After 5 years under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, some argue that terrorism, insurgency, and political violence in the Southern Philippines are waning under the combined pressures of military and law enforcement operations, peacebuilding initiatives, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Armed Forces of the Philippines report mass surrenders of terrorists belonging to disparate groups ranging from the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), and the New People’s Army (NPA); they claim that an end to decades of conflict is in sight.

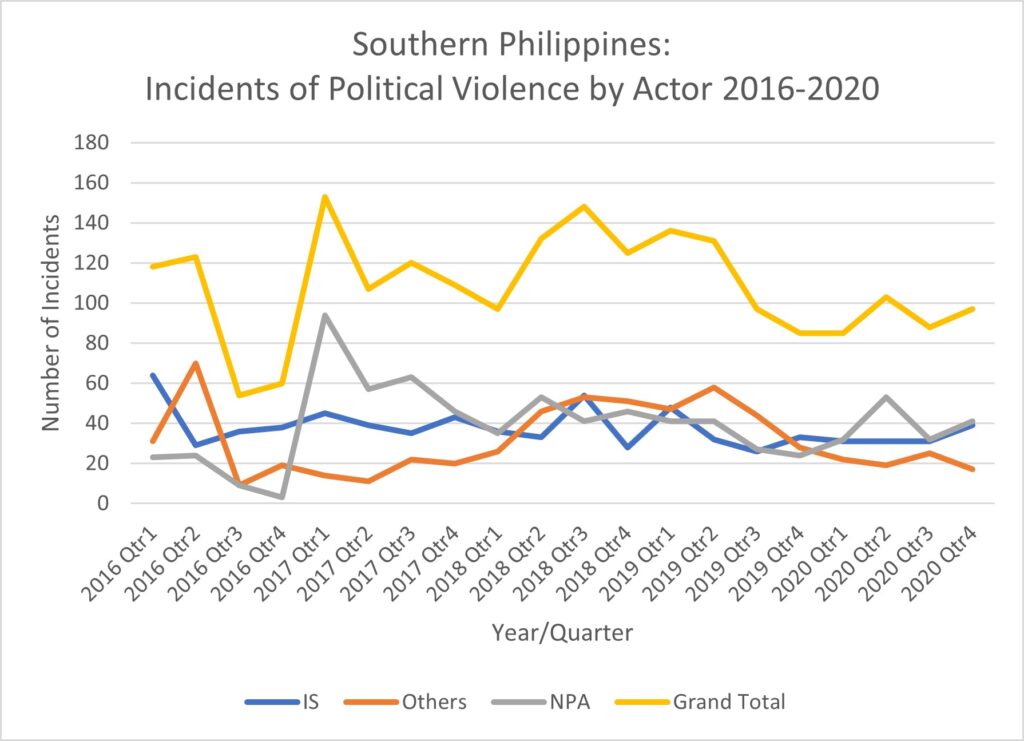

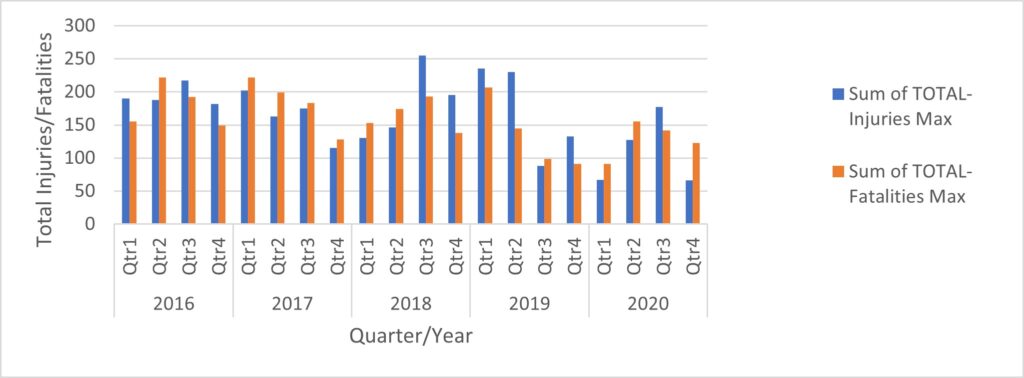

From 2016 to 2020, my Political Violence in the Southern Philippines dataset captured a decline in the number of violent incidents, from a peak of 502 incidents in 2018, to 449 in 2019, dropping to 375 incidents in 2020. Despite this, political violence in the Southern Philippines has not ebbed past its lowest point in 2016, nor is there any certainty that political violence will not return to prior heights in the year to come. While the data cannot fully explain conflict trends or offer ironclad predictions, fluctuations in the incident and casualty data when refined by actor category, incident type, and location support a cynical reading of claims presaging the end of the Philippines’ major insurgencies. These sub-aggregate trends in the data may suggest that other phenomena including election cycles, local weather effects on agriculture, and the ongoing pandemic are mediating violence in the Southern Philippines in ways that are not yet clear to observers. Due to these uncertainties it is most prudent to observe that conflicts on the wane are not necessarily conflicts approaching their end.

Data Parameters and Methods

For the purposes of this project, political violence is defined as the use of violence to damage or destroy people and/or property with the intent of advancing a political ideology. This definition is broad enough to encompass incidents of police violence against protestors and church bombings committed by professed members of the Islamic State. It does not include most varieties of robbery, manslaughter, and homicides driven by acute personal grievances, such as an argument between two individuals that escalates to the point of violence. Real world violence seldom conforms to academic typologies, thus coding erred on the side of inclusion in marginal cases.

Incidents relating to the Battle of Marawi and War on Drugs-related killings were excluded, not because they do not constitute episodes of political violence, but because they were beyond my capacities to reliably record and code. In the case of Marawi, breaking down the 6-month long siege in incidents that could be reliably tied down to a single date and specific location (barangay) was not possible, but may become feasible in the future as investigative journalists and scholars uncover a day-by-day order of battle account drawn from official documents and witness testimony. As for incidents stemming from President Duterte’s War on Drugs, these cases were too numerous and the incident data often so obfuscated that even the International Criminal Court is struggling to unravel the true extent of the extrajudicial killings.

Observations and Trends

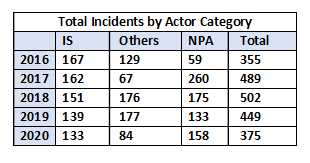

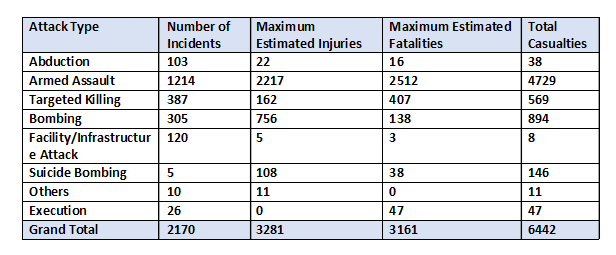

From 2016 to 2020, the dataset recorded 2170 incidents of political violence in the Southern Philippines, which wounded between 2910 and 3281 individuals and claimed 2760 to 3161 lives. During this time the total number of incidents was at its lowest point in 2016, before peaking at a total of 502 in 2018. The subsequent decline in incidents from 2019 to 2020 can be attributed to a number of factors, including the combined effects of heightened regional security under martial law after the Siege of Marawi, gradual progress in the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of fighters from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, and the impact of the pandemic.

The graph above shows that the sharp decline in total incidents from Q2 to Q4 2016 corresponds closely to the trendline of the NPA during that period. This is likely because the NPA was observing a truce with the government that fell apart in Q1 of 2017, hence the spike in incidents recorded at that point in time. The second major decline in the total number of incidents occurred between Q2 of 2019 and Q1 of 2020, but while this decline mirrors the fall in incidents associated with the category of Others (incidents attributed to unknown actors, state actors, or minor actors that did not fit into another category), there was no obvious sequence of events that might explain the sudden drop in incidents.

Broken down by categories of actors which are the Islamic State (IS), the NPA, and Others, the set captures a gradual decline in IS-associated from 2016-2020, whereas incidents associated with the NPA and other actors followed no discernable pattern at first glance. In addition, incidents associated with actors under the category of Others peaked in Q1 and Q2 of the years 2016 and 2019. This closely aligns with the national and local election seasons that occurred at those times. On closer examination of the incident data during these periods, it is apparent that many incidents occurred at or near polling places, while other incidents involved political candidates or persons associated with political candidates (e.g. staff, family, supporters, etc.). In the end, the NPA was responsible for the largest number of incidents over the past five years, and was also responsible for more incidents than IS groups.

The toll of political violence in the Southern Philippines cannot be overstated, and it bears mentioning that the casualty figures do not capture the full costs of conflict. This dataset recorded 6,461 casualties consisting of 3161 fatalities and 3281 injuries from 2016-2020, and the total number of casualties declined gradually and unevenly over the whole of the period. Though not pictured on the chart above, fatalities and injuries associated with IS groups declined alongside the total number of associated incidents, with the exception of Q1 and Q2 of 2019. Combined casualties (fatalities and injuries) from Others peaked in Q4 of 2018 before declining to similar levels as in 2016. NPA casualties peaked in 2017 before declining through 2018. However, where injuries from NPA associated incidents continued to decline from 2019-2020, fatalities increased from 97 to 168 at the same time.

This total can also be broken down further into four categories of actors who suffered casualties, which are Armed Non-State Organizations (NPA, BIFF, the Maute Group, ASG, Ansar Khalifa Philippines, the Moro National Liberation Front, and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front), State Security Services, and Civilians. Across all incidents, militant organizations made up 41% of all casualties, while state security forces and civilians made up 32% and 26%, respectively.

Armed Non-State Organizations killed and wounded thousands of security forces and civilians, but rarely left the fray unscathed, making armed assaults the most common and destructive attack type recording in the dataset. These kinds of attacks involved the greatest variety of weaponry, which ranged from the small arms and light weapons of militant groups, to the heavy arms and air support of state forces. Often, the scale of these clashes using combined arms led to significant civilian casualties and displacement, though the latter was not recorded in the dataset. Suicide bombings, though rare, are highly destructive when they do occur, whereas attacks on infrastructure and facilities are the least destructive of all incidents in terms of human life.

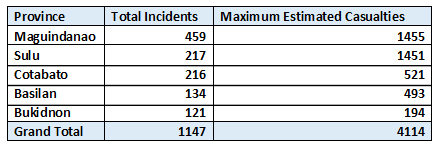

The total number and various qualities of incidents also varied considerably by province, with each administrative area demonstrating unique trends. These trends are exemplified by the provinces of Maguindanao, Sulu, Cotabato, Basilan, and Bukidnon, which were the 5 provinces with the highest total of incidents from 2016-2020.

Of these provinces Maguindanao consistently suffered the greatest number of total incidents each year, as well as the most armed assaults, targeted killings, and bombings each year, but only suffered the most casualties in 2017 and 2018. The most intense violence in Maguindanao was attributed to the operations of the BIFF, although other sources of conflict including clan feuds (Rido) sparked by property disputes and electoral violence were also important contributors to this trend. By 2019, however, Sulu suffered the highest casualty rate of any province, which can be attributed to the adoption of suicide bombings as a mode of mass casualty attacks by the ASG. In addition to suicide bombings, regular clashes between the ASG and security forces contributed greatly to the number of casualties in the province. The emergence of Cotabato and Bukidnon among the top 5 most violent provinces in recent years demonstrates the capacity of the NPA to conduct ambuscades, targeted killings, and attacks on commercial infrastructure/property therein.

The value of post-conflict inclusion of youth

How do young people contribute to addressing injustices and advancing agendas of peace?

In contrast to the optimistic projections of the Duterte administration, the impact of state-led counterinsurgency and counterterrorism against the Southern Philippines’ various IS factions appears modest at best, particularly in Maguindanao and Sulu where the ASG and BIFF continue to weather clearing operations and launch attacks of their own. Despite the losing several leading members of local factions over in recent years, the ASG’s demonstrated resilience and well-established presence in Sabah, Malaysia strongly suggests that the group can recover from its losses. Foreign fighters remain a concern in this regard, as they not only add to the numbers of militants active in Mindanao, but have played an outsized role as suicide bombers in Sulu.

In addition, the long-delayed reconstruction of Marawi City will continue to be a source of frustrations for the thousands of former residents still displaced by the siege of the city by a collation of militants organized by the Maute Group of Omarkhayam and Abdullah Maute. Nevertheless, violence involving militants affiliated with the former Maute Group in Lanao del Sur has not yet escalated beyond occasional encounters with security forces. At the same time the NPA became more active, being involved in the least number of incidents in 2016 to the highest number of incidents of any category of actor in 2020, casting doubt upon the administration’s claims of defeating the region’s oldest communist insurgency.

Just as the future of political violence of in the Southern Philippines is in doubt, the inner workings of these various conflicts remain difficult to explain. Why the NPA appears to have had greater success sustaining its operations than any IS-aligned group is not immediately clear, nor is it obvious why NPA associated incidents experienced a spike in fatalities between 2019 and 2020. Similarly, why Q2 of 2019 was evidently a turning point leading to the overall decline of political violence in the region is also unclear and perhaps even surprising, given that it precedes the emergence of Covid-19 in 2020 as a potential conflict dampener.It is likely that there may be seasonal variations in political violence correlating with the annual cycle between the wet season (May-October) and dry season (November-April), with incidents falling during the productive agricultural months of the wet season and rising with the fallow dry season. However, recent scholarship on conflict and rainfall in the Philippines has found a closer relationship between unseasonal shocks including flooding, droughts, and unexpected rainfall during the dry season and the onset of conflict. Based on research in this field, another study tracking regional rainfall patterns in Mindanao that takes into account the local characteristics of agricultural production could offer a more compelling explanation of overall trends in violence beyond seasonality.Generally, research attuned to the distinctly local character of political violence in the Southern Philippines holds the greatest potential to unravel the patterns behind decades of violence, which would enable scholars, policymakers, and peacebuilders of all kinds to chart a path to a more equitable peace in Mindanao and Sulu.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National War College or the U.S. Government.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss