In cooperation with the convenor, Nhu Truong, New Mandala is pleased to share a series of articles based on papers presented at the People’s Power and Resistance in Southeast Asia Roundtable at the 35th Biennial Conference of the Canadian Council for Southeast Asian Studies. You can read Nhu Truong’s introduction here.

In the digital manifestation of coup-related contention in Myanmar, the military both projects an image of itself as championing “true democracy” and reframes resistance activities as destructive for political stability. On the other hand, dissident forces focus their online activism primarily on anti-military narratives and broadcasting protest activities in order to motivate and mobilise grassroots resistance to the coup. While online anti-military content has been more effective at attracting engagement than pro-military content, this gap has narrowed over time. This suggests that dissidents have increasingly confronted digital barriers to mobilising despite widespread public support.

Since March 2021 we have used CrowdTangle, a social media monitoring platform owned by Meta, to collect the 20,000 most viral public Burmese posts from all Burmese-language Facebook pages and groups per day. We then created a random sample of 5,200 posts over 13 weeks, from the beginning of March to the end of May 2021, to obtain a general understanding of digital contention in the early months following the coup. As Facebook is by far the most popular social media platform in the country, examining Facebook content allows us to capture the essence of Burmese social media.

Existing reports claim the Tatmadaw has actively employed public and covert propaganda to manipulate narratives that frame protestors as criminals, in order to turn public opinion against the resistance and in favour of the military. In our original dataset, we find similar content across pro-military pages and groups. This includes labeling Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) participants and ethnic armed groups as riotous; blaming CDM doctors for the 3rd wave of COVID-19; spreading disinformation accusing activists of destroying schools, universities and monasteries, and of attacking innocent civilians; and even framing people who withdraw money from their bank accounts as sabotaging the military administration.

However, pro-military online content was contained and had limited influence. Only 1% of total posts or 3% of coup-related posts were pro-military, and most of these posts attracted under 200 interactions. An important question is whether social media simply reflect a pre-existing lack of support for the military or whether, by promulgating a variety of voices that debunk military propaganda, these platforms themselves generate greater distrust in the Tatmadaw’s rhetoric.

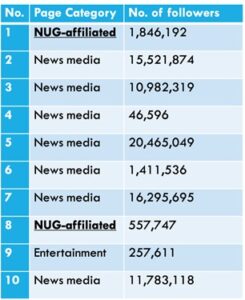

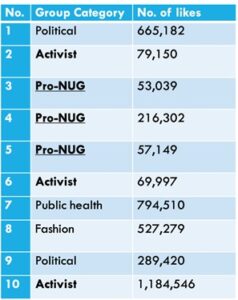

In contrast to pro-military content, most dissident content highlights resistance activities and military repression. It is also relatively prevalent among coup-related Facebook posts, being shared by various types of mainly political and news-oriented pages and groups. Two NUG-related pages are among the top 10 pages with viral posts. Six activist groups, three of which are NUG-related, are among the top 10 groups with viral posts.

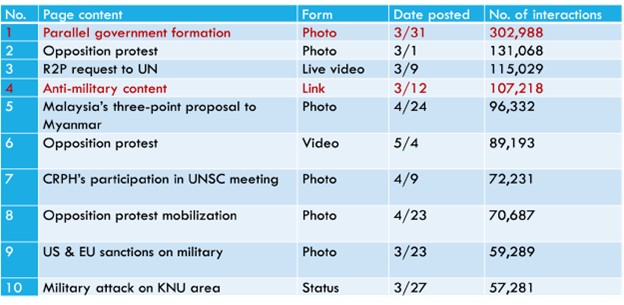

As a result, dissident posts received an average of 1000 interactions. The most popular post was CRPH’s announcement that they would form a parallel government, with more than 300k interactions.

Table 1. Top 10 pages & groups with viral posts

Table 2. Top 10 viral page posts

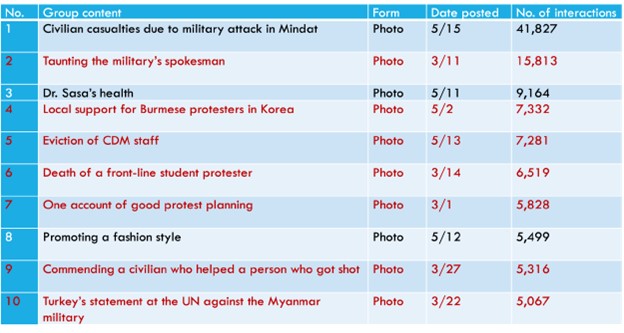

Table 3. Top 10 viral group posts

While dissident content generated more online engagement among Myanmar netizens overall, two additional trends warrant mentioning.

First, among dissident posts, content expressing support for democratic values or the parallel National Unity Government received less engagement on average than posts highlighting military abuses or general anti-coup resistance activities. Furthermore, among coup-related content, posts that mention military crackdown against activists received significantly more negative reactions than others. This suggests that there is more unity around contention against the military than support for any particular faction within the broader anti-coup movement, such as federal democracy or the NUG. As dissidents and ordinary social media users can broadcast scenes of military crackdowns and resistance to heighten popular grievances and facilitate coordination, this has likely led more people to engage in anti-coup activism. Authoritarian repression is more likely to backfire in the digital age.

The second trend is more unexpected. We find that the prevalence of activist content and engagement with this content on public pages and groups actually decreased over time while pro-military content and engagement increased. This could be due to one of two reasons: either decrease in public interest and support for activists, or the migration of activist content to private groups or other encrypted platforms like Telegram in order to avoid infiltration, monitoring, and arrest. Pro-military users, on the other hand, may have mobilised later and felt comparatively safer with protection from the military.

In short, the Tatmadaw’s disinformation campaign since the coup has neither managed to dominate social media nor significantly sway public opinion in its favour. Most netizens do not trust or support military propaganda. On the other hand, its conventional method of cracking down on activist content on Facebook, by arresting online users who were found to use VPNs or post anti-coup narratives, seems to have curtailed the influence of dissident voices over time. But for now, online content exposing military repression and broadcasting resistance activities continues to proliferate despite the threat of arrest. The widespread use of social media by dissidents in this recent episode of anti-military struggle has likely facilitated a civil disobedience movement with greater grassroots support than ever—a development that the Tatmadaw might find difficult to halt.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss