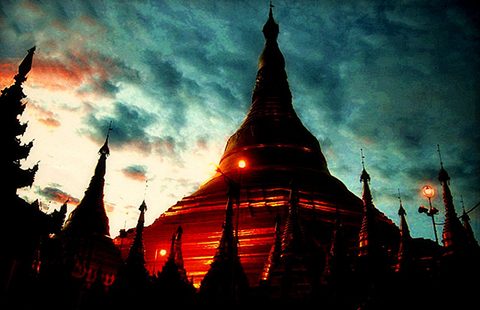

Photo: Jose Javier Martin Espartosa on flickrhttps://www.flickr.com/photos/druidabruxux/

Country must overcome economic challenges, ethnic conflict and entrenched military attitudes to ensure a stable future.

Earlier this year I was fortunate enough to be part of the Australian National University’s first study tour to Myanmar.

I hopped on the plane with a single question: where is the country’s democratic transition heading?

There is vigorous debate over whether Myanmar is working its way towards democracy or sliding backwards. Before my departure I read a range of predictions. But how can we tell who is right?

Scenario development offers a handy way of tackling such questions.

It acknowledges that while we can’t predict the future, we can identify powerful uncertainties. By examining how these might interact with and influence Myanmar’s democratic transition, we can develop a range of possible scenarios for the transition process.

By the end of the trip I was convinced Myanmar faces three critical uncertainties: the economy, ethnic conflict, and military attitudes.

Economy

Myanmar borders 40 per cent of the world’s population. According to Mr Moe Kyaw from the National Economic and Social Advisory Council, this potential for trade presents a major opportunity. He was enthusiastic about Myanmar’s potential, arguing GDP growth could reach 10 per cent a year.

But challenges to economic growth persist, such as poor infrastructure, monetary policy, and access to credit.

During our visit to the International Finance Corporation (IFC), officers said the local business community had high hopes for economic growth in the early stages of Myanmar’s opening up. However, those hopes have decreased over the last few years.

While a recent IFC survey indicates an uptick in local business optimism over the medium-term, the officers described their sense of economic stagnation. Whether Myanmar’s economy might grow, stagnate or shrink is thus deeply uncertain.

Ethnic conflict

During our tour government actors voiced their desire to see Myanmar’s long history of ethnic conflict resolved.

The Defence Minister Wai Lwin told us the military “wants peace the most”, and spoke about their sacrifices made in dealing with the conflicts. Similarly, the Myanmar Peace Centre told us about the numerous parliamentarians who are genuinely committed to conflict resolution.

However, major roadblocks remain.

For example, a key demand from ethnic armed groups is for a federal state. Those involved in negotiations have different views on what this might mean in practice. Unsurprisingly, the military remains strongly opposed.

The Defence Minister argued discussions of a federal state are a major cause of instability and state rights to secession under the 1947 constitution is the main barrier to resolving conflict.

Another obstacle lies in economic incentives. In Naypitaw I spoke with several MPs, including U Win Htein from the National League for Democracy. He argued several armed groups are not genuinely invested in the peace process.

Instead, groups remain interested in the conflict due to their financial interests in drugs, jade or teak. Whilst these interests endure, it will be difficult to build lasting peace.

This point was underlined by Dr Banya Aung Moe from the All Mon Regions Democracy Party. He told me how he worked in the jungle as a doctor for the Mon armed rebellion for seven years and that the group ultimately disarmed when they felt their interests were best served from working within the political process.

Giving people incentives to put down arms and “leave the jungle” is vital to conflict resolution. This remains a formidable challenge.

Military attitudes

Lastly, there is the question of the military and its perceptions of democracy. As we witnessed in our meeting with the Defence Minister, the military strongly believes that their parliamentary presence is crucial for national stability.

Although he acknowledged Myanmar’s democratic transition is “nowhere near satisfactory”, he believes the military’s current 25 per cent parliamentary presence is important for gradual change. In future, he said the military expect to reduce their parliamentary presence, but not until stability is achieved.

Interestingly, we met a number of ‘liberal’ commentators who suggested another five-year period of the current parliamentary arrangements improved the long term prospects of Myanmar’s democratic transition.

This surprising perspective raises a question regarding the extent of public support for the military’s political role.

Anna Peterson with local university students. Photo: James Walsh.

University students I spoke with felt that the military was unlikely to reduce its presence in the short to medium term, and in fact, might increase its dominance. Two considerations support this pessimistic perspective.

First, as Marcus Mietzner has argued, the military’s involvement is crucial to a country’s first post-authoritarian government. The greater its influence, the more likely the military is to protect its power and resist reform.

Second, as things currently stand, the military has used its power to prevent, for example, increased transparency over its military-business complex. Once again, outcomes in this space remain uncertain.

As my plane left the runway in Yangon, I realised although I had identified some critical uncertainties, a bigger task remains.

This involves identifying the various ways in which these uncertainties might interact and shape Myanmar’s democratic transition.

Key questions in this space include will economic growth increase the chances of successful democratic transition? How might the military and society react if Myanmar’s economy goes through the floor?

Could economic stagnation trigger an internal military power struggle between those in support of democratic transition and those opposed? And does continued ethnic conflict necessarily obstruct democracy?

When it comes to predicting Myanmar’s future, there are clearly as many questions as answers.

Anna Peterson is studying a Masters of Asia-Pacific Studies at the Australian National University. She recently completed the ANU course ‘The Political Economy of Myanmar’, convened by New Mandala co-founder Andrew Walker.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss