In March 2022, Muhammad Qodari, the high profile executive director of Indo Barometer survey institute grabbed headlines by proposing that President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) and his former presidential rival and now Minister of Defence Prabowo Subianto run on a joint ticket for the 2024 presidential election. He argued that this would unify the nation and “polarisation would disappear”.

Politicians and scholars have repeatedly warned of the dangers that polarisation, especially of a religious nature, poses to Indonesian democracy. Deepening cleavages between religious communities that were once on civil terms are seen as contributing to a political culture of intolerance and democratic illiberalism.

But in the past three years, a new trend has emerged which might best be labelled “counter-polarisation”. In this development, politicians and their parties undertake initiatives or manoeuvres in the name of reducing polarisation and easing intra-communal tensions. This usually involves parties that were once on opposing sides of the political divide agreeing to cooperate or coalesce. Not uncommonly, this is hailed as a move to restore national cohesion and strengthen democracy.

The first and most striking example of this was the decision of Prabowo Subianto, the losing candidate in the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections, to join Joko Widodo’s new cabinet in October 2019 as Defence Minister, despite having campaigned sometimes rancorously against his rival. One of Prabowo’s justifications for this abrupt about-face was the need to heal divisions between his and Jokowi’s supporters.

Since then, similar arguments have been used to broker deals that bring together seemingly disparate electoral candidates or parties. One such case is Qodari’s proposed Jokowi-Prabowo joint ticket, which proved especially controversial because it would require a constitutional amendment to allow Jokowi to stand for a third term. Critics said changing the constitution for this purpose would be democratically regressive. Qodari argued that so great was the threat of polarisation that extending the presidential term limit was justified. Another proposal called for Prabowo, who previously drew strong Islamist support, to run with Puan Maharani, from the nationalist Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P). In the same spirit, the chairman of the NasDem party suggested that Ganjar Pranowo, the Central Java governor who represents the nationalist camp, take as his running mate Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan, who attracts strong Islamist support.

Jokowi-Prabowo political reconciliation as Javanese strategy

The underpinning politics between Jokowi and Prabowo reveals a deeper complexity within the Indonesian election.

Parties also used “bridge building” arguments to support a flurry of new alliances and proposed coalitions. Two Islamic parties—the United Development Party (PPP) and the National Mandate Party (PAN)—coalesced with the nationalist Golkar in May 2022, and more recently the Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), launched alliance talks with the religiously neutral NasDem and the moderate Islamic National Awakening Party (PKB), both of which were previously staunch PKS rivals. Even debate over the length of the 2024 election campaign saw parties arguing about whether a shorter period was more likely to reduce polarisation than a longer one.

Two questions arise from these developments. Is polarisation as serious a problem as many contend, particularly following the 2019 elections? And is the use of counter-polarisation justifications for political realignments credible or just a cover for other motivations? We will argue that a recent survey shows a decline in the high levels of polarisation of the 2014-2019 period and that much of the counter-polarisation trend is driven by parties’ attempts to maximise their opportunities in the run-up to the 2024 elections.

How Polarised is Indonesia?

This article draws from two data sets, both from Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI). The first is the “National Survey on Polarization” conducted in April 2021, which involved 1620 respondents across all provinces of Indonesia. The margin of error was +/-2.5 at a confidence level of 95%. The second is “Polarization among Indonesian Muslim Elites”, an analysis of social media content between 2016 to 2021. More than 2000 excerpts and quotes from a wide range of Muslim organisations and leaders were analysed to discern whether the postings represented conservative, progressive or neutral viewpoints on controversial current issues.

The survey found that 11% of respondents felt Indonesia was highly polarised and 27% thought it was quite polarised, compared to 33% who believed there was only slight polarisation and 16% who saw no polarisation. This suggests that for a majority of the public, polarisation was not a significant national problem. Those who thought that polarisation was of concern belonged primarily to the elite in urban areas: professionals, and those with higher levels of education and income. Thus while over 56% of those with tertiary education thought that polarisation was of concern, less than 20% of those with only elementary education believed it was a problem. This indicates that existing polarisation is more an elite than a grassroots concern.

In addition, 46% of respondents who use the Internet (64% of the total number of voters) also tended to see the country as highly or quite polarised, compared to only 24% of respondents who have no Internet access. Thus, although in general the respondents feel that Indonesia is not polarised, exposure to the Internet, such as social media or news sites, increases this perceived sense of division.

A recurring theme of the “reducing polarisation” proposals is that there is a deep cleavage between those holding pluralist views and those with Islamist views. Pluralism in this case refers to those who favour a polity based on inclusivity, in keeping with the principle of religious neutrality set out in the state ideology of Pancasila. Pluralists resist special privileges being accorded to the nation’s large Muslim majority and also object to political mobilisation based on what they see as “transnational” Islam, or an expression of Islam perceived as inspired by movements or trends from the Middle East. Islamists are those who seek a political and social system in which Islamic law and principles feature prominently. They believe that the majority status of Muslims combined with Islam’s important role in Indonesia’s history should be formally reflected in the structure and laws of the state.

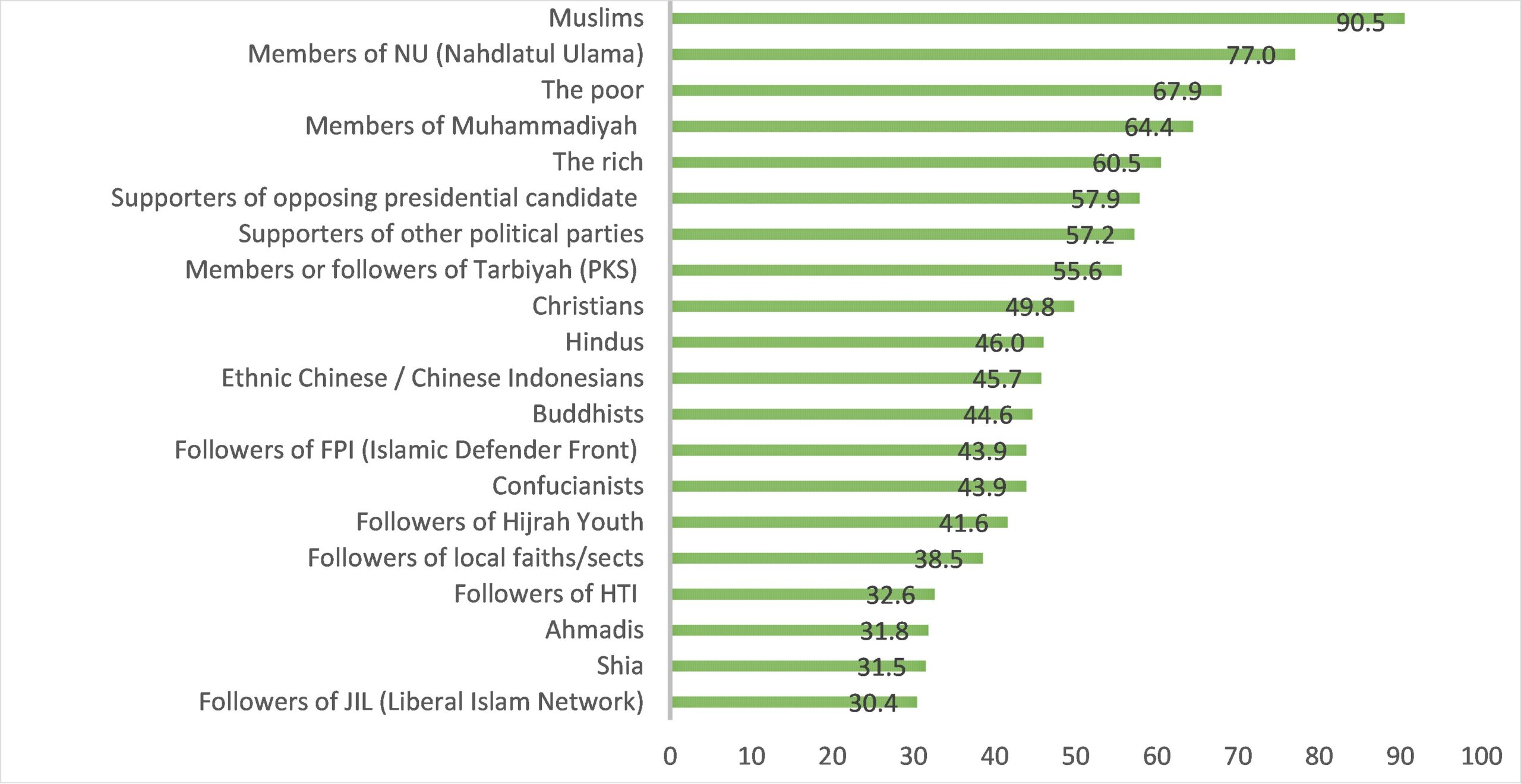

The LSI survey, however, showed that the cleavage between pluralist and Islamist groups is less deep than widely supposed. Indeed, the results suggest that high public antipathy is mainly directed to specific religious minority groups rather than major ideological blocs. The survey used the “feeling thermometer” method for measuring polarisation. Respondents were shown a list of organisations and parties and asked to rank these according to how warmly or coolly they regarded them, with 100 being hot and zero cold. (see Chart One)

Chart One: Feeling Thermometer for persons and groups

Of the numerous Islamist organisations included in the list, perhaps the most significant for measuring polarisation is PKS. This largest of Islamist parties that has garnered roughly 7-8% of the national vote in the four general elections since 2004 and is often singled out by pluralists as an example of “transnational Islam” due to its historical links to Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. PKS was a key Prabowo supporter in the 2014 and 2019 elections, spear-heading damaging social media and mosque-based attacks on Jokowi’s religious credibility.

Despite its reputation, PKS received an unexpectedly warm 56 “degrees” on the thermometer, placing it above the median. By way of comparison, the groups which were most warmly regarded were, not surprisingly, Indonesia’s two largest mainstream organisations, Nahdlatul Ulama (74) and Muhammadiyah (64). PKS was more warmly regarded than various non-Muslim groups, such as Christians (50), Hindus (46), Buddhists (43), all of whom might also have been expected to have cooler responses judging by earlier thermometer surveys.

So, if PKS drew mildly warm “feelings”, which groups evinced the coolest responses? The five lowest-ranked groups were: local faith sects (38 degrees), usually a reference to heterodox Muslims groups (sometimes referred to Kepercayaan or Kebatinan); the banned Islamist movement Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (33); the Muslim minority sects Ahmadiyah and the Shia (both 32); and, at the very bottom, the progressive Liberal Islamic Network (JIL) (30), which has been inactive for many years.

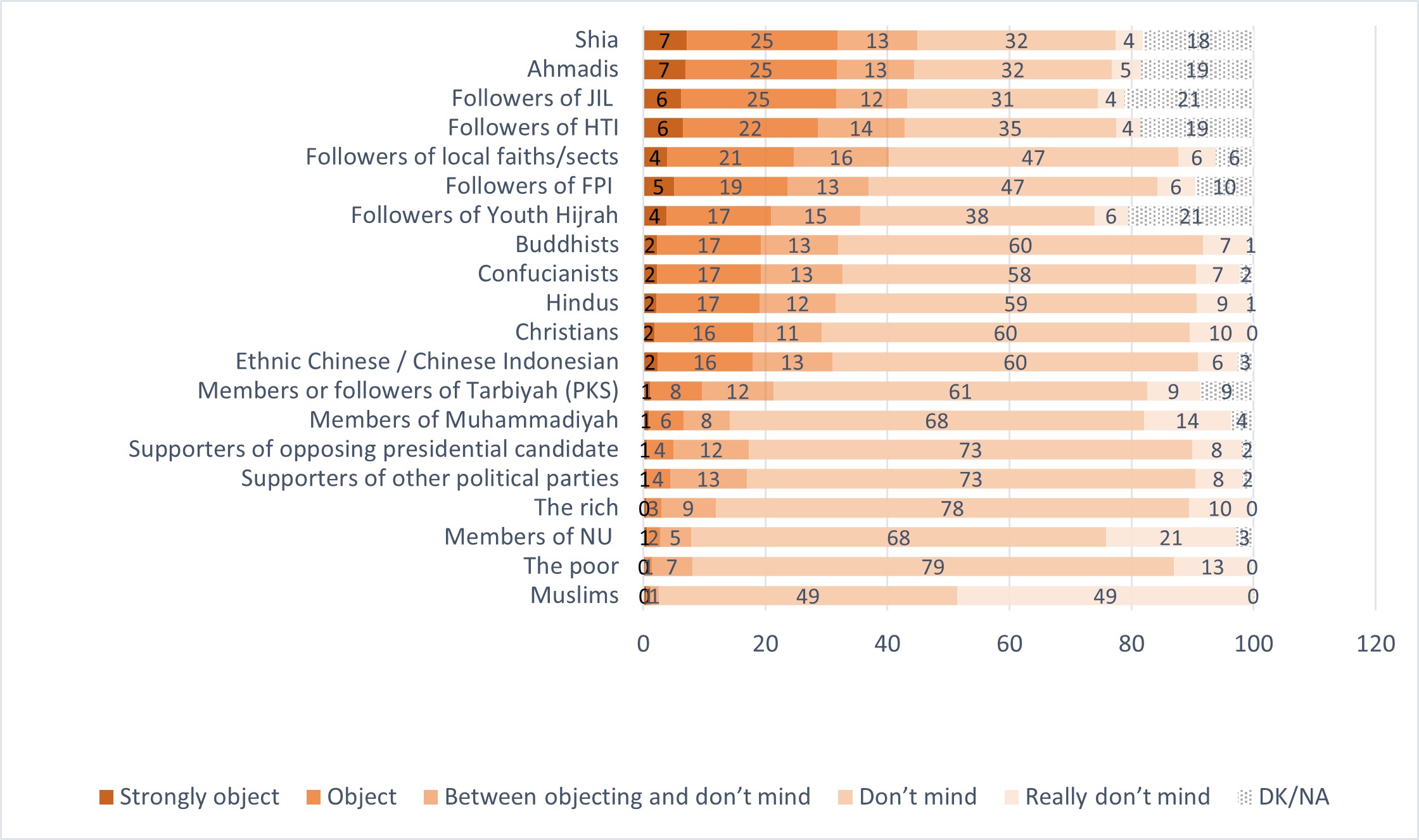

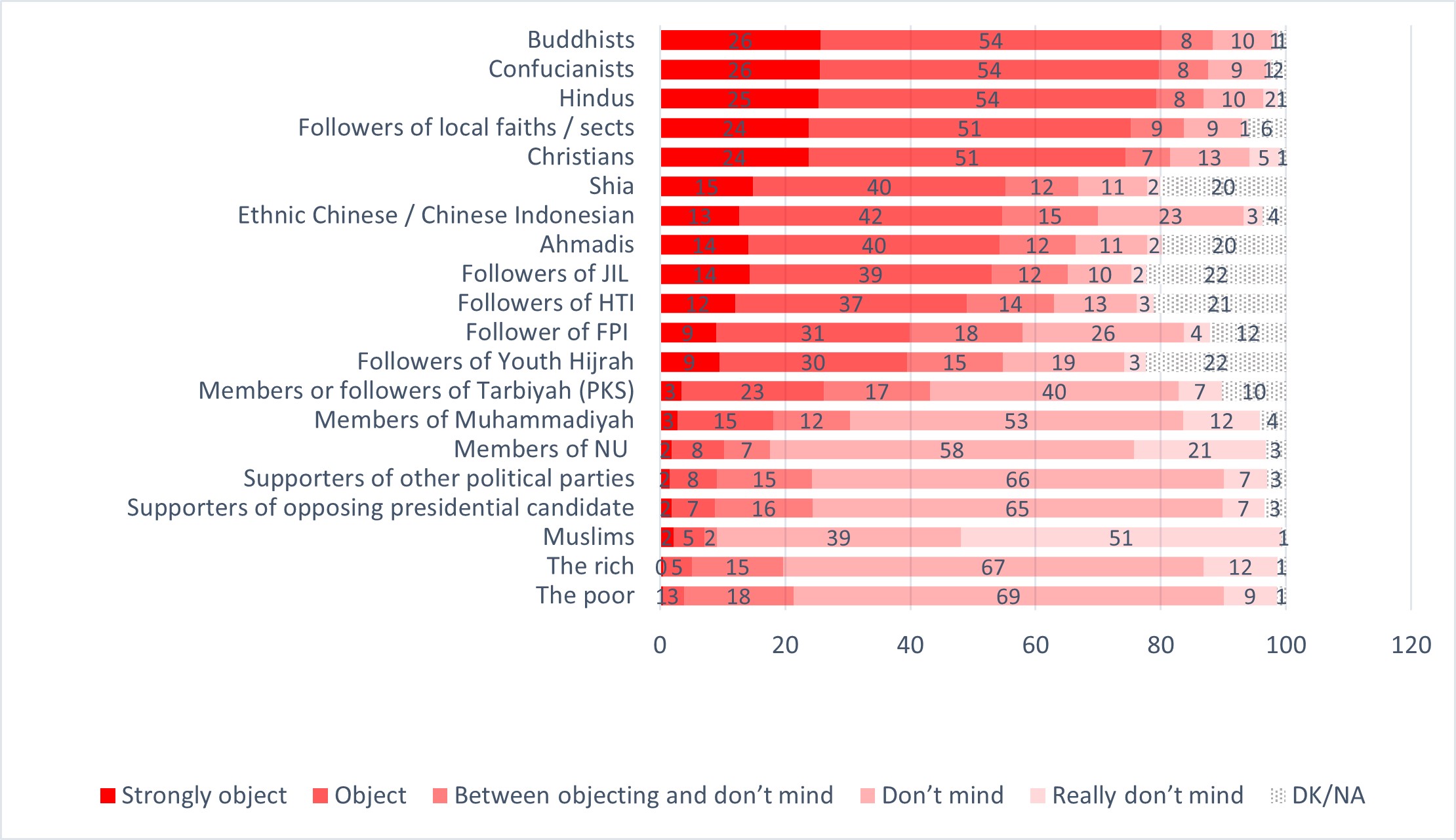

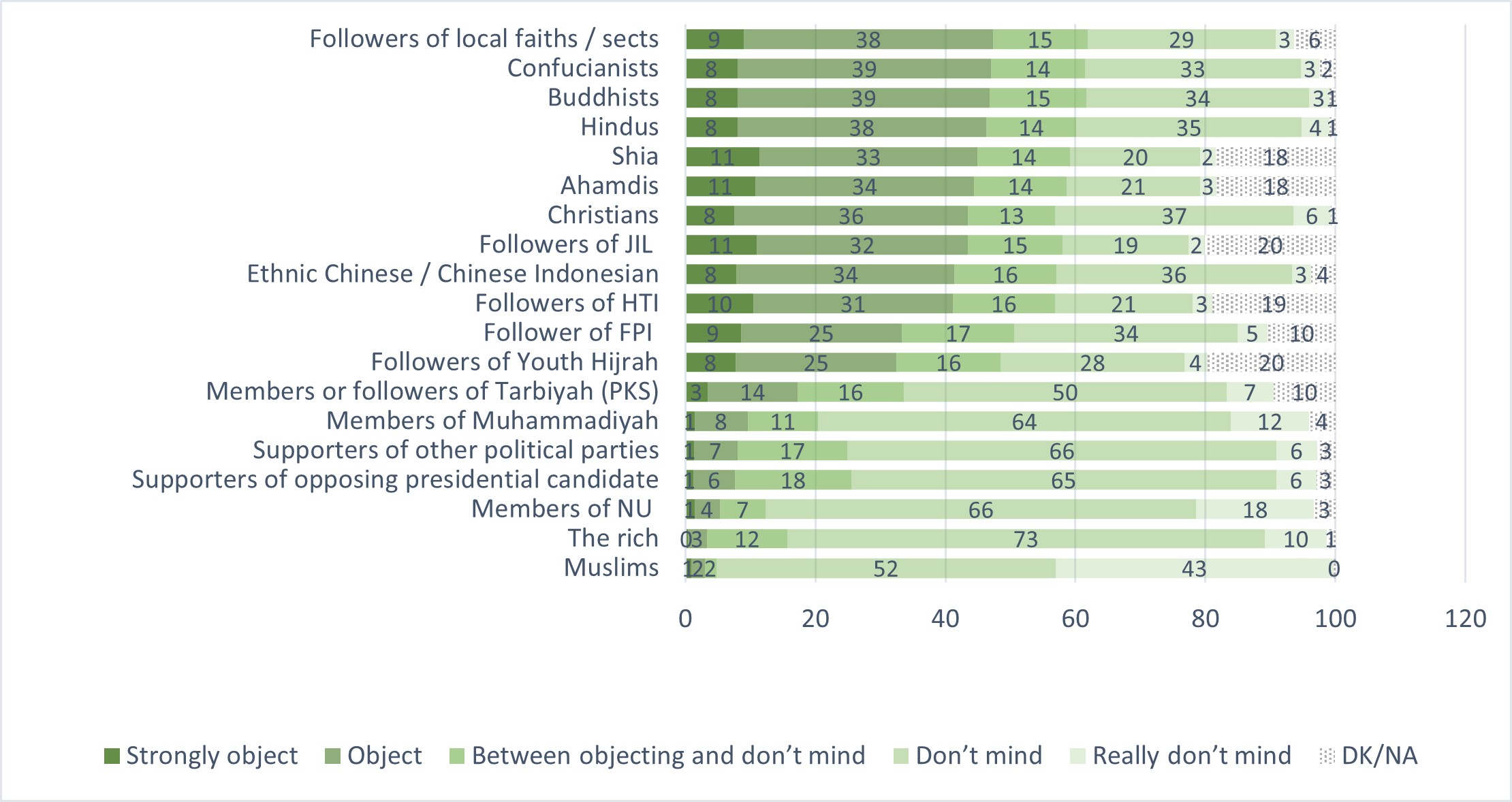

In addition to the thermometer questions, respondents were asked how they felt about having neighbours (Chart Two), sons- or daughters-in-law (Chart Three), or local leaders (Chart Four) from the same list of groups. This is a more specific measure of “affective polarisation’ that gauges the strength of positive or negative emotions. Once again, PKS drew less hostile responses than pluralist discourses might suggest. Sixty-nine percent of respondents didn’t mind having PKS members as neighbours and only 9% objected; 51% could accept them as local leaders and 14% were opposed. 47% of respondents would not object to PKS in-laws, though 26% were resistant. By contrast, more than 30% of respondents were opposed to Ahmadi, Shia or JIL members living near them, and HTI and the banned Islamist vigilante Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) attracted objections from 28% and 24% respectively. Forty-seven percent of respondents would not vote for candidates from local sects; 45% felt the same about Ahmadi candidates, 44% for Shia and 43% for JIL. Objections to having these same groups marrying into respondents’ families were especially high: 55% for Shia, 54% for Ahmadis, 53% for JIL, 49% for HTI and 40% for FPI.

Chart Two: Feeling Objection for being neighbours with…

Also notable was the fact that 81% had no objection to supporters of a rival presidential candidate or party for whom they voted living in their neighbourhood, which points to tolerance of political differences in contrast to strong dislike for religious outliers.

Chart Three: Feeling objection to marrying your child to…

Chart Four: Feeling objection to voting for a local leader who is…

These results reveal that the strongest feelings of dislike are directed not towards rival mainstream groups but rather at those on or near the margins who are seen as religiously “deviant” or “excessively” Islamist or liberal. Intolerance of Muslim groups that deviate from Sunni orthodoxy, as defined by the Ministry of Religious Affairs, the state-sanctioned National Ulama Council (MUI) or pre-eminent Islamic organisations, such as NU and Muhammadiyah, has been growing since the Yudhoyono presidency in the late 2000s. Local sects are frowned upon for their heterodoxy, particularly in blending Islamic and non-Islamic practices. Ahmadis and Shia, while regarding themselves as Muslim, albeit not part of the Sunni majority, are seen by many conservative Sunnis as theologically problematic and have faced repeated calls for their banning. HTI is disliked because it espouses the creation of a transnational Islamic government under the leadership of a caliph, which is seen as subverting Indonesia’s foundational principles. FPI has a public reputation of violence and contempt for law and order. Last of all, JIL, though long moribund, is still seen as emblematic of disruptively progressive ideas that undermine established Islamic norms and practices. In effect, by objecting to groups such as these, respondents are marking the boundaries of what they regard as acceptable mainstream behaviour. One might call this a centrist orthodoxy which seeks to exclude ideas and practices that do not conform to an increasingly rigid set of middle-ground norms.

The extent to which PKS is widely accepted as a mainstream party and its Islamism as part of the tapestry of Indonesian Islam rather than an ideological or religious “other” is also reflected in respondents’ answers to a question asking them to place themselves along a continuum of proximity to PDIP at one end or PKS at the other. While, as expected, feelings of closeness to PDIP are much higher than those towards PKS (18% vs 5%), nonetheless, 38% of those who answered the question placed themselves in the middle of the continuum.

Whereas the survey provides a snapshot of general community attitudes, social media content analysis offers insights into elite opinion because most of the material studied in this process comes from official websites of Islamic organisations or directly from individual Muslim leaders. One conclusion from this material bears out the findings of the “National Survey on Polarization” survey finding noted earlier, that elites are more polarised than the rest of society. For example, we can almost directly compare the survey results and the content analysis on the issue of the banning of FPI. With the former, 63% of survey respondents who were aware of the ban supported it and only 29% were opposed, but in social media, 50% of postings opposed the ban and only 34% were in favour. So, opinions were roughly reversed, with almost two-thirds of the general populace favouring the ban but only one-third of elite opinion supporting it.

Elite disapproval on deviancy issues also appears much stronger than the public’s disapproval. 62% of commentary in social media was hostile to local beliefs, 57% was critical of Ahmadiyah and 39% critical of Shia beliefs.

One reason for elite susceptibility to polarisation is that they are directly involved in competition for political and economic resources, which requires them to mobilise their support bases. Exploiting religious identity issues is often an effective means of generating emotion and commitment to their cause. By contrast, ordinary voters are not usually direct beneficiaries of contestation for political power and rewards.

The data presented above shows that polarisation, particularly on religious issues, remains significant, though not as serious as many politicians and observers have contended. If we place the 2021 survey results beside data from other credible surveys over the past decade, it is possible to conclude that the high point of polarisation occurred during and between the 2014 and 2019 elections, but has since declined.

While it is welcome that politicians have expressed concern about religious cleavages and shown a willingness to ease divisions in the name of national cohesion and protecting democracy, there are grounds for doubting that counter-polarisation is the real reason for many recent political manoeuvres. Prabowo readily used divisive appeals as a major part of his presidential campaign strategy in 2014 and 2019, and his main reason for now joining his former opponents is that he wants to rebrand himself as a unifying and statesman-like public figure for the 2024 election. The efforts to extend Widodo’s presidential term are driven by the desire of parts of the ruling coalition to remain in power as long as possible. Any extension beyond 2024 would be a further blow to the quality of Indonesia’s democracy. Finally, those parties that now find virtue in collaboration or coalition with former foes are motivated by a desire to maximise their negotiating positions in the run up to the next parliamentary and presidential elections. Putting together alternative tickets for the presidency reduces their risk of becoming peripheral players who have to accept what the largest parties dictate, rather than being able to protect their own interests.

The salience of polarisation may increase again in the led up to the 2024 elections. But we need also to be mindful of the fact that a certain degree of polarisation is normal in a democracy, a reflection of ideological difference and engagement with the political process. As Robert B Talisse reminded us recently, “The response to polarisation cannot involve calls for unanimity or abandoning partisan rivalries. A democracy without political divides is no democracy at all.”

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss