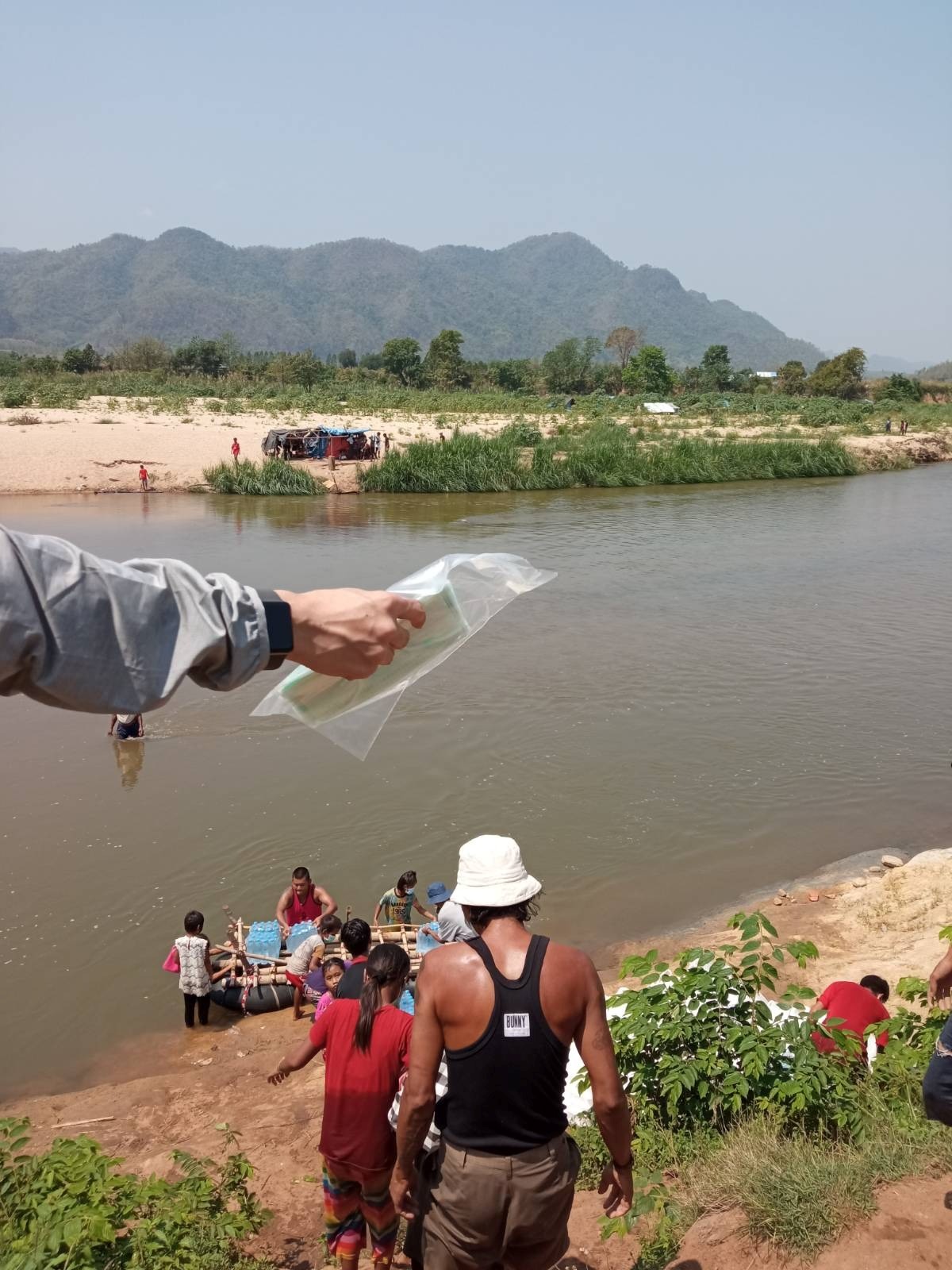

In the cold and dark winter nights, refugees sleep beside the Moei river with no shelter or blankets. Their only resources are donations from regional civil society organisations (CSOs): Myanmar migrant-based community-based organisations (CBOs) in Thailand, Karen region-based CSOs and some Thailand CSOs. Thailand CSOs are sanctioned by the Royal Thai Army, and cooperate with Myanmar’s revolutionary forces such as the KNLA, People’s Defense Force (PDF), and select forces within the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA). The international community, on the other hand, has had no concrete plan to help Myanmar refugees and residents struggling with the effects of Tatmadaw attacks in southern Myanmar.

As conflict broke out between the Myanmar Tatmadaw (military) and Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) forces in “peace township” Lay Kay Kaw in December 15, 2021, serious artillery shootings and air strikes by the Tatmadaw resulted in thousands fleeing to Thailand. This conflict was only one of many effects of the ongoing armed conflict since the Myanmar coup of February 1, 2021.

What the international aid community and governments urgently need to push now is cooperation between the Thai government and ASEAN to accept new refugees in Thailand, to ensure cross-border humanitarian assistance for IDPs on the Thailand-Myanmar border. This can be achieved by cooperating with effective third sectors actors on the ground to distribute aid for those in need. In addition, Myanmar refugee and migrant-focused CSOs such as border-based charities, Myanmar migrant workers associations, and ethnic region-based CSOs must be allowed to freely operate in the border regions.

Migrants on the Thai border lining up for supplies. Photo by Maung Oak Aww.

In southeast and southern Myanmar, the KNLA, the Karen National Defense Organization (KNDO) (the armed wings of the Karen National Union) and the Karenni Army (KA) (the armed wing of the Karenni National Progressive Party), are giving thousands of urban Burmese military training and mobilising the People’s Defense Forces (PDFs), Karenni Nationalities Defense Forces (KNDFs) and Burma People’s Liberation Army (BPLA). These two ethnic armed organisations (EAOs) control areas which are adjacent to the Thailand border, an area currently under siege by Tatmadaw offensives. Populations in these areas are facing the high risk of crimes against humanity. These offensives will likely increase in the future, resulting in further displacement as the number of refugees to Thailand increase.

Refugees fleeing armed conflict need to have safe refuge in areas far from the Tatmadaw’s air strikes and artillery; they should not be asked to return to dangerous zones as previous refugees have been forced to. After the airstrikes on March 27, 2021, residents of Mutraw (Papun) district fled to the Thai-Myanmar border, but were turned around by Thai border authorities. Similarly, refugees fleeing a Tatmadaw invasion of Lay Kay Kaw areas were turned back to Myanmar.

“We have been living between these two riverbanks for more than two months. When fighting closes in on the Myanmar side, we cross the Moei river and stay on the Thai side. We are asked to return to the Myanmar side when the artillery shelling stops,” a resident of Lay Kaw Kaw staying in Moei riverbank, shared with me.

IDPs on the Myanmar side of the Moei riverbank. Photo by Maung Oak Aww.

Recent visits by the United Nations (UN) special envoy to Thailand have appealed to Prayuth Chan-Ocha, the Thai Prime Minister to provide assistance to Myanmar refugees, IDPs, and the restoration of democracy in Myanmar. The two-day visit by Washington’s senior officials in the second week of October, 2021 also called for Thailand to ensure cross-border life-saving assistance along the Myanmar border. But Bangkok has no formal policy for long-term Myanmar refugees on their border.

A temporary shelter for refugees in Thailand. Photo by Maung Oak Aww

However, as the Moso massacre in Karenni state demonstrates, provision of cross-border lifesaving assistance is not possible while the Tatmadaw continues to target civilian populations with air strikes and artillery shelling. The Tatmadaw has even cut off food and medical supplies to their operation areas.

It is imperative that the UN, US, ASEAN and neighboring member states like Thailand ensure the security of aid routes from CBOs and CSOs along the Thai-Myanmar border; these plans must include new concrete plans to aid refugees within Thailand’s borders. Yet, at the time of writing, Thailand is drafting more restrictive NGO law, which is bound to affect the humanitarian assistance available at the border.

The main concern of activists and revolutionaries within the Myanmar community so far has been the effect of international legitimacy on the junta regime’s culture of impunity; many fear that international recognition will give the military free rein to continue the perpetration of serious war crimes, kleptocracy, and the oppression of people in Myanmar.

International aid agencies in Myanmar who have tried to engage with the junta have incurred the anger of Myanmar activists and social workers, and consequently, “social punishment” on sites like Facebook. The international community needs to engage with the right local partners to provide aid effectively on the Thailand-Myanmar border.

Myanmar refugees and migrant-focused CSOs have the experience with providing aid in the border areas and social capital with the war on community. During the Lay Kay Kaw airstrikes, for example, Myanmar refugees and migrant-focused CSOs such as border-based charities, Myanmar migrant workers associations, and ethnic region-based CSOs provided aid to refugees with local funding, access which international organisations could not provide. These third sector actors are vital partners for international and long-term access and distribution to aid in Myanmar.

These partners include three key groups. First, Myanmar migrant-based CBOs, especially migrant workers associations in Thailand, are essential intermediaries––despite not being well-known as refugee aid providers. These CBOs are well-established across Thailand, particularly in cities like Mae Sot and Samut Sakhon (Mahachai). Their contributions have provided aid to people in Myanmar long before and after the coup in February 2021.

In limbo: Migrant workers struggle with the Myanmar coup and COVID-19

As their travel documents expire Myanmar migrants risk becoming undocumented and excluded from legal protections by shortcomings in both Myanmar and Thai migration policies.

The second effective third sector actor is ethnic region-based CSOs, such as Karen and Karenni regional organisations who are also essential providers of cross-border humanitarian assistance. They have extensive experience with providing aid in the southern Myanmar, an area plagued by decades-long armed conflict since the 1990s between the Tatmadaw and ethnic armed groups in Karen and Karenni region-based areas. These ethnic region-based CSOs have been the main service providers in healthcare and education and advocates for human rights and environmental issues.

Third, cross-border based charities and refugee camps at the Thai-Myanmar border, particularly in Mae Hong Son, Tak, and, Kanchanaburi are also familiar with international aid, and already possess good institutional support and structures to manage refugee affairs. These CSOs have the network for humanitarian assistances and cross border aid distribution. Because of their institutional capacity and background, these CSOs would be effective service providers if the Bangkok government agrees to new refugee camps at Thailand side.

Tatmadaw offensives in the last few months have not only targeted and destroyed civilian livelihoods and homes; their actions include a wide range of crimes against humanity. If international agencies are eager to provide aid, they should be careful to avoid any engagement with the junta regime, or risk eliminating humanitarian assistance for those who need it most: refugees on the Thai-Burma border in Karen and Karenni state, and IDPs in Karen and Karenni regions.

Relying upon these third-sector organisations also helps to mediate between international agencies and local humanitarian organisations, thereby avoiding engagement with the junta which would anger many in the resistance movement in Myanmar. More attention needs to be given to these border-based actors, as they are the most realistic means of distributing much-needed aid in Myanmar now.

Maung Oak Aww (pseudonym) is a researcher based on the Thailand-Myanmar border. His research specialises in the role of civil society organisations and war on populations in southern Myanmar.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss