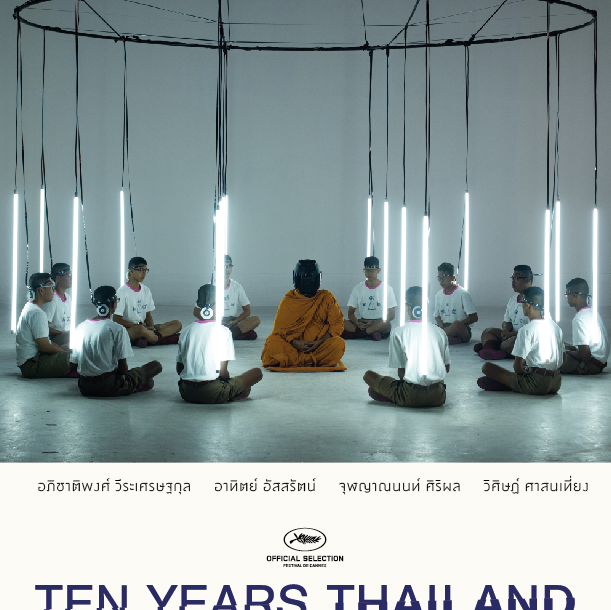

Planetarium by Chulayarnnon Siriphol is my personal favourite of the four. The trippy, technicolored piece pulses with a funky synth-pop soundtrack as it reveals the inner-workings of The New Youth, a youth-wing of the state who are responsible for locating and “correcting” citizens who deviate from the norm. The youths—who wear scout uniforms—have their heads shaved into crew cuts, undergo training and participate in strange, cult-like dances around a glowing pyramid. It’s quirky, dazzling to watch and loaded with social commentary.

Ten Years Thailand comprises four very strong short films from established and up-and-coming directors. They are stylistically different but compliment each other well as an anthology. The stories don’t so much predict Thailand’s future but rather—like all good dystopian fiction—tell us about its past and present. The film opens with a quote from George Orwell’s 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future”. Artistic works like Ten Years Thailand help take back control of the past (and present)—the only way Thais might one day be able to wrest back control of their future.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss