In the decades since the beginning of the Reformasi, young people living outside of Indonesia’s cities have navigated contradictory relations of agrarian transformation and rural inequalities. Food and agricultural policies have required the rural poor to be increasingly self-reliant in the context of profound social, economic and environmental change. Their livelihood outcomes have been uneven in trajectories of economic growth and land development. These have involved social justice movements and struggles against corporate land investment.

Some agricultural households have prospered through specialising in newly emerging economic structures (e.g. smallholder palm oil) but many more have sustained themselves by combining agriculture with work in non-farm sectors. In response to rural production constraints, such as declining soil fertility and loss of agricultural land, smallholder livelihood diversification strategies have involved the multi-directional movement of household members between sectors and places far from natal villages.

New entrants into this emerging shift in livelihoods are increasingly being led by Indonesia’s burgeoning youth population. Diversification strategies may mean that young people have been supplementing family income through off-farm work and sending remittances home to their families, or that their parents have engaged in migration-based employment to provide them with remittance-funded higher education.

Recent research suggests that more young people are leaving the countryside in pursuit of diversified non-farm livelihoods. Issues of education, employment and migration are prominent among rural youth. Questions concerning who then farms as rural populations age and how food security is achieved are now emerging. The same holds for whether the social and economic aspirations of young people are being met in peri-urban and urban centres. How do these agrarian changes impact upon the social and economic opportunities and aspirations of rural youth in these different settings?

While much research on youth aspirations and rural change has taken place in the populated island of Java, less is understood about the role of young people and their aspirations in the outer island regions. This certainly holds for the island of Sulawesi and its southern portions.

South Sulawesi occupies a strategic position as a gateway to Eastern Indonesia and has a large agricultural base. It is ranked as one of the most food and nutrition secure provinces, but losses in rice production due to droughts and flooding are likely to be exacerbated by climate change. Agricultural land under irrigated rice (sawah) cultivation has been relatively stable despite an overall declining contribution of agriculture, forestry and fisheries to the regional economy.

Up until recent changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, young people have negotiated economic and social transformations in South Sulawesi similarly to those in other regions. The profile of young people is indicative of national trends of increasing higher education and the employment of young people in non-farm sectors. It is also indicative of national trends of high unemployment among young people moving to cities where unemployment is higher than in rural areas.

Agricultural statistics tell us that in 2018 around 1 million households engaged in the agricultural sector. These households make up almost half of a total population of nearly 9 million, of which 1.61 million people listed their occupation as farmers. More than 90% of agricultural households own less than 4 hectares of land and in 2018, and subsistence (gurem) households owning less than 0.5 hectares comprise 38.79% of agricultural households. This indicates land inequality.

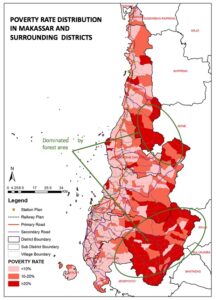

The highest number of farmers is in the 45 to 54 age group and 65.3% of these farmers have primary school education or less. Young people’s level of education is higher than their parents and grandparents but there are disparities in access to education and health based on where people live, particularly in rural areas where services are less available. Provincial statistics tell us that the poverty rate of 9.06% is lower than the national average, but there is significant poverty in rural areas. The poverty rate is higher than 20% in forested and rural hinterlands surrounding Makassar while less than 5% in the provincial capital.

Poverty Map. (Source: RBI Map 2016 and Smeru 2015)

Based on preliminary data, a collaborative initiative under AIC PAIR has started to document trends in young people leaving the impoverished hinterlands, while the provincial capital of Makassar and its surrounding industrial zones have experienced significant growth in the numbers of young people.

Demographic changes have coincided with significant national infrastructure spending. The new Makassar seaport will connect to a 150-kilometre railway network from Makassar to the port town of Parepare. The railway is part of an ambitious 1,700-kilometre trans-Sulawesi project that would eventually circle the entire island. The new terminal of the Sultan Hasanuddin International Airport was opened in 2008. Near the airport, the Bosowa cement factory in Maros district has a production capacity of 4.2 million tonnes per year. Meanwhile, the seaport and railway will directly link to Bosowa and Tonasa, another large cement factory in nearby Pangkajene dan Kepulauan (Pangkep) district undergoing expansion, with an associated decline in the number of agricultural households since 2013.

Gender and poverty

The agrarian change picture in South Sulawesi suggests that where young people engage in on-farm work, their labour is heavily influenced by pre-existing gendered social relations of production and exchange. Other factors, such as the size of landholdings, may limit their opportunity to contribute to on-farm work. Indeed, differentiated gender relations are prominent in both agriculture and fisheries sectors, which are dominated by men. In 2018, only 17.3% of farmers were women.

The coastal district of Pangkep has one of the highest poverty rates of 15.1%. Seaweed farming as a cash crop has increased along the coastline, where many households rely on capture fisheries. Younger women often work in family relationships in the intensive parts of seaweed value chains including in preparing the ropes and tying seeds to the ropes, and later in the drying and processing of the seaweed. Their vital roles are seldom recognised in aquaculture and fisheries sectors—an industry to which physically able young and middle-aged men increasingly gravitate.

However, in the urban areas fringing rural hinterlands, we see a greater proportion of young women involved in education and health sectors. For example, in the urban areas of Maros district, among the 25 to 29-year-old cohort in 2015, there were 273 women and only 132 men involved in educational services. Population statistics tell us that this discrepancy grows in the next age cohort with 631 women and only 260 men between the ages of 30 and 34 employed in education.

Those seeking university degrees often desire upward mobility and a life different to their parents, but the transition to salaried positions can be illusory for those from poor and migrant backgrounds. Not all young women “transition” from school leaving to higher education, and the province has high rates of child marriage. While it is likely that salaried positions are being filled by educated young women, it is unclear what number, if any, of these young women are from the hinterland areas surrounding Makassar and other impoverished regions.

Based on our preliminary data and these other reports, we see several different agrarian and potential youth employment trajectories unfold across rural, coast and urban settings in South Sulawesi with as yet poorly understood impacts and outcomes. While it is clear that rural youth outmigration is occurring in Maros district and South Sulawesi more generally, less known is about the uneven experiences and impacts of these transitions within and between young women, young men, and their families.

As urbanisation and industrialisation expand along the peri-urban fringe of Maros and the surrounding coastline of Makassar, how will young men and women be differentially incorporated into labour and markets? What are the gendered livelihood impacts and outcomes? For example, if young men are incorporated into construction and concrete industries, and young women into the processing of industrial grade seaweed, what gendered labour conditions and related issues of human rights will arise?

What is clear is that these trajectories are experienced differently across young men and women with varying degrees of success and failure. Youth unemployment, particularly young men, is highest in cities, yet young women, who tend to stay in school longer—and especially those who secure jobs in the education sector—will likely fair better overall. Several questions thus remained unanswered. As young people leave rural areas, who is left behind to produce food and care for the elderly in their households? What are the implications of this for food production and familial food security?

The arrival of COVID-19

Despite the relative success and failure in any livelihood transformation across changing landscapes, as of late the relative impacts of such transitions seem to have been powerfully ‘truncated’ —a notion the speaks to how livelihood pathways and opportunities are quite literally cut short, leaving young people with unfulfilled aspirations and dreams.

With the arrival of COVID 19, pre-existing inequalities will likely now intensify. As both rural, coastal and urban supply and finance chains are ruptured, how will the rural and urban poor maintain food access and production and household nutrition? Government social protection measures have provided support for those without income during the immediate health crisis and disruption to agricultural supply chains, but what long-term structural change is needed?

With the spread and impact of COVID-19 it is unclear whether young women’s employment gains will be maintained and whether those youth employed in the coastal sectors will continue to earn an income. Is the pandemic likely to worsen trends such as youth unemployment in Makassar or in other industrial sectors ? Might some of the young people who departed from rural areas in search of new opportunities in bustling cities now be returning to the rural hinterlands and coastlines of South Sulawesi?

Young people returning home from urban jobs will likely be settling back in with their parents or otherwise. What does this “return” look like? As young daughters (and sons) return home to the “land”, or the “coast”, how is their lost remittance income covered? What are the generational impacts within agricultural households that have relied on this income? While some returnees will experience difficulty “returning” and “fitting in”, negative assumptions that young people are unstable and easily fall into crime are unhelpful. These stereotypes miss the potential leadership and other contributions of young people. As “returning youth” bring new ideas and knowledge home, how can this be harnessed in ways that enable them to navigate contradictory relations and disrupted education and employment pathways?

The pandemic highlights the need for expanding social protections and identifying those who are falling back into poverty. It also highlights the importance of diversifying local food production, not primarily on securing domestic supply of rice and other staple foods. Via Campesina’s emphasis on food sovereignty as ‘the right of peoples to define their own agriculture and food policies’ differs from the emphasis in the 2012 Indonesian Law on Food on the role of the state to ensure food security. We see the potential of emerging young peoples’ food movements that espouse locally-based and sustainable food production. Across Indonesia, young men and women are already working with Via Campesina to further engage food sovereignty through creative forms of rural and urban food production and agroecology. In these movements, the involvement of young people in food production is valorised. Such production entails sustainable and decentralised supply chains and localised distribution in ways that can help to overcome the impacts of COVID-19 on rural poor beyond the immediate health crisis.

Over the next two years, our team of Indonesian and Australian researchers will address these complex questions by examining how young men and women are positioned in agrarian and coastal change in South Sulawesi in the context of COVID-19. Based on results so far, supplementing and strengthening what is already done well in terms of rural and coastal food production is perhaps the best way forward

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss