From ribbons, to elections and ceasefire, what will change Myanmar’s long reliance on armed forces?

A short time ago, if you can recall a time before the 8 November elections, staff from Myanmar’s Ministry of Health brought considerable focus to the role of the military in government through a black ribbon campaign.

They sought to raise awareness on the impending appointment of military officers, without formal medical training, to the ministry.

The campaign was an immediate success, particularly on social media, with a reported 40,000 ‘likes’ on Facebook in just three days. Its momentum led to a yellow ribbon campaign against military appointees to the judiciary, a red ribbon campaign for the Ministry of Energy, a blue campaign for electrical engineers, and a green campaign for education.

While this was not the first time Myanmar’s ruling party had sought to bring military personnel into government, the response represents one of the first open and peaceful campaigns against such moves in recent times. It also provides an excellent starting point for deeper examination of Myanmar’s culture of militarisation.

Before a military coup

For many, the most visible form of militarisation are the armed forces personnel who currently comprise 25 per cent of Myanmar’s Union and State parliaments — a product of the 2008 constitution that was put in place after a succession of military-based ruling bodies took power in 1962.

But Myanmar has always been a highly militarised country, even before outright military rule and the rise of ethnic insurgencies. In The Union of Burma, Hugh Tinker notes this could be seen as far back as 1959:

Burmans take pride in the military traditions of the past. Under the Kings the basis of society was not so much the village in which a man lived as the regiment to which he belonged…Up to quite recent years villages in upper Burma have been known as myin, cavalry, or thenat, musketeer (p 312).

In this sense, it comes as little surprise to observe the use of military strategies among communities themselves, typified by the use of landmines to protect their resources from the Tatmadaw and other Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAO), militia and Border Guard Forces (BGF), as well as new businesses entering their areas.[i] The level of militarisation among a population that has been in conflict for 60 years cannot be underestimated.

Another key part of this historical culture is a functioning network of patrons mostly consisting of the political elite with an available force of the population under arms.

An example of this is when King Thibaw, in 1185, failed to rally his armies from around Burma to protect Mandalay in time against the British. The remaining Royal armies and a network of rulers and commanders retained their arms and took to a form of guerrilla warfare. In response, the British military force was expanded to over 16,000 persons (as noted by Mary Callahan in her book Making enemies).

While, mostly excused as a way in dealing with dacoity, or banditry, the Burmese forces were essentially militia units of guerrilla freedom fighters funded by contemporary elites.

Post-independence to 1962

The patron-client basis of militarisation is also evident in the immediate period after World War II, in the interplay between military and political leaders for state dominance (see Callahan’s Making enemies). Militia played a role in conflict between central Burmese military control and ethnic aspirations for self-determination. There were also many local politicians and elites who used their positions to form their own militia (as noted by Callahan in Making enemies).

One notable example of this period are those members of the Burma National Army (BNA), headed by General Aung San, who chose not to take part in the post-independent army, but instead to become part of the para-military unit, The People’s Voluntary Organisation (PVO). Mostly described as a welfare organisation, the PVO was available to ensure that ruling authority was enforced locally.

And as Tinker notes in The Union of Burma:

It is also necessary that the present delegation of powers to semi-political, semi-private authorities shall be terminated. There are too many weapons in the hands of persons over whom the Government has only the loosest control, and too many bosses who can bring influence to bear upon the administration and society…Until the Government can command the uncertain loyalties of these ex-rebels, it will always be vulnerable (p 60).

It was a dramatic time, and by 1962 the Tatmadaw emerged as a central force in the country. Leading nationalist, U Nu, described this moment as a, “development period”, [for forming an army] “that went from being stooges…at the beck and call of this or that organisation into dependable custodians of the constitution.” (Quote from Tinker’s The Union of Burma.)

2010 elections

More recently, local militarised groups known as people’s militias were included in the 2008 constitution.[ii] Their power mostly exists in networks extending among politicians, military, and businesses. These provide access to the formal or informal economy, or sometimes both.

As Callahan and Mark Duffield have shown, broad networks of patronage exist in Myanmar that have created a series of political accommodations for militia groups at sub-national levels, including, business concessions and other incentives. Most notable is the recent Global Witness report that reveals implicit relationships of business, government and ceasefire groups in the informal economy around the semi-precious stone, jade.

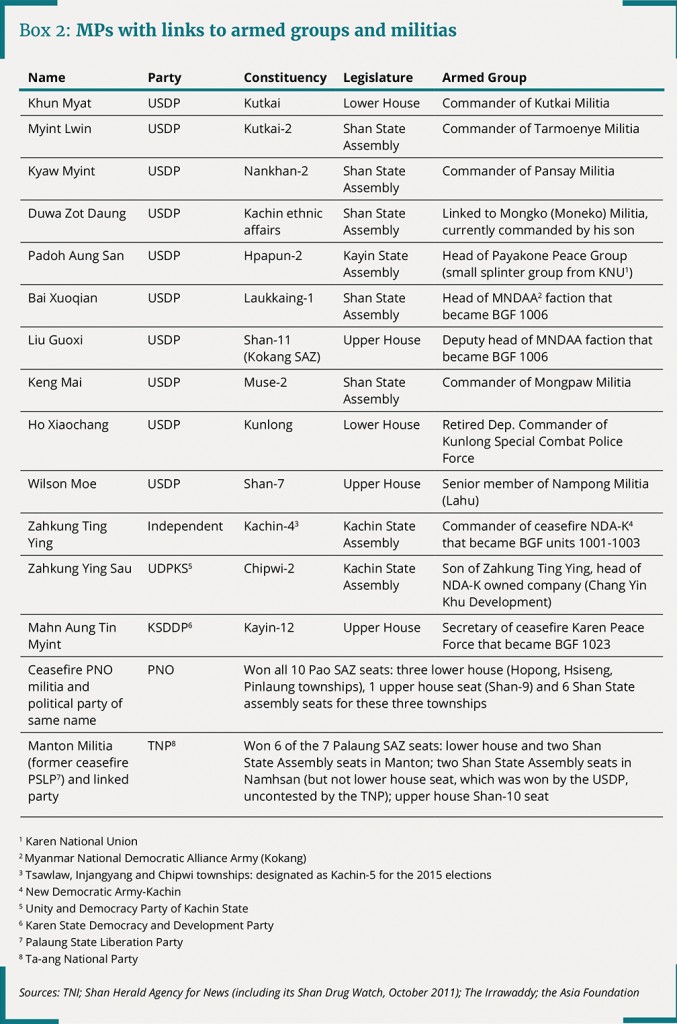

In the lead up to 2010 elections, militia were requested to make the transition to Border Guard Forces under a Tatmadaw command structure. While this led to various forms of accommodation between the government, Tatmadaw and militia, it also resulted in 15 elected Union and State/Region politicians with direct links to militia.

Source: Myanmar Policy Briefing, 16 September 2015, Ethnic Politics and the 2015 Elections in Myanmar.

In early analysis from the 2015 election results, four of those listed above, U Khun Myat, U Myint Lwin, Duwa Zot Daung and Keng Mai, retained their respective seats.

Dealing with militarisation from within the National Ceasefire Agreement

What is clear is that the militarisation of Myanmar did not begin with ethnic armed organisations and will not be fully resolved by elections and a National Ceasefire Accord (NCA).

While the NCA remains a significant tool for bringing security to local communities, we should not underestimate the reticence of actors to change a functioning and dysfunctional network of the political economy.

It is critical that consideration be given for militia, BGF, Tatmadaw and their local patrons to re-imagine the structure of political economies going forward; economies that have been tentatively opened by ceasefire negotiations and elections. It is too early to say if the NCA has the ability to fully unlock networks whose very existence have been framed by the right for ethnic determination, itself engrained in generations of military resistance.

However, one way to ensure these discussions can occur is to build a joint monitoring mechanism that acknowledges the existence of localised manifestations of militarisation. Many of the EAO commanders exist daily alongside local BGF and militia, whose lives have been normalised with a history of grievences and economic jealousy that have existed within a state of continual insecurity as the status quo.

An ineffective NCA could greatly weaken the role and legitimacy of EAOs relative to militia and BGF, who have unilateral and occasional territorial agreements that are not subject to monitoring or international interest.

For example, what if a local BGF grabs community land to build a camp, or a rubber plantation? How will communities or EAO respond under an NCA? What if it’s in a NCA area with mixed Government and EAO/BGF administration? The response of communities in the past has been to engage patrons from EAO to religious leaders in order to negotiate, while resorting to the use landmines for protection in the meantime.[iii]

While a parallel process of ceasefire monitoring and political dialogue is included in the NCA, the trust built through a broader monitoring process would promote acceptance of political dialogue. Security allows time for a sense of legitimacy to arise among stakeholders in political dialogue.

A most notable first step could be acknowledging the administrative capacities and the involvement in local economies, formal or informal, in areas under the control of these various actors.

Further, support from international agencies that give consideration to local historical, cultural and economic contexts are more likely to promote a local political space and the emergence of representative decision-making.

To focus exclusively on bringing development into areas as soon as possible is likely to place pressure on early joint monitoring tasks, jeopardise trust, and reinforce learnt militarised responses from a range of groups, including communities.

That is why the push for large-scale development and poverty reduction extending Naypyitaw’s administration in areas controlled by EAO and militarised actors is so concerning. It potentially undermines joint monitoring and the political credibility needed to build strong inclusive local dialogue.

A more credible approach would direct much needed international community development support to building negotiation capacities of local militarised actors and promote their participation in legitimate institutions that can engage communities in solving local issues. Building capacities through inclusive and participatory engagement will go far to overcome the exclusion of those who have for so long been outside of political dialogue and decision-making processes.

In this way peace becomes more than socio-economic development, more than poverty reduction or improved self-sufficiency; it is the engagement of actors in local political processes to determine their political and socio-economic direction.

This is crucial. Militarised actors will need time to adjust from a political military environment that has produced uncertainty, insecurity, and fear to one that can offer space to build trust with local communities.

Dialogue on topics such as self-determination, ethnic rights, and decentralisation can only be realised if existing or legitimate institutions can emerge at a sub-national level that give space for local decision-making on the roles of militarised actors while allowing non-military responses to come to the fore.

Bringing BGF and militia into political dialogue with communities at a sub-national level will be critical to this success. Furthermore, the financial investment of militia and BGF in the informal economy could be analysed to see how parts of this economy can be formalised before attempts to reintegrate armed persons into a nascent rural economy occurs (this is also noted by Callahan in Making enemies).

At this early stage, considerable focus will need to be built between all actors, including militia and BGF before discussions on the militarised nature of Myanmar’s political power can be undertaken. The NCA provides the potential to re-imagine social military relations among the Tatmadaw and EAO, and their communities.

It also provides the possibility to re-formulate local militarised networks that have until now accommodated mostly informal economies. Leaving ceasefire and political dialogue open for the involvement of BGF and militia will go a long way to ensure sub-national agreements and their resulting policies reflect realities in local decision-making.[iv]

The key question is; how do we re-imagine networks of patronage and influence that can sustain a fragile ceasefire through early monitoring, and in a way that can strengthen social and cultural ties, so that militarised decision-making doesn’t build tension and renewed conflict?

Gregory Cathcart is an international development consultant focusing on community perspectives regarding landmine/unexploded ordnance (UXO) related issues in Southeast Asia.

ENDNOTES

[i] MRE KAP Report: UNICEF 2015, unpublished, 22 per cent of respondents reported landmines keep their village safe.

[ii] Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, 2008, “With the approval of the National Defence and Security Council, the defence Services has the authority to administer the participation of the entire people in the security and defence of the Union. The strategy of the people’s militia shall be carried out under the leadership of the Defense Services.”

[iii] MRE KAP Survey: UNICEF 2014, unpublished

[iv] Call C, 2012 Why Peace Fails: The Causes and Prevention of Civil War Recurrence, Georgetown University Press.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss