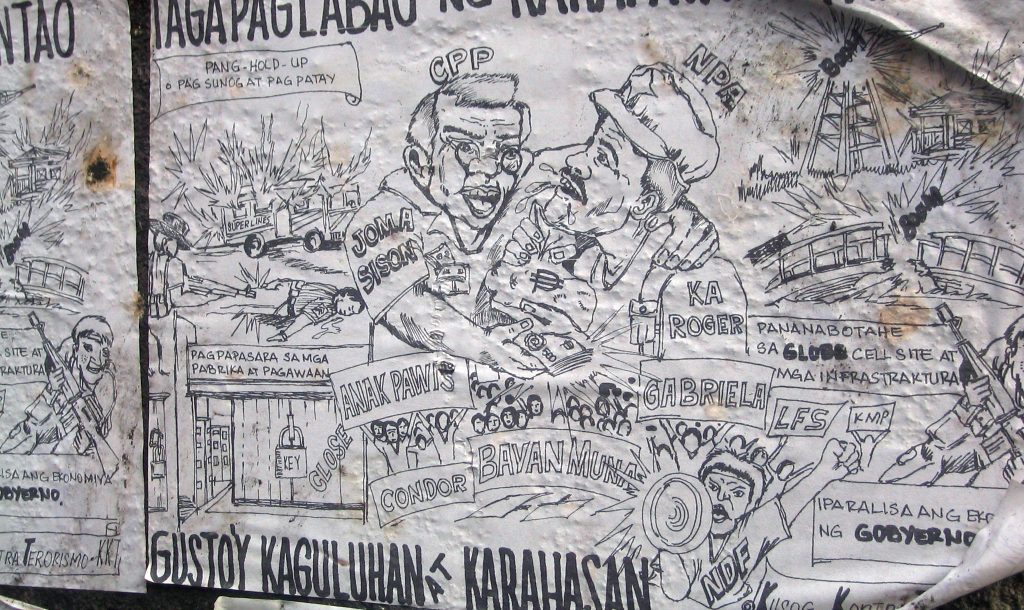

When the US declared a “war on terror” after 9/11, states around the World began reconceptualising long standing insurgent groups as “terrorists”, including those with no record of organising random mass casualty attacks on civilians. The US designated the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its armed wing, the New People’s Army (NPA) as a terrorist organisation in 2002. The European Union (EU) and New Zealand followed suit, while Australia implemented financial sanctions but it has not designated the movement as a terrorist organisation.

Filipino legal scholar, Jayson Lamchek argues these designations emboldened the Philippine authorities to embark on a particularly abusive counterinsurgency campaign against the CPP/NPA.

The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (2001-2010) began presenting the wider national democratic left and human rights activists as a “terrorist network” supporting the CPP/NPA. A campaign of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances of leftist activists by the AFP during the Arroyo Administration ensued. Killings continued under the Aquino Administration (2010-2016), albeit at a reduced intensity.

Upon election in 2016, President Rodrigo Duterte initially promised a peaceful end to the insurgency through restarting peace negotiations with the communist movement. However, when the negotiations broke down in 2017, the Duterte Administration launched an “all out war” against the CPP/NPA, reminiscent of its infamous “war on drugs”. The following year, Duterte even urged the AFP to replicate General Suharto’s 1965-66 mass murder of accused leftists.

In June 2020, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet presented a report on the current human rights situation in the Philippines noting with alarm how the Philippine authorities now commonly equate peaceful dissent with support for the CPP/NPA insurgency. Government officials and the AFP frequently vilify human rights lawyers, journalists, trade unionists and other critics of government policy as CPP/NPA supporters, a practice known locally as “red tagging”. Red-tagged individuals are subsequently harassed by the authorities or even subject to extrajudicial killings, as was the fate of the prominent human rights lawyer Benjamin Ramos Jr in 2018.

Following Bachelet’s report states, supranational organisations such as the EU and non-governmental organisations were given a chance to respond to its contents during an “interactive dialogue” session. The US no longer participates in the UNHRC but the other jurisdictions the EU, Australia and New Zealand, all voiced their concerns regarding extrajudicial killings and the vilification of dissenters in the Philippines.

Unfortunately, these jurisdictions’ terrorist designations of the CPP/NPA undermine this otherwise progressive stance, giving the Philippine authorities an impression their vilification of opposition enjoys international support.

Intolerant leaders for intolerant citizens: illiberal values in the Philippines

Survey data suggest Dutertismo isn't necessarily out of line with popular values.

Posts published on the state-run Philippine News Agency website red-tagging opposition figures and human rights advocates almost always include a sentence listing the jurisdictions* which have designated the CPP/NPA. A recent example saw an 83-year-old nun branded a “communist” after she had the audacity to condemn the cyber-libel conviction of journalist and Rappler CEO Maria Ressa, a prosecution many consider politically motivated. The foreign designations have also been cited to support military/police raids on the offices of activist groups and the vilification of mainstream liberal opposition electoral candidates.

Not only do the US, EU, Australian and New Zealand designations encourage abuses by the Philippine state, they also prevent these jurisdictions from playing any meaningful role in efforts to end the CPP/NPA insurgency via peaceful means. Unlike Norway, which has not designated the CPP/NPA, these jurisdictions cannot act as neutral third-party facilitators in peace talks between the communist movement and the Philippine government.

Governments often argue their terrorist designations of armed groups play an important symbolic role, signifying the utmost condemnation of politically motivated violence. However, in the case of the CPP/NPA, foreign jurisdictions’ designations have encouraged further political violence and undermined prospects for a peaceful resolution of the conflict. The designations have emboldened the Philippine government to engage in attacks on peaceful opposition. This reinforces the CPP/NPA’s argument that armed struggle is necessary to change Philippine society, leading to an endless cycle of violence.

If the US, EU, Australia and New Zealand are serious about supporting human rights in the Philippines, they must revoke their terrorist designations of the CPP/NPA and unequivocally support a just and peaceful resolution of the conflict.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss