Simplistic arguments currently circulating in Thailand are in danger of neglecting the complexities of democracy and ignoring roadblocks to its ‘return’.

In the words of Winston Churchill, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time”.

Churchill’s statement contains some truth; democracy has been a relatively successful project within the realms of Europe, North America and Oceania. But democracy has yet to be fully established elsewhere. Most countries in Southeast Asia are not ruled democratically and this absence of tangible democracy is spurring an emerging trend that can only be described as ‘democracy worship’.

The people and groups leading this trend have glorified and simplified the basic principles of democracy, elevating the political system to cult-like status. Democracy is discussed and demanded as the instantly required form of government that a state must adhere too. At times individuals describe it, unintentionally and intentionally, as that of perfection and utopianism.

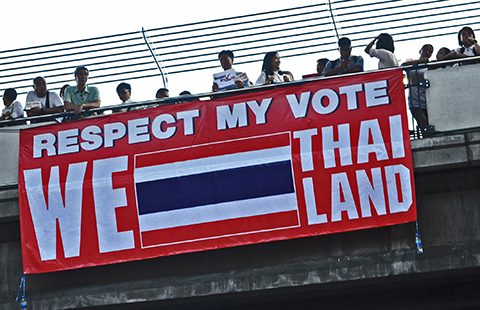

Examples of ‘democracy worship’ can be seen throughout Southeast Asia, however, it is most obvious in Thailand, where democracy is admired and given sacred qualities, with little thought given to the complexities or theory behind it. Equally as clear is the problematic nature of the country’s democracy or lack of it.

Such desire for democracy is valid as Thais have lived in a constant state of semi-democracy, constantly interrupted by aggressive coups, appointed prime ministers, and full blown dictatorships, forming a repetitive pattern that has reoccurred for decades.

Coup culture within Thailand has many distinct characteristics, with two standing out more than others; the worship of democracy within certain areas of society, and an almost blasé attitude towards military coups. Again, there are legitimate reasons for individuals to desire a ‘return’ to democratic governance. However, the simplistic arguments over the desire for democracy currently circulating in Thailand, are in danger of neglecting the complexities of democracy.

Social media, an understated instrument of political discourse within Thailand, helps to demonstrate democracy worship and the cult-like following that has been attracted by democracy’s ideals. The trend may also be enhanced through other forms of worship within Thailand, such as ‘academic worship’ and ‘professor worship’, which can give academics a cult following of their own, whether they like it or not. So-called ‘celebrity’ academics, either living in Thailand or based abroad for political reasons, are highly active in posting and promoting democracy related material on numerous social media platforms.

The majority of the time such posts contain little or no explanation of how democracy can become successful, or what the major obstacles to democracy are – particularly important given the complicated issues related to the balance of power and powerful institutions within Thailand. However, a single post can get over 10,000 ‘likes’ and be reposted hundreds of times. It is also common for these ‘celebrity academics’ to publish up to 10 democracy-themed posts per day, again, demonstrating the need for Thailand to return to democracy but offering no solutions, suggestions, or critiques of the more complicated issues.

Stark divisions and aggressive polarisation is endemic throughout all aspects of Thai society including: governance, the religious establishment, the supreme institution, the military, civil society, and educational institutions. The interconnectedness between networks of power in Thailand is multifaceted, complex and ingrained. Well-known academic Duncan McCargo coined the term ‘network monarchy’ to describe this complex web of interconnected power that holds up the country’s royal institution. By fusing itself to all aspects of Thai society, and spreading influence to all corners of the country, the monarchy has occupied a seat of supreme dominance and reverence in Thailand, entrenching its values to ensure its continued survival.

It is here, within the realm of ‘networks,’ that those who situate themselves within the cult following of democracy, or worship democratic principles, neglect to understand the intrinsically problematic nature of democracy in Thailand. A functioning democracy, adhering to democratic principles, cannot operate within a country that fosters such a complicated network of relationships, all attempting to receive, abuse or hold on to some form of power.

Arguably, these networks of power exist within democratic countries as well, particularly the United States. However, in the United States there are also independent checks-and-balances, reinforced by strong institutions, capable of limiting the means of those seeking to abuse power. These independent reinforcements have disappeared from Thailand’s political landscape.

The power and influence of the Thai military, which sits above all other forms of power, except the royal institution, needs to be completely dismantled. Speaking hypothetically as there is no possibility of this occurring any time soon, before democracy can become any more than a ‘desire,’ the military should be placed in civilian control and given little or no capacity for influencing power relations or promoting democratic ideals. In the future Thailand could take note from Indonesia and how it went about limiting the power and influence of the military.

The legitimacy that the monarchy, and thus in turn the military, receives due to their relationship with the Buddhist establishment, the Supreme Sangha Council, also needs to be understood as a significant road block to democracy. The Sangha is undeniably connected to the realm of long-established networks, and is constantly attempting to protect its members’ privileged position of power and reverence in Thai society.

With such a complicated and multifaceted network, democracy has many obstacles, as the old establishment will always be able to legitimise itself through the many sensitive and controversial aspects of the network, particularly religion.

Another major problem with democracy in Thailand is the issue of regional divides. So called ‘red provinces’ that have been branded as Shinawatra supporters, or endorsers of Thaksin-associated political parties, can boast growing populations and a larger voter base than those on the opposing side, or sides, of politics. Especially those whom are supporters of the old establishment.

If democracy does ‘return’ to Thailand, it is inevitable that those aligned with Thaksin Shinawatra would return to power with a majority of the vote, significantly threatening those aligned to more established power bases, such as the monarchy, military and the consumerist city-based elite. Such established power bases will not accept a threat to their power or loss of power, and will once again support and orchestrate a coup. The cycle will continue.

Those in Thailand who are unofficial members of the democracy cult continue to constantly and simplistically argue for democracy to return to the country. This is admirable at first glance, however with a more in-depth analysis, it is clear to see that democracy is impractical and will likely end in additional violence. Both Thai and foreign academics, journalists and civil society groups all argue for an instantaneous restoration of democracy in Thailand. What they fail to mention or discuss, is how? How does one take on the old establishment, a force that takes its legitimacy from the untouchable royal institution?

Members of the democracy cult or those who worship the idea of democracy need to redirect their attention to aspects of the so-called network power issue. They need to explain how balances of power need to change, the relationship between the military and the monarchy, the enormous division within the Thai population, and the relationship between the old establishment and elite and the monarchy and majority religion.

Worshippers of democracy who argue for instant democracy to take place within Thailand are also underestimating issues of systematic corruption that have plagued semi-democratic governments in the past. Although elections won by both Thaksin and his sister Yingluck were reasonably democratic, and inappropriately nulled, both governments struggled with corruption. However when it comes to corruption, the established elite are significantly more susceptible to its more dramatic forms; thus there is a valid argument behind those who argue that democratic governments foster less corruption.

Arguing for democracy is admirable and deserves respect, however to the extent it is promoted and discussed on social media and elsewhere, it is problematic. Democracy is not possible in Thailand anytime soon, and those who continue to contribute to ‘democracy worship’, do nothing more than demonstrate the lack of solutions and impracticality of democracy in such a fractured society.

It would do the democracy argument well if attention was redirected to tackling some of the larger issues that act as roadblocks to democracy.

Mat Carney is a research fellow and coordinator at the Centre for ASEAN Studies at Chiang Mai University, an independent blogger and ANU graduate.

Emily Donald is an intern at the Labour Rights Promotion Network in Thailand and undertaking her studies at the University of Queensland.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss