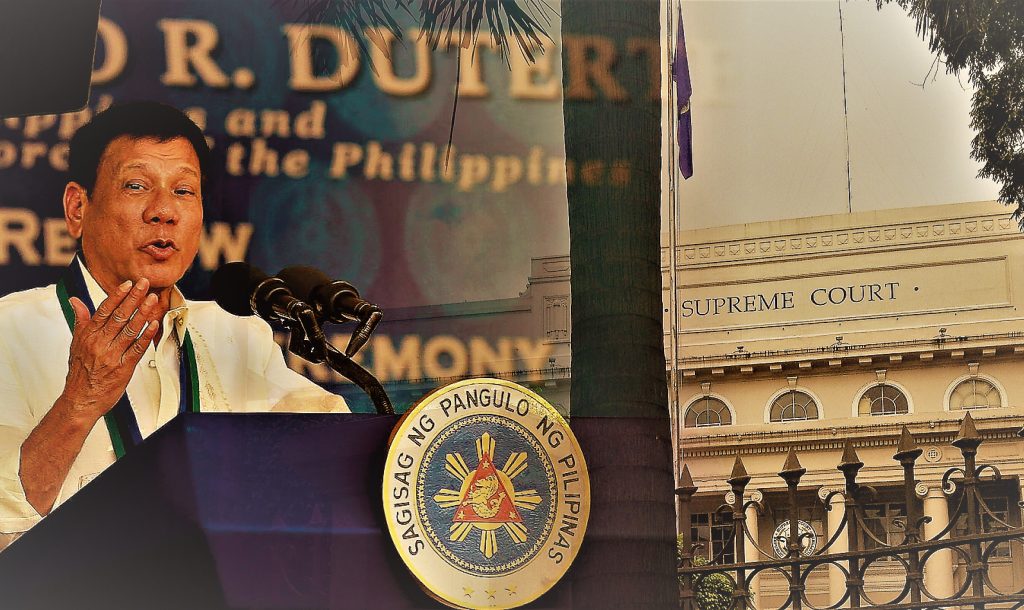

With the ouster of Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, the Philippines finds itself in a precarious political threshold uncomfortably reminiscent of authoritarian rule not seen since Ferdinand Marcos. The removal of the Supreme Court chief justice and threats against other high-ranking officials has eroded the country’s democratic liberal institutions and threatens to push the country further into illiberalism.

Sereno, one of the youngest appointed justices to head the Supreme Court and the first female in that post, was the first impeachable official ousted by the Court through a decision granting a quo warranto petition filed the by the Solicitor General, the government’s lawyer. Under procedural rules, a quo warranto is a legal action to challenge a person’s right or authority over an office. The Supreme Court decision rendered moot what had been a likely impeachment vote against Sereno by the majority-controlled and Duterte-aligned House of Representatives.

A weak impeachment case

Seen as a critic by the administration, Sereno had been publicly threatened with impeachment by the President, who claimed that she is part of a plot to oust him. Last September, the House Committee on Justice accepted a complaint filed by a Duterte-allied lawyer, Lorenzo Gadon, alleging that Sereno committed culpable violation of the constitution, corruption, and other high crimes. Sereno was accused of failing to disclose income earned before her appointment, delaying and manipulating actions on petitions before the Court, purchasing a luxury vehicle for her official use, and overspending for official trips, among others. Charges also included betrayal of public trust by criticising President Rodrigo Duterte’s imposition of martial law across a third of the country, practicing favoritism with judicial personnel, making public statements in reply to the president’s accusations of judges being involved in the drug trade, and preventing justices of the court of appeals from making courtesy calls to Duterte in an effort to separate the co-equal branches of government.

Sereno’s lawyers, who were barred from attending the months-long Congressional hearings, asserted that the charges were baseless and did not constitute impeachable offenses. Even as testimonies and documents presented had failed to produce compelling evidence, the House committee on justice recommended Sereno’s impeachment for a House plenary vote.

Impeachments under the 1987 Constitution

The use of impeachment is nothing new in the Philippines. Former President Joseph Estrada faced impeachment in 2000 before being ousted in a popular revolt. His successor, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, was charged with numerous unsuccessful impeachment complaints. And in 2011, the House of Representatives voted to impeach both Ombudsman Merceditas Gutierrez and Chief Justice Renato Corona. Gutierrez resigned before the Senate impeachment court was convened, but Corona was successfully convicted for betrayal of public trust.

MARIA LOURDES SERENO (PHOTO: SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES)

The 1987 Philippine constitution, adopted after the ouster of former president Ferdinand Marcos, was designed to limit abuses in power. It provides for a stronger tripartite system of checks and balances, independent constitutional commissions, and the office of the ombudsman. The constitution provides that the president, vice president, members of constitutional commissions, ombudsman, and justices of the Supreme Court can be removed by impeachment while all other officers may be removed as otherwise provided by law. Legal experts and scholars, including drafters of the 1987 Constitution, have interpreted this provision to mean that impeachment is the sole means of removing impeachable officers.

The constitution also limits grounds for impeachment to culpable violation of the constitution, treason, bribery, graft and corruption, other high crimes, and betrayal of public trust. While this does not obscure the fact that impeachment is inherently political, adherence to strict legal standards has prevented, or short-circuited, many past efforts.

Politicising the Supreme Court

What we see now, however, is an increasingly politicised process and a deliberate lowering of legal standards. For instance, while some see a parallel between the removal of both Corona and Sereno, the two cases have significant legal differences. Both Sereno and Corona—Sereno’s predecessor—have been accused of failing to make truthful declarations in their statement of assets and liabilities. In the case of Corona, however, he was charged with and later admitted to failing to declare assets worth millions of dollars in unexplained wealth during his incumbency. Meanwhile, Sereno was charged with failure to declare income (as opposed to assets as required under the law) that she earned prior to her appointment to the Court.

RENATO CORONA (PHOTO: SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES)

The most glaring difference, however, is the means by which the two chief justices were eventually removed and the corresponding role that the Supreme Court played. Corona was impeached by the Lower House and convicted after a months-long televised trial by the Senate, where he testified and admitted to failing to declare millions of dollars in foreign currency bank deposits. In the course of Corona’s trial, the Supreme Court ruled in his favor in several related cases. In one case, the Court refused to provide Court documents and records requested by the House impeachment prosecution panel. The Court also blocked the implementation of the Senate’s subpoena of Corona’s foreign currency bank deposits. On the other hand, in the Lower House justice committee hearings on the Sereno impeachment, fellow justices and employees of the Supreme Court attended and testified against Sereno.

The impeachment vote against Sereno was eventually aborted by the Solicitor General’s quo warranto petition. Voting 8 to 6, the Supreme Court ruled that Sereno’s appointment as chief justice was invalid for her failure to comply with the requirement of submitting statements of assets back when she was a law professor at the University of the Philippines, long after the one-year prescriptive period provided under the rules on quo warranto. Seen as a substitute for a weak impeachment case, the Court’s decision has been criticised by the Integrated Bar of the Philippines, deans, and professors from top law schools as circumventing the rules on impeachment, the sole constitutionally recognised mode of removing the chief justice.

Impeachments under the Duterte administration

Aside from Sereno, Duterte and his allies have moved to impeach three other high-ranking officials who were deemed to be critical of his administration within the past year.

Vice President Leni Robredo, who is allied with the opposition, faced two impeachment threats last year filed by Duterte allies. Both charged betrayal of public trust and culpable violation of the Constitution, based primarily on Robredo’s video message to the United Nations criticising the administration’s war on drugs, especially the extrajudicial killings.

In another impeachment case, Commission on Elections Chair Andres Bautista was accused by the Duterte-allied Volunteers Against Crime and Corruption (VACC) of failing to declare certain properties in his statements of assets and to prevent the hacking of the Commission on Elections website. The House justice committee earlier dismissed the complaint, finding it insufficient in form. And despite having announced his resignation, the House plenary still voted to overturn the dismissal and impeach Bautista.

Finally, there have also been impeachment threats against Ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales after her office announced it was investigating the Duterte family’s alleged multi-billion-peso wealth. The President accused Morales of selective justice and use of falsified documents. The VACC submitted a complaint against her in Congress last December but no lawmaker has endorsed it so far.

The stakes

Much is at stake for the country and its democracy when impeachment and other legal remedies to remove high officials are being used to target critical voices and dismantle the protections of a Philippine constitution expressly designed to hinder such abuses.

Operating as they do at the junction of law and politics, the current impeachment and quo warranto cases draw attention to Duterte’s agenda for a political reordering of the post-Marcos liberal architecture. What appears at first as a mere personal impulse of the president is ultimately calculated and strategic: he is using impeachment and, now, quo warranto to deliberately silence dissent and demolish veto gates in the institutional system.

The removal of a critical Vice President, for instance, would eliminate the possibility of an agenda-threatening leadership change should the President’s ill health deteriorate. Similarly, removing the Ombudsman and Election Commissioner tampers with horizontal accountability mechanisms to control hyper-presidentialism—the excessive presidential powers that stem from weak party politics that characterise the Philippines.Above all, the removal of Sereno clears the path for greater control of the Supreme Court, which has the power to derail Duterte’s political plans for constitutional change as well as serve as a check to controversial policies, such as his violent war on drugs.

Understanding impeachment and judicial politics in the Philippines can tell us much about the future of Asia’s oldest democracy. One thing already seems clear: liberal constitutional practice is more fragile than expected. Its outcome is sure to be watched closely by neighboring leaders who may be only too eager to embrace and encourage populist illiberalism.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss