In line with Bali’s image as a tourist icon, visitors to the Bali: Welcome to Paradise exhibition at the Museum Volkenkunde, an ethnographic museum in Leiden, are greeted by stereotypical images of sand and sun in the form of two lounges beneath a beach umbrella. The floor is a creamy yellow, suggesting pristine sandy beaches. An image of the Tanah Lot temple, recognisably perched on its black rocky outcrop, is projected behind the lounges. A lone surfer stands facing the temple. Superimposed on the image, in bright yellow, is the exhibition title. On the day I visited, a wintry Leiden afternoon, some museumgoers reacted excitedly to this playful opening display. They took selfies and photographs of their friends with the display.

Tanah Lot. Source: Unsplash photos.

Yet, of course, the image of Tanah Lot carries another meaning. When a new international hotel was planned there in 1997, sections of the Balinese community and activists had protested that the development was disrespectful of the holy site and would create environmental problems. In 2017, the Pan Pacific Nirwana Resort in Tanah Lot shut down to make way for a refurbishment and a new management, Indonesia’s MNC group in conjunction with the United States president, Donald Trump’s company, the Trump Organization. The opening scene, evoking a beach paradise, evokes this dual meaning of Tanah Lot as simultaneously a symbol of environmental battles and a holiday resort.

From the sea, sand and sun image, visitors are introduced to the idea that tourism has had a dramatic impact on the island and its people. In the first exhibition room, rice, agriculture and water are discussed. A glass case displayed manual ploughing and harvesting tools, as well as three representations of Dewi Sri, the Goddess of Rice, made out of woven grasses and leaves. A large photograph of Bali’s famed terraced ricefields at sunset serves as wallpaper on one wall of this room, creating an immersive atmosphere by its size. Using text boards, the exhibition informed the visitor that water and rice have remained important in Balinese life despite the pressure on them from tourism. Three graphs show population growth, tourism numbers (with the Netherlands making up 2 per cent of total international tourist numbers) and the number of hotels. As if to illustrate these graphs, in the same room, a large photograph of a Western resort-style, multistorey hotel, built around a pool shaded by frangipani trees, wallpaper the wall opposite the image of the terraced rice field. The curator seemed to suggest that the hotel and the ricefield were diametrically opposed to one another.

However, the inclusion of Balinese voices in the short films played on a loop in the room leavens the stark contrast that the wallpapers seem to represent. In one film, a room attendant described her daily life as Balinese woman juggling work in a large hotel with family life and her religious ritual obligations. Asked about tourism, she replied that sometimes the tourist just did whatever he or she liked with little regard for the place they were visiting. On the opposite wall, Balinese artist Made Bayak discusses the water distribution or subak system and how tourism has put an enormous pressure on Bali’s water resources. The inclusion of these voices suggested to the visitor that the Balinese were well aware and reflective about tourism’s impact on their society.

Following this introduction, in the passageway, the visitor is confronted with the photograph of a traffic jam of motorcycles accompanied by text titled ‘The other side of paradise’. On the opposite wall was a large image of serious plastic pollution on a Balinese beach. Using interactive iPads and old style telephone receivers, visitors can listen to the different points of view of those who had dealt with Bali’s plastic and rubbish problems, such as surfers and young people volunteering with local non-government organisations.

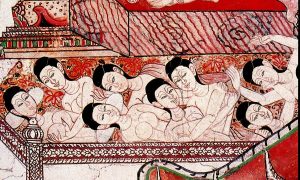

The next section of the exhibition is simply titled ‘Oleh-oleh Bali (Balinese gifts): Fruits, Offers and Souvenirs’, featuring woven baskets and offering items, textiles, and sandals. This section discusses the Sukawati Market where Balinese purchase the goods they needed for Hindu offerings and tourists bargain for mementos of a tropical holiday. Short videos feature the voices of market traders, offering-makers, and a man who sells packaging products, such as plastic wraps and waxed paper, who could only hope that consumers of his product disposed of them appropriately. Flowing from the focus on offerings, the exhibition then displays objects, text and videos in an adjacent room on Hindu ceremonies for different phases of life, such as tooth-filing, marriage and death.

Next door, the exhibition takes a sombre turn. Under the subheading of ‘Colonialism and tourism’, the room’s displays and texts discuss the Dutch colonisation of Bali, when by 1908 it had subjugated the four major kingdoms of Buleleng, Badung, Tabanan and Klungkung. Items that the Dutch looted from Klungkung were distributed between three Dutch museums, including the Volkenkunde. Carved wooden doors shown in this exhibition were, for example, looted from the ruined Badung Palace, as were a golden bowl and a dancer’s vest taken from Klungkung. In these Dutch attacks, Balinese people were killed or committed ritual suicide (puputan).

Doors to the ruined palace of Badung, Denpasar; wood, circa 1800-1850. Collection of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National Museum of World Cultures). Photo: Ben Grishaaver

Dancer’s vest, captured at Klunkung; velvet, gold, 1850-1900. Collection of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National Museum of World Cultures).

Golden offering bowl, captured at Klunkung; gold, pre-1908. Collection of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National Museum of World Cultures).

Dutch administrators then ‘created the image of Bali as a paradise island,’ the exhibition’s curator argues, in order ‘for the Netherlands and the rest of the world’ to forget the violent colonisation campaigns. In 1914, the Dutch East Indies published the first tourist brochure that heavily emphasised Bali’s spectacular sights and peaceful nature. Tourism grew, and by the 1930s, many Western artists, such as Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet visited Bali and made it their home. This highly crafted image of paradise, constructed out of the ashes of Bali’s sacking by the Dutch, continues to underpin its booming tourist market today.

The white surfers’ beaches of Bali. Source: Museum Volkenkunde.

This exhibition provides a sympathetic portrayal of Bali as a place that has proven resilient to dramatic, and at times violent, change. Balinese artists continue to critique, as well as embrace, tourism through their art. One of this exhibition’s aims seemed to be to create more discerning tourists, with around 100,000 tourists arriving there directly from the Netherlands in 2017, according to Bali’s provincial statistical bureau. The number of Dutch tourists is likely to be higher when taking into account those who arrived in Bali via other countries. The exhibition relies on three main components: projections on the wall consisting of photographs or short videos featuring Balinese people in recent times speaking about their lives and their way of life; the precious antique collections of Dutch museums including items that were looted from the Balinese courts; and everyday objects including arts and crafts marketed to tourists. A phone app related to the exhibition can also be purchased. Although it is a relatively small exhibition, it nevertheless packs a punch and is at once stimulating and enlightening. It engenders great respect for the Balinese people and the challenges they confront in living in a major global tourist destination.

Sacrificial altar in the shape of a mythical animal, Bali; wood, around 1900. Collection of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National Museum of World Cultures).

Bali: Welcome to Paradise is showing at the Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, until 26 May 2019. For more information visit: https://www.volkenkunde.nl/nl/bali

Follow the conversation on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/groups/1173439272675439/) or Twitter (https://twitter.com/seasiapasts?lang=en)!

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss