Populists change the way we think about electoral strategy. They mobilise new constituencies, they prime new debates, and, most importantly, they shift rhetoric. What was once unsaid, and/or only hinted at, now becomes explicit.

In the United States, populism reoriented the campaign strategies of both the Republican and the Democratic parties. The former “doubled down” on the race-baiting strategy that began with Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy, while the latter created a “blue wave” through a renewed progressivism that opposed everything Donald Trump stood for.

The May 2019 elections—where Filipinos will select their local officials, their district representatives to the lower house, and 12 nationally-elected senators—are the Philippine equivalent of the US midterms and will serve as a referendum on the administration of the so-called “Trump of the East”, President Rodrigo R. Duterte.

Will this election, like its US counterpart, reflect the new rules of a world undergoing a populist explosion? Or will it be a testament to the oft-repeated view that the Philippines is a “changeless land”—a place where all elections follow simple rules of patronage and elite alliance building?

Not the midterm you expect

Duterte’s victory in 2016 surfaced what had already been in the Filipino electorate’s id: a nostalgia for strongman rule, a low regard for human rights, and a disdain for the norms safeguarded by institutions like the Church and elite universities. In 2016, Duterte cursed the pope, told a violent rape joke, and vowed to be a mass murderer. Pundits at the time (myself included) assumed these actions were enough to erode whatever initial support Duterte’s ragtag campaign had generated.

It is now cliché to note that Duterte upended the rules of campaigns in the Philippines. Of course, vulgar populism was not new; cursing and sexist humour were and still are common in local elections. The difference was that Duterte nationalised this local strategy with great success.

The last time such a tidal wave in electoral strategy occurred was after the election of President Ramon Magsaysay (in office 1953-1957), possibly the first Filipino populist. After his election, no presidential candidate could campaign without claiming that his platform represented the interests of the common Filipino “tao”. A patrician nationalist in the mould of Commonwealth President Manuel Quezon could no longer be elected unless he convinced the electorate that he was or could be one of them.

Given Duterte’s success, one would assume that more candidates allied with him would borrow from his electoral playbook, or that those who oppose him would shift their strategy to match or counter his bombast. No such shift has occurred in the Philippines.

Since his election, Duterte has solidified his support among the oligarchs, celebrities, and warlords that constitute the country’s political elite. And these traditional politicians (trapos) seem content to run traditional campaigns. Despite their support for Duterte, their rhetoric, with a few notable exceptions, does not bait controversy like Duterte’s. Nor have they tried to copy the humor that made Duterte sorties popular spectacles. Nor have they selected many political outsiders to join their ranks.

Meanwhile, the opposition has not found an alternative narrative to respond to the hegemony of “Dutertismo”, replicating instead the tired tropes of the anti-dictatorship movement of the 1970s and 80s.

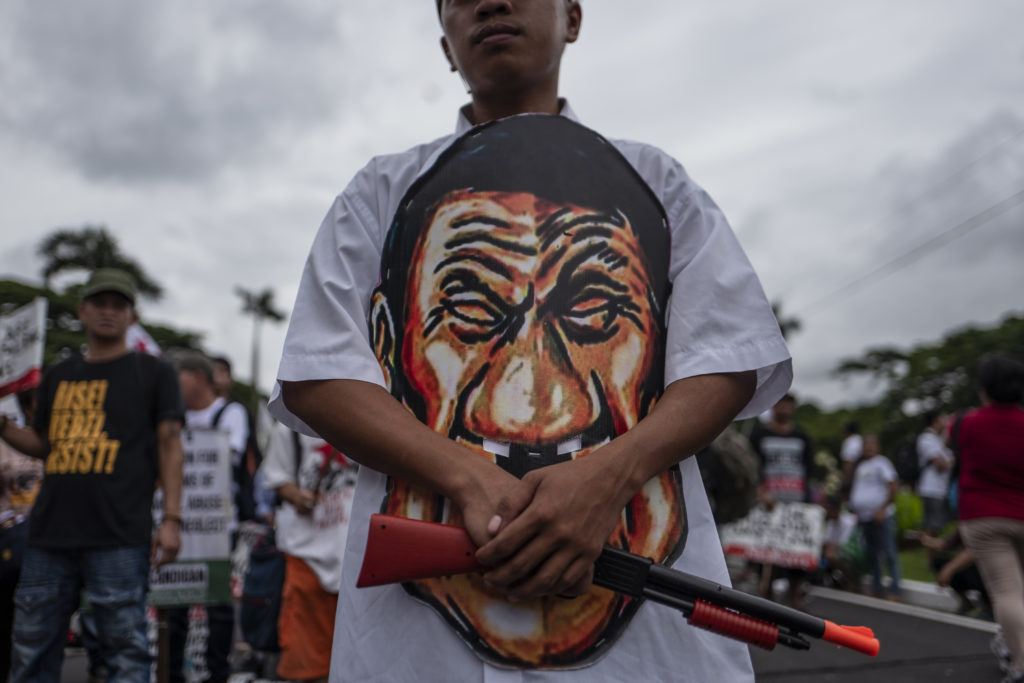

Protests in Manila ahead of the president’s 2018 State of the Nation address. (Photo: Jes Aznar/Getty Images)

Duterte’s party

Duterte’s popularity at the mid point of his term is similar to that of his predecessor’s, Benigno (Noynoy) Aquino, at the same point of his presidency. During the 2013 midterm elections, traditional elites flocked to Aquino’s banner, and a similar phenomenon is happening with Duterte.

Midterm elections in the Philippines are usually focused on the 24-seat senate, where half of the members are elected every three years. The senatorial race receives disproportional media attention, because it is the only national campaign during a midterm. Moreover, the senate’s political bent can change after a midterm election, as politicians experiment with new ways to project themselves unto the national scene.

In contrast, the power base in the lower house (House of Representatives), which consists of vipers loyal to the pork-disbursing sitting president, rarely shifts during a midterm. Senatorial elections are therefore more exciting.

Although the Philippines is a multi-party democracy, midterm senatorial elections often play out as contests between two major coalitions, one in support of the incumbent president and the other in opposition.

As of this writing, Duterte has yet to finalise a list of endorsed candidates for the 12 senatorial positions. But we can already discuss the major blocs within the Duterte coalition and some of the more prominent candidates that will run with Duterte’s endorsement (there is no space to discuss the more minor candidates).

The first bloc is Duterte’s own Partido Demokratiko Pilipino—Lakas ng Bayan (Democratic Party of the Philippines-Strength of the Nation, or PDP-LABAN). Although Duterte is PDP-LABAN’s chair and its most prominent member, he is no party stalwart. Prior to running for president, he belonged to his own regional party—one that formed provisional coalitions with national parties every election season (Duterte supported Aquino and his Liberal Party in 2010).

PDP-LABAN, a minor party in 2016 (although one with important origins in the anti-Marcos struggle), hit the jackpot when it became Duterte’s national electoral vehicle. Had Duterte lost, he would have likely gone back to local Davao politics, and PDP-LABAN would have returned to obscurity. Instead, it became the ruling party, as turncoats, mostly in the lower house, flocked to take their oaths as members.

The party remains vulnerable, however, as other, smaller pro-Duterte parties seek to weaken its base. A particular threat is presidential daughter and Davao Mayor Sara Duterte’s Hugpong ng Pagbabago (Faction for Change), ostensibly a local party that has nonetheless flexed national power. Duterte himself has acknowledged, for instance, that Sara engineered a coup in the House of Representatives that removed PDP-LABAN stalwart Pantaleon Alverez as speaker in favour of the unpopular and corrupt former president, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Nevertheless, for the time being, PDP-LABAN remains the main electoral vehicle for the Duterte camp. Bidding for re-election under its banner is Aquilino Pimentel III, the party’s president and former president of the senate. He is the only PDP-LABAN stalwart of any significance, having been a senator even before the rise of Duterte, and he is likely to be re-elected.

Joining Pimentel are two of Duterte’s most loyal deputies—figures unheard of prior to Duterte’s election. The first is Christopher (Bong) Go, Duterte’s special aide and cordon sanitaire. Though Go rated low in early surveys, his campaign will likely receive funding from businessmen, who correctly view him as a peddler of access to the president.

Like Go, Ronald (Bato or the Rock) dela Rosa, former head of the Philippine National Police and chief architect of Duterte’s bloody war on drugs, is running a campaign reliant on his ties with his boss. Since his appointment as police chief, dela Rosa’s popularity and approval ratings have more or less tracked that of Duterte’s, indicating that Filipinos see him as a surrogate for the president.

Though he does not curse as much, dela Rosa’s humour and dexterous mix of bravado and self-effacement make him the only Duterte-like figure in this campaign season. Ranked in the 8th to 15th range, he is the only candidate from a non-traditional background (not from a political family and not a former senator) that has a strong chance of winning.

The trapo allies

The biggest coalition partner of the PDP-LABAN is the Nacionalista Party (NP)—the country’s oldest extant party, and a natural home for traditional politicians.

The dominant group in the NP is that of real-estate mogul and former senator, Manuel Villar, who sits as the party’s president. Manuel’s wife and current chair, Cynthia Villar, heads a ticket of established politicians from powerful political dynasties. Villar is presently ranked second in the surveys (behind the independent incumbent Senator Grace Poe, whom many pundits thought would win the presidential election of 2016), while a close third is Pia Cayetano, a former senator who is also the sister of Duterte’s vice presidential running-mate (Vice Presidents are elected separately in the Philippines) and former foreign secretary.

The NP’s present line up also features Imee Marcos, eldest daughter of the late dictator and governor of Ilocos Norte province. Marcos is polling similarly to dela Rosa.

NP being led by female candidates is admirable, and Pia Cayetano in particular has a record as a progressive and feminist legislator (She was one of the primary authors of the Reproductive Health Law and vows to make a divorce law her priority if elected). Still, the presence of the NP in the Duterte senatorial coalition reveals the continued entrenchment of trapos at the centre of power.

The Villars are the country’s most prominent rent-seekers, and their success in politics has only been eclipsed by the success of their condominium and land development empire. Manuel and Cynthia’s son, Mark Villar, is Duterte’s public works secretary—an appointment that may have been a reward for the Villar family’s campaign contributions to Duterte. The Cayetanos, on the other hand, are the established political dynasty of wealthy Taguig City in Metro Manila. And as for the Marcoses, they are the most corrupt family in Philippine history.

The opposition and its boring liberalism

The opposition is led by the once mighty Liberal Party (LP). The LP’s power base eroded after 2016 as the usual turncoats shifted allegiance to Duterte’s PDP-LABAN. Moreover, Duterte’s systematic demonisation of the LP-led Aquino administration has rendered the party out of step with the political times.

Nevertheless, the LP remains at the centre of political opposition against Duterte, especially since the Vice President, Leonor (Leni) Robredo, is its present chair.

The LP’s electoral strategy has thus far centred on Marcos-era nostalgia. Last August, it announced its first three candidates. Senator Paolo Benigno (Bam) Aqunio IV, former representative Lorenzo Tañada III, and Jose Manuel Diokno are all namesakes of former anti-Marcos senators. Speaking during the nomination of the three candidates, former President Aquino spoke of the three as “legacy” candidates. Meanwhile, the Vice President Robredo said that the three candidates had “inherited the good names” of their relatives.

Why Thailand’s generals fail to co-opt elections

History and electoral reality suggest that the 2019 elections will deliver another “wasted coup”.

The broader opposition slate, which includes non-LP allies like President Aquino’s former solicitor general, a Muslim feminist and civic leader, a circumspect and progressive former military officer, and Robredo’s crusading election lawyer, shows that the anti-Duterte forces have a wellspring of competent advocates to draw from. Being in a position of weakness, moreover, has allowed the LP and its allied organisations to rid themselves of opportunists and turncoats. This does not, however, mean that the opposition has found a winning formula.

Respectable as their efforts might be, the opposition is misguided to portray their campaign as a rehash of the anti-Marcos struggle. Duterte won partly because old anti-dictatorship rhetoric had lost its lustre, amid a disillusionment with the system of oligarchic democracy that replaced authoritarianism.

The opposition requires a new political narrative for the Duterte era. That they have not found one is not for lack of trying. The LP under Robredo has done its best to present a more humble image of itself as part of a long-term rebranding strategy. Though this strategy may not bear fruit in this election, it may benefit the party and the broader opposition once the Dutrete regime’s contradictions (the tensions within its elite political coalition, its dependence on China, its inconsistent economic policy, its arbitrary implementation of justice) become more pronounced.

Programmatic politics in the Philippines?

The elections of 2019 in the Philippines will showcase the resiliency of political dynasties, turncoats, and rent-seekers. In this sense, it will be a normal Philippine election. Yet the rehabilitation of Philippine authoritarianism gives this midterm election an ideological quality absent in previous ones. Prior to Duterte, midterm elections were just referenda on personalities. This one is that, but it is also more. Since Duterte and his dictatorial policies are at the centre of this election, it will also be a referendum on democratic values like checks on power and human rights. The results will likely disappoint us.

Still, democracy has not eroded enough to make me believe there will not be another election in 2022. And one may hope that things get better by then.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss