As a populist, Duterte’s erosion of the rule of law is no surprise.

Since Rodrigo Duterte became president of the Philippines on 30 June, the country’s already compromised rule of law has taken a battering in his new war on drugs.

More than 700 people suspected of links to the drug trade have been killed, either directly by the police, or by vigilante groups. Earlier in August, Duterte warned more than 150 judges, politicians, and police officers that they will be next in line for termination unless they voluntarily surrender immediately. The president has even declared his readiness to impose martial law if the judicial branch interferes with his war on drugs.

Duterte’s distain for due process is remarkable for its explicitness. But the erosion of the rule of law that has already taken place under his government shouldn’t come as a surprise.

By any definition Duterte is a populist and this fact tells us a lot about what we might have expected from his presidency. Recent research I conducted with Christian Houle on populism in Latin America shows that populist governments systematically undermine the rule of law and the autonomy of the judicial branch.

A populist is a charismatic leader who tries to mobilise mass constituencies through the media and mass rallies in his or her quest to gain and retain power. Populists are notable for using radical rhetoric in which the establishment is portrayed as evil or corrupt while ordinary people are presumed to be good. Because populist rhetoric can be combined with other ideologies or issue positions, populists can be either on the left (liberal) or on the right (conservative).

Duterte fits this description well. He frequently violates norms of political correctness, hurling swear words, and misogynistic and homophobic insults in interviews and speeches. He portrays himself as a common man of the people in opposition to the corrupted elite. During the presidential campaign voters were captivated by his dramatic promises to end crime and corruption in six months. For Duterte, drug dealers and addicts are beyond redemption, no longer members of the community of people. He has no mercy for them. As he has said: “If you are involved in drugs, I will kill you. You son of a whore, I will really kill you.”

Legislatures, judges and the rule of law more broadly can constrain the executive branch, even in presidential systems; these institutions have become essential to liberal democracy as they restrain the leadership from abusing its authority. Populists often claim that their popular mandates override legal niceties.

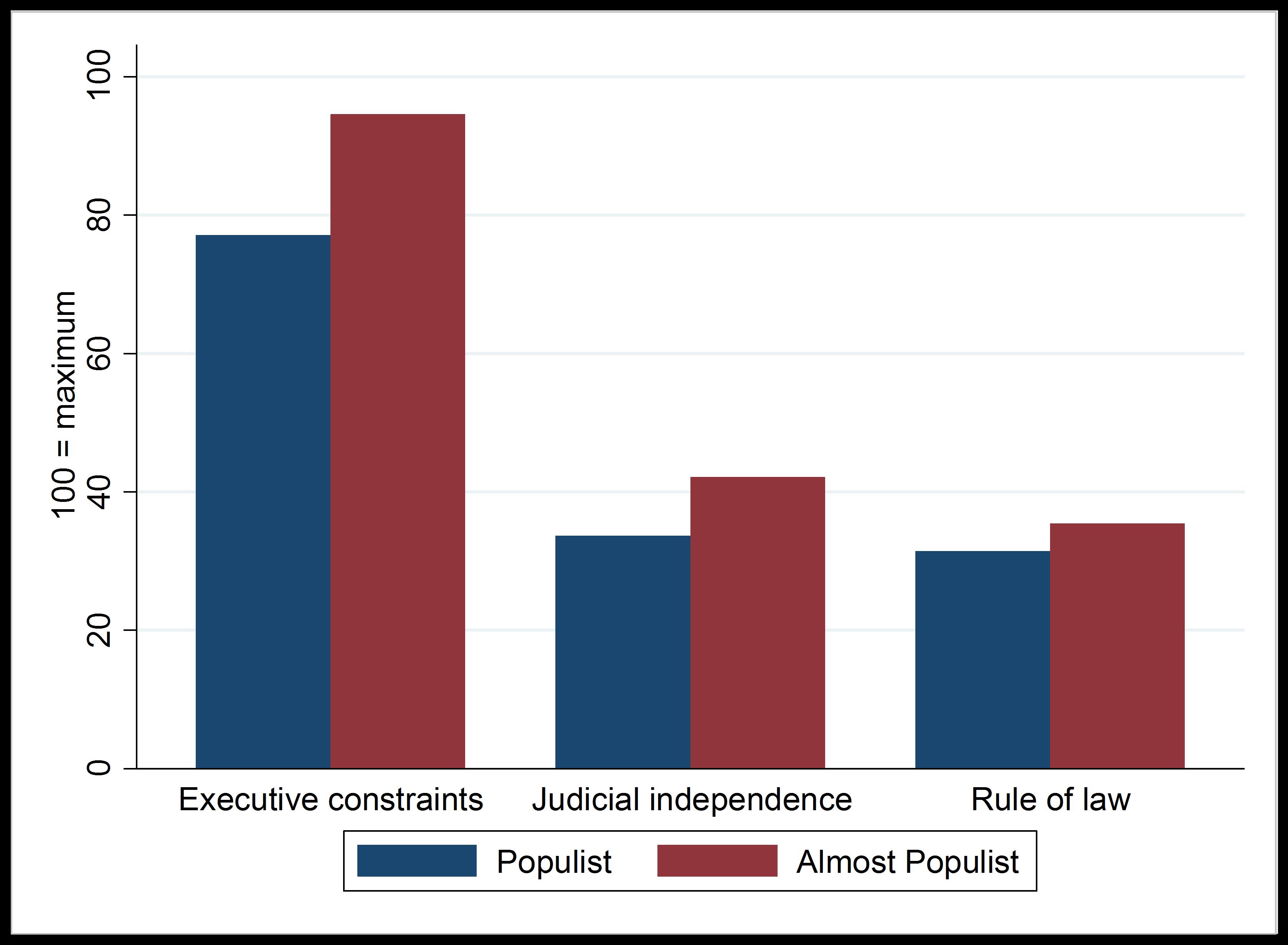

Populist presidents across Latin America have cowed the judicial branch and even rewritten constitutions to allow for repeated re-elections. In fact, even with almost identical starting conditions, Latin American countries in which populist candidates are successful (‘populist’) versus ones in which populist candidates are narrowly defeated (‘almost populist’) end up with a 19 per cent lower level of constraint on the executive, a 20 per cent lower level of judicial independence and an 11 per cent lower level of the rule of law.

Not only has Duterte sanctioned a massive program of extrajudicial killing, but he has objected to the very constitutional limits on his power. He has promised a constitutional change, opening up the possibility that the authority of the president will be further enhanced and the constitutional prohibition on re-election overridden.

As Nils Bohr famously quipped, “prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” Yet in this case, it was easy to see what was coming with a Duterte presidency.

Paul Kenny is research fellow of political and social change at the Australian National University.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss