“The peace table is now wide open for everybody,” declared Presidential Peace Adviser Jesus Dureza to mark the National Peace Consciousness Month in the Philippines.

“This table is not only for the Muslims, for the New People’s Army, for the indigenous peoples, but for all Filipinos,” he added.

While Dureza reserves their seat, the New People’s Army (NPA) shows no signs of returning to the table. Rejecting President Rodrigo Duterte’s call for localised talks, the NPA remains a growing threat to national security, especially in Mindanao.

As of June 2018, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) estimates the presence of approximately 3,900 NPA rebels nationwide. The Eastern Mindanao Command reports 50% of the NPA’s strength resides in within its area of operations. Whereas the AFP is confident in its ability to degrade and inevitably defeat the NPA, the level of NPA violence in Mindanao has increased since the election of Duterte.

Source: Angelica Mangahas and Luke Lischin, Political Violence in the Southern Philippines Dataset

Of the 1,103 incidents recorded from January 2017 to July 2018 in the Political Violence in the Southern Philippines Dataset, the NPA was involved in 425 or just over one quarter of all incidents. This dataset is based on the coding of open source-materials including periodicals, official press releases, and academic/humanitarian reporting on episodes of political violence occurring within the administrative boundaries of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.

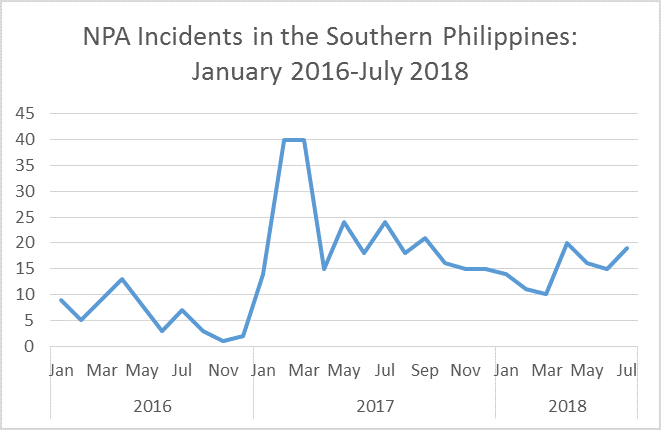

NPA violence dogged the final months of Benigno Aquino III’s presidency before giving way to a “honeymoon period” after Duterte’s election, which led to a formal ceasefire agreement in August 2016. The ceasefire effectively reduced violence to negligible levels, but could not produce lasting peace in the absence of a negotiated political settlement. With the breakdown of negotiations and tensions in the field, the NPA formally ended the ceasefire on 30 January 2017 with a heightened series of offensives through April 2017. After dropping off in April 2017, the number of NPA incidents picked up again from May through September 2017 when Duterte declared Martial Law in Mindanao due to the Siege of Marawi. This explicitly motivated the NPA to escalate its operations, which in turn led the Duterte administration to cancel the anticipated fifth round of peace talks.

The Mamasapano clash, memories of violence, and the politics of Muslim belonging in the Philippines

On the Mamasapano clash and the exclusionary narratives it reinforced.

Across all incidents the NPA was responsible for killing 168 soldiers, police officers, and civilians, while wounding an additional 266. Casualties on the side of security forces peaked at 67 in July 2017, when a short series of ambushes in Bukidnon and Compostela Valley resulted in relatively heavy losses for the AFP. By August 2017 through March 2018 casualties averaged 10 per month, and then increased to 16 casualties per month from April 2018 to July 2018, showing a clear increase in the intensity as well as the frequency of NPA incidents.

Meanwhile the NPA sustained 185 fatalities and 109 injuries within their own ranks. 20% of the fatalities and almost 25% of the casualties were sustained during the March 2017 post-ceasefire hostilities. This marks the single biggest period of losses for the group. Otherwise, NPA fatalities and injuries remained low in total but persistent over time, averaging about 3 fatalities and 7 injuries per month. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the casualties sustained by the NPA as well as the surrenders of rebels flaunted by the government have not visibly reduced levels of NPA violence over time.

Source: Angelica Mangahas and Luke Lischin, Political Violence in the Southern Philippines Dataset

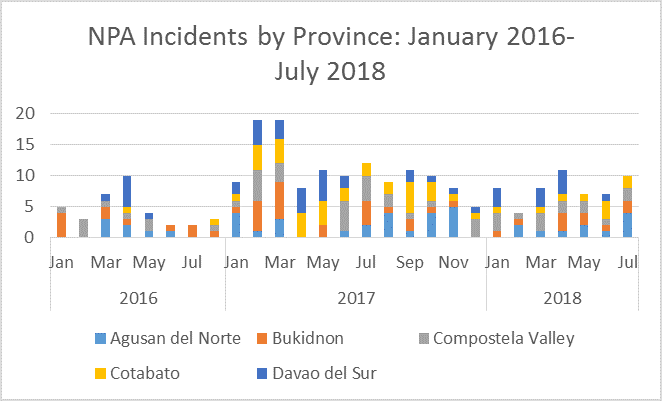

Fluctuations in the numbers of NPA incidents were also observed geographically. From January 2016 to July 2018, 23 provinces in the Southern Philippines experienced NPA incidents, during which time only Compostela Valley (48), Agusan del Norte (44), Bukidnon (44), Cotabato (44), and Davao del Sur (43) experienced more than 40 incidents, accounting for roughly 61% of total injuries and 50% of total fatalities on all sides.

Of these provinces, Cotabato transformed from one of the least violent provinces in all of Mindanao in 2016, to the most violent in 2017. Unlike NPA incidents in Compostela Valley, Bukidnon, and Davao del Sur, the overwhelming majority of NPA violence in Cotabato consisted of armed assaults against security forces where the NPA was on the offensive. In Agusan del Norte security forces also experienced relatively high levels of NPA attacks, especially in 2017, but these did not escalate as dramatically those in Cotabato.

Source: Angelica Mangahas and Luke Lischin, Political Violence in the Southern Philippines Dataset

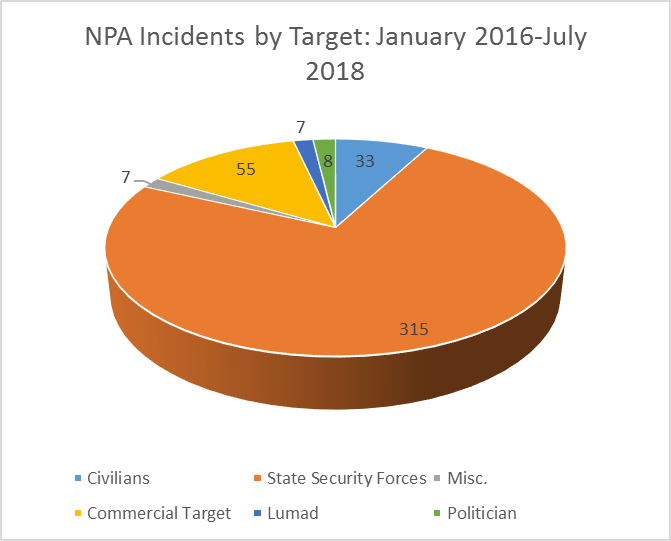

Beyond just Cotabato and Agusan del Norte, the NPA overwhelmingly favoured security forces as their target. Although the military often dismisses the NPA as bandits, 74% of all NPA incidents engaged state security forces. Only 13% of NPA incidents targeted obvious commercial sites, such as company vehicles, plantations, mines, and offices. Over 40% of incidents directed at commercial targets occurred in the provinces of Bukidnon, Davao del Sur, and Agusan del Norte. Lumads, politicians, regular civilians, and other miscellaneous targets were victimised in the remaining 16% of incidents. Some of these incidents may have also entailed financial motivations, but the abduction, injury, or murder of these persons were undoubtedly politically motivated.

With 5 months yet to be coded in the dataset, 2018 has already surpassed 2016 in terms of the average number of incidents and casualties per month. It is likely that it will match or even surpass 2017 by the same measures. As NPA violence grows worse, it becomes difficult to envision a return to the negotiating table given the lack of effective military solutions or political incentives. In the meantime, the Duterte administration and analysts like Rommel Banlaoi insist Martial Law will keep violence from the NPA and other groups under control, but so far this blank-cheque approach to counterinsurgency has yet to pay real dividends.

Alternatively, localised peace talks and greater regional autonomy via federalism are non-military solutions promoted by the Duterte administration. The prospect of devolved governance has achieved preliminary but positive results in Mindanao with the Bangsamoro Organic Law, and may hold promise for other conflict-affected regions, including proposed Autonomous Region for the Cordillera.

Nevertheless, the NPA considers localised talks to be “a classic divide and rule tactic” and is equally suspicious of federalism, making the path to peace through governance an uphill battle no matter how it is waged.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss