The Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) has been labeled a terrorist organisation. It has caused a number of deaths—local civilian as well as security personnel. It is to be condemned and rooted out—no doubt about that at all. Indeed, since over two years ago, think tanks and diplomats in neighbouring countries have warned me personally about Islamist terrorist groups making their advent in Myanmar and I had passed this information on. The violence erupted as these friends had foretold, and we are now seeing the nature and the extent of the Myanmar state’s response. At this point we need to deeply consider one fundamental question: is ARSA and its attacks the cause or the consequence?

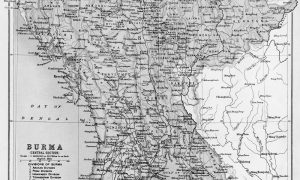

The Rohingya issue has a long provenance, but beginning from the first military junta period (also known as the Burma Socialist Programme Party regime) that community began to be regarded as a problem from at least the 1970s. Immigration operations were carried out in the northern Rakhine border townships of Buthidaung and Maungdaw. At least on two occasions, hundreds of thousands of Muslims (mostly Rohingya) fled into neighbouring Bangladesh. Official negotiations had to be held and most of those who had fled were taken back.

The Myanmar government’s next response was to bottle up the Rohingya in those and adjacent townships, in the process stripping them of many basic rights. That region became a ghetto or quarantined area, and the situation festered for decades. The communal violence that erupted in 2012 started in another area of Rakhine state, and quickly spread to central Myanmar and also to north Rakhine. There were burnings and counter-burnings of homes and entire villages, in addition to other atrocities. As a result many Muslim communities were moved into IDP camps ‘for their own safety’, these became in actuality 21st century concentration camps. Rakhine Buddhists have been displaced too, and there are a number of Buddhists from Bangladesh who have sought refuge in Rakhine.

It is well known by now that herding people into confinement (by whatever name it goes) and depriving them of their rights is a surefire way to breed violence, crime and militancy. This policy is as misguided and ineffective as it is inhumane. Continuing it and expecting people to be docile is the height of delusion.

The present crisis, with 400,000 Rohingyas having to take shelter in Bangladesh, is still in its early stages. The Office of the State Counsellor, no less, has announced that 432 have lost their lives. Of the people who have fled, only those who can show ‘proof’ will be allowed back. The state counselor herself will be making a speech to the nation (in English) on Tuesday 19 September—in part to make up for not going to the UN General Assembly meeting, I might add. Here, I would like to say that simply addressing the nation, and all the accompanying pious rhetoric, cannot make up for sheer incompetence in policy and on the ground responses.

Those in positions of authority will do their best to wriggle out of this crisis with bluster, spin and lies. Decent and well-intentioned people within the country and the world over must hold them accountable and task them with effecting urgently-needed changes. At the risk of sounding theatrical, if this opportunity is passed over and lost, the forces of darkness in Myanmar shall win again. Yes, a number of geopolitical assessments have been penned, and I dare say there are people in many foreign capitals making their calculations. But at this point I must stress that human lives matter more than geopolitics, a warning not only for the Rohingya but for all the people in Myanmar as well. If the dark forces are emboldened, other ethnicities and communities will certainly experience the edge of their hand. This occurred in the mid-1960s, when Ne Win gained a measure of popularity by chasing Indians, Pakistanis and Chinese out of then Burma, after nationalising their business and property. Two decades later, hundreds of Bamar protesters had to die in the streets to bring his regime down.

Donald Trump notwithstanding, many developed countries are embracing diversity, multiculturalism and the value of immigrants. Myanmar does not have to be rich or developed to understand and accept this fundamental, undeniable historical fact.

…………………………

Khin Zaw Win is the Director of the Tampadipa Institute, working on policy advocacy and capacity building since 2006. His current engagement includes communal issues, nationalism and international relations. He is also an honorary advisor at the Myanmar Institute for Strategic and International Studies, the Foreign Ministry’s think tank. He served under the Department of Health, Myanmar, and the Ministry of Health, Sabah, Malaysia and did the Masters in Public Policy programme at the National University of Singapore. He has held a fellowship with the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (New York office) and was also a UK FCO Chevening Fellow at the University of Birmingham. He was also a prisoner of conscience in Myanmar for “seditious writings” and human rights work from 1994 –2005.

Header photo via Flickr user Dany13, used under Creative Commons.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss