It’s commonly argued that populism threatens democracies in ASEAN and elsewhere, but this allows the threat of unaccountable elites to slip under our collective radar. This is unfortunate, because elites could threaten ASEAN democracies more than populists.

Democracies are more than just elections (which ASEAN has lots of); they also include checks and balances like the rule of law, separation of powers, and independent media. These checks and balances are subject to domestic, regional and international oversight and pressure, which can—and have—increased their quality over time.

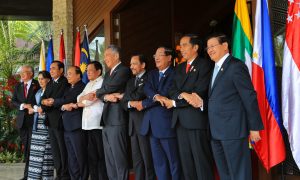

Various ASEAN leaders, from Shinawatra and Hun Sen to Duterte and Jokowi, have been labelled populist, rightly or wrongly. In political science, one can argue that politicians in representative democracies must pander to the wishes of the people (i.e. be a populist), so their recent rise could be a cyclical feature of democracy’s historical arc.

Today’s Southeast Asian states have many categories of elites, with elected politicians being the most visible. However, other groups of elites such as commercial titans, the very rich, academics, aristocrats in feudal structures or professionals such as lawyers or management consultants all exercise power or influence, albeit more invisibly. To place this in context, we have the military elite in Myanmar and the religious elite in Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. “Social elites” is a good umbrella term for this heterogeneity.

Social elites interact with political elites for many reasons: technical or strategic advice, networks, campaign financing, or even lobbying. Often, the political elites are the social elites through dual roles or a revolving door, most recently in Indonesia with a tech CEO being appointed Minister. All this is legitimate, although the unfortunate reality of corruption immediately highlights the first challenge with these interactions.

The Threat of Elite Capture

Elite capture happens when social elites inappropriately enter the government’s policy process. Like every citizen, they have every right to participate in the policy process. However, they often play a disproportionately larger role due to intimate access, opportunities to propose or influence policies, campaign financing, or simple conflicts of interest.

Getting the rich or smart to advise governments can be helpful, but it is also a double-edged sword. In democracies, political elites are held to account by built-in checks and balances. None of these transparency or accountability tools affect social elites; often, we don’t even know who the elites are.

In the partly-free democracies of Southeast Asia, the decisions of governments can be more easily influenced (or captured, subverted, hijacked, or whichever term one prefers) by unaccountable elites. This is dangerous to democracy.

The rise of Duterte and Bolsonaro: creeping authoritarianism and criminal populism

In both countries, ugly populist politics is a direct result of legitimate concerns about crime and corruption.

Populism threatens democracy for different reasons. Firstly, it adopts a form of identity politics, which borders on racism, is poisonous for human rights and may result in conflict. Secondly, populism tramples over minority rights by largely appealing to the majority. Thirdly, populism may promise popular (but irresponsible) policies just to win elections without considering any long-term impact. These real dangers should not be underestimated.

Elite Capture is a Greater Threat

Compared to populism, however, elite capture is more threatening to Southeast Asian democracies. First, elite capture is nearly invisible at all times, whereas populism is out in the open. Neither politicians nor social elites are incentivised to publicise their interactions. Society is also handicapped due to the media’s inability to scrutinise interactions that can be reasonably labelled as private.

This handicap is more severe in ASEAN, with its relatively low press freedom. Even if there is effective scrutiny, it is difficult to isolate the effects of one social elite from the politicians’ original positions, or from another stakeholders’ advice. It would also be unfair to automatically mark all interactions as illegitimate. All these limitations keep elite capture invisible or make its effects difficult to pinpoint.

In contrast, populism’s threat is visible; its positions and philosophies can be attacked publicly. It has a name and a face, with political parties and leaders vying for attention in the public domain. Populism must continually subject itself to domestic, ASEAN and international scrutiny. In elite capture, a single domestic society cannot even accurately identify who to counter, much less counter them effectively without their ASEAN or international partners.

Second, elites are not subject to regular elections like populists are. To enter into power, populists must first get elected. While their promises could be intrinsically popular and therefore receive strong public support, other political parties, the Election Commissions, the media and citizens can challenge them. Populists might not even win. Even if they win, one can argue that democracy has won because the vox populi has decided. At regular intervals, populists can also be thrown out of office.

None of this happens in elite capture, because no one ever votes for advisers to the President in the first instance. Even if we are unhappy with the performance of the elites (with a huge assumption that we can even see whose performance to be unhappy with), we cannot vote them out in the next election.

Third, populists—but not elites—are subject to checks and balances while in power. The executive power of populists is constrained by various institutions like the opposition, judiciary, legislature, media, civil society, citizens and international community, all of which can shut or slow them down. None of these institutions exist to oppose elite capture.

The very nature of elite capture seeks to hide not only their existence, but also their impact. Our democracies have not yet consciously built structures or institutions to directly counteract their influence. Existing checks and balances were conceptualised and built over time to counteract demagogues, populists and dictators. They do not have the structure, subtlety and skills to counteract elites who operate indirectly and more in the shadows.

Fourth, elites foster inter-generational inequality, while populists cannot. The policies, changes or regulations that elites want for themselves often coincide with what is best for their heirs or estates. This desire for legacies manifests itself through actions to shape society and systems in ways that benefit their children the most.

This is evident when elites support efforts to eliminate or reduce inheritance taxes or reduce taxation and regulation in general. Quoting individual responsibility, elites have advocated for policies that encourage the state to leave them and their interests alone. While we can treat their justifications neutrally, we cannot treat the consequences with indifference.

In contrast, populism does not have inter-generational inequality built into its credo. Indeed, populism is based on destroying inter-generational inequality. As they must repeatedly bring their anti-inequality case to the electorate, they cannot foster such inequality even if they wanted to.

Fifth, we cannot exercise any nuclear option of forcibly removing elites. Rightly or wrongly, Southeast Asia has removed politicians through protest before, notably Marcos in 1986, General Ne Win in 1988, and Suharto in 1998. Short of street protests and elections, we can legitimately remove populists from power through impeachments, votes of no confidence, or hung parliaments triggering fresh elections. These are all theoretically prescribed in the constitutions and laws of most Southeast Asian countries.

Our democracy also prescribes libel, slander and hate speech laws to constrain irresponsible individuals. Elites and populists alike are covered by these laws, but elites are not the ones shouting from the parapets.

None of these nuclear options are available to remove elites, even if we all wanted it. The reasons are simple: we simply cannot identify who to protest against. Even assuming it is politically acceptable to target “the elite” as an amorphous entity, it is not fair, or just, to tar all elites with the same brush.

Indeed, a society will find it hard to criminalise influence. If we do, then the slippery slope requires elected politicians to not have any family, friends or mentors who could influence them. Even if tools exist to remove elites, it’s impossible to distinguish between offering a reasonable solicited opinion and inappropriately influencing policy.

In humanity’s two million years of existence, we have only had democracy for 70 years. While populism can be dangerous, it is out in the open and can be negated by right-minded people and institutions. Elites on the other hand, can lurk in the shadows and cast their influence without being visible or accountable. When designing Democracy 2.0 in ASEAN, we must consider the invisible threat of elite capture and build new tools to fight it.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss