On 14 February Indonesians did not only elect a new president, but also 580 members of the parliament, the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR).

The first four post-Suharto parliamentary elections were subject to great scrutiny, being scheduled months before the appointment of the president (in 1999) and the direct election of the president (from 2004). But as a result of a 2013 Constitutional Court decision, both legislative and presidential elections have been held on the same day, all but ensuring that interest in the DPR elections has been buried in the avalanche of attention on who would prevail in the presidential polls.

The composition of the DPR elected in February will nonetheless be a critical factor for the stability and success of the incoming Prabowo administration. The balance of power amongst the parties in the parliament will be a major factor determining the composition of the incoming president’s cabinet. The parliament can potentially be a check on the executive power of the president and his fiscal initiatives, as well as an instrument for contesting his legislative program.

This article provides an overview of the 2024 DPR election results, focusing on the similarity between this result and that of the 2019 election. In 2024, voters supported the same parties in largely the same proportions as they did in the last election. With a couple of exceptions, the parties have maintained their bases of support, while failing to break into any new electoral ground.

I argue that the outcome shows that each of Indonesia’s parties has consolidated a base of support, despite an apparently low level of party identification amongst voters. I conclude that the party system has solidified and that simultaneous presidential and DPR elections have strengthened the trend towards a two-track electoral competition, with the presidential elections becoming a “air war” between national leaders and the DPR elections a “ground war” between parties at a localised level.

Social bases versus coat tails

We can sort Indonesia’s nine parliamentary parties into two main categories. The first consists of six parties drawing support mainly from a distinct segment of Indonesian society or a stream (aliran) of political thinking mostly focused around the issue of the role of religion and the state, usually with a particular regional strength. These were all formed—or reformed—during the blossoming of democracy in 1998–1999 and have historical antecedents in the New Order.

The largest is Megawati Soekarnoputri’s PDI-P, which leads the “nationalist” stream. Four parties largely compete for the “traditionalist” and “modernist” streams of Islamic thinking: PKB, PKS, PAN and PPP. Golkar sits less comfortably within this categorisation, but it has an electoral base originating from its origins as the official regime party during the Suharto era.

The other category of populist or “presidentialist” parties have been created since 1999 as personal political vehicles for leading politicians who, for legislative and campaigning reasons, needed to create a party to support their presidential bids or, failing that, secure individual oligarchs a powerbroking role. Presidentialist parties now in include former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s Partai Demokrat (PD), incoming president Prabowo Subianto’s Gerindra party, media tycoon Surya Paloh’s Nasdem party and, until its failure to enture the DPR in 2014, the Hanura party founded by retired general and failed Golkar presidential candidate Wiranto.

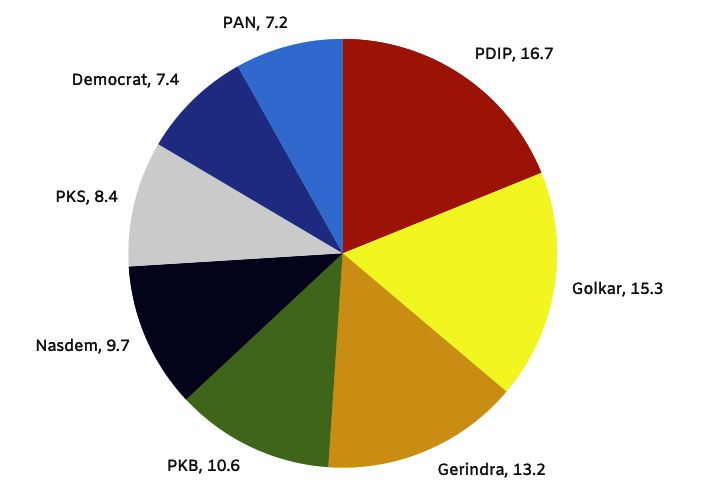

Vote share in 2024 DPR elections by party

Source: Indonesian General Elections Commission (KPU)

The first thing to note in the 2024 results is that Prabowo’s personal vehicle Gerindra, with 13.2% of the vote, has done relatively poorly given that its key public figure won a decisive victory in the presidential poll. The party did achieve a 0.7 percentage point increase over its 2019 result, but it still only won third place after PDI-P and Golkar.

Gerindra might have hoped to benefit from the “coat tail effect”, a longstanding trope in Indonesian political commentary suggesting that winning a presidential campaign brings success in the parliamentary elections. This was most spectacularly illustrated by PD which, after being minted for SBY in 2003, won 7.5% of the 2004 DPR vote and then swept the field with 21% in 2009 ahead of SBY’s landslide reelection that same year.

Gerindra’s solid but unspectacular result in 2024 suggests the party does not attract widespread voter support beyond those drawn to the profile of its leader. It raises questions about Gerindra’s base in any of Indonesia’s regional, religious or socio-economic communities which sustain the longevity of a number of other parties. The result this time could be seen as a repudiation of the power of the “coat tail effect” effect— although it will be interesting to see how Gerindra performs in the 2029 DPR election if, as seems likely, Prabowo stands again. Could it replicate PD’s experience and win handsomely from its association with a winning incumbent?

The biggest loser is PDI-P. Although it received the highest vote (16.7%), it lost 3.2 percentage points from its 2019 performance. The only time PDI-P has performed worse than this was in 2009, when it crashed to 14% percent as it was swept aside by PD in SBY’s reelection year. A major factor appears to be that many previous supporters were influenced by incumbent President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s break from PDI-P, putting his immense personal prestige behind Prabowo’s candidacy.

This result represents a huge blow to Megawati and her imperious style of leadership of PDI-P, although her iron grip of the party is unlikely to be weakened. Relations between Jokowi and Megawati were always distant at best, and she gave only half-hearted support to Jokowi’s first presidential bid in 2014. There were frequent tensions between the two, particularly over Megawati’s attempts to subordinate Jokowi into the status of a mere party functionary of PDI-P.

Thus, in the case of PDIP at least, it appears we may have witnessed a coat tail effect of a rather different kind, where a turncoat incumbent was able to shift some vote away from his own party, even if he didn’t take it to the party of the presidential candidate he supported.

The biggest winner is Golkar, which increased its vote by 3.1 percentage points over its 2019 result, going from 12.2% to 15.3%. This is the biggest boost experienced by any party in 2024, and has placed it in second place behind PDI-P. Although a good result, it is only slightly ahead of the party’s 2009 and 2014 results. As one of the parties supporting Prabowo’s presidential bid, Golkar may have partially benefitted from the swing away from PDI-P, although this does not fully account for its performance.

Explaining the Prabowo landslide

Prabowo’s win was made possible by his enduring strongman appeal and a playing field tipped in his favour by Jokowi.

PKB experienced a small boost of 0.9 percentage points. Its 10.6% of the vote makes it the fourth largest party in the DPR, not far behind Gerindra. This maintains the consolidation of the party’s support over the last three elections, recovering from its disastrous low point of only 5% percent in 2009, at a time when the party was riven with internal splits. Indeed, this year’s result is very close to what PKB received at its debut election in 1999.

Similarly, Nasdem attracted just under a 0.9 percent point gain, winning 9.7% of the vote. This party has a developed a modus operandum of sponsoring candidates from wealthy and influential families in the regions, using their local profile and resources to win seats in the party’s name. Nasdem has also been noted for putting forward women from such regional “dynasties”, resulting in a strong profile of female DPR members in the party’s ranks.

PKS achieved virtually the same result as in 2019. Its 8.4% of the vote is just above the average it has achieved in the four elections from 2004 to 2019, suggesting that the party has been unable to break out from the confines of its particular constituency and broaden its support amongst voters from different Islamic traditions or amongst more secular-minded Indonesians.

PD has registered a small decline, down 0.4 percentage points to 7.4%. From its glory days when SBY was president, the party has suffered a continual erosion of popularity in subsequent elections. SBY has repeated the tendency of Indonesian leaders to succumb to the temptations of dynasticism, appointing his politically inexperienced son, Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, as leader of the Democrats to the exclusion of better qualified veterans of the party.

PAN slightly improved on its 2019 election, receiving 7.2% of the vote, an outcome that is a little above its average result in all elections since 1999. While apparently maintaining a consistent support base, the party has again shown itself unable to break from its core constituency.

PPP narrowly missed crossing the 4% threshold that election laws set as the “parliamentary threshold” that allows a party to be assigned seats in the DPR. PPP won just 3.88% of the vote: in a crowded field of parties appealing to the various streams of the Islamic community, it appears PPP has struggled to maintain its raison d’être in the post-Suharto era.

What coat-tails? Prabowo speaks at a Gerindra party meeting in West Java, December 2023. (Photo: Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya on Facebook)

Dividing the spoils

The next big battle will be for control of the DPR and its committees. The current law regulating the legislature’s operation—known by its Indonesian acronym, the MD3 law—states that the powerful DPR speakership goes to the party with the highest representation, with the four deputy speaker positions being taken by the parties in the second to fifth places. The leadership to be sworn in in October 2024 will therefore look exactly the same as the outgoing parliament’s, with PDI-P in the speaker’s chair and Golkar, Gerindra, PKB and Nasdem holding the deputies’ gavels.

The leadership and deputy leaderships of the parliamentary committees are distributed amongst the parties in proportion to their number of seats. With some 90 positions available, the apportionment of these influential titles will see a game of labyrinthine politicking.

Because PDI-P holds first place with such a narrow lead, the newly-strengthened Golkar ranks may begin looking with envious eyes to the speaker’s position and attempt to change the MD3 law and have this strategic position decided based on a majority vote of the parties rather than assigned by right to the biggest party. Golkar’s capacity to change this or other legislation will, of course, depend on the balance of power and allegiance amongst all the parties. Thus the final big remaining question is which grouping of parties will control the majority in the DPR.

Prabowo will need to build a coalition of parties to support his administration in parliament. Under Indonesia’s presidential system, the president does not need a parliamentary majority, but a troublesome parliament would be a major impediment for his presidency. At first glance, this might seem a difficult task for Prabowo because Gerindra is far short of a majority and even the addition of all the parties that supported his presidential candidacy only brings his numbers to 43%.

As president Prabowo will undoubtedly follow the approach of his predecessors and entice as many parties as possible into his tent. Most parties will likely join his parliamentary alliance, with the possible exception being PDI-P. While PKS stayed out of Jokowi’s governing coalition, it may find Prabowo a more amenable president. In any case, PKS may conclude that it gained virtually nothing in electoral terms as an opposition party in the last parliament and that jumping on the president’s bandwagon may bring more benefits.

While it is a truism that a healthy legislature requires a healthy opposition, past experience has shown that most Indonesian parties are more attracted by a share of the spoils of executive government than by the prospect of keeping the government accountable and providing an alternative government. This is where the politicking for DPR positions and jockeying for cabinet posts are directly connected to each other: a party’s DPR numbers are its main bargaining chip for a place in cabinet and a ministerial post is the key inducement in the president’s hand when seeking party support.

So the upcoming weeks and months will see a continuing flurry of flirtations, backroom meetings and negotiations amongst Prabowo and the leaders of the parties to patch together a cabinet which roughly reflects the balance of forces in the DPR. Prabowo’s cabinet will, like its forerunners, be a combination of party figures and, especially in the economic portfolios, technocratic experts.

DPR Speaker Puan Maharani with her mother Megawati Soekarnoputri, June 2023 (Photo: Puan Maharani on Facebook)

A stabilised two-track party system?

The parliamentary election has produced few surprises and a lot of continuity. The first two or three elections after 1998 saw major shifts in voter support. Firstly, the 1999 and 2004 elections saw a rapid decline in the initially high vote going to PDI-P, Golkar and PPP as their networks decayed and the influence left over from the Suharto era waned.

Secondly, from 2004 to 2014 there was a fragmentation of the electorate as the “presidentialist” parties sprang up to drive the political ambitions of new leaders unwilling or unable to accommodate themselves in the existing party hierarchies. This contributed to a flattening out of the different levels of support for each of the parties, with the parties holding the most seats in the DPR not being very much bigger than the smaller ones.

Since 2014, however, the parliamentary scene has stabilised, or perhaps stagnated. The parties appear to have succeeded in holding on to a core constituency of supporters, but have not been able to make progress beyond their base. Most of the parties have achieved results that are very close to their average performance over the last three elections.

What is it that these parties offer to their respective constituencies and how do they keep their support? When repeated studies and surveys have indicated a low level of identification with (and loyalty to?) parties, this raises the question of how it is that the party spectrum appears to have settled down into a set number of players with an ongoing connection with a group of voters.

Amongst the overall scene of stability, there were three small notable developments. Firstly, although PPP was a victim of the legislative mechanism of the threshold, its 2024 results are only the last of a series of declines that speak to the critical importance of maintaining a clear voter base. Secondly, the virtual disappearance of Hanura shows the potential fate of presidentialist parties if their only appeal is the personality of their founder—hence the eagerness of SBY to keep his family in control of PD. Thirdly, the failure of the Partai Solidaritas Indonesia (PSI) to break into the circle of established parties is a striking illustration of the difficulty of shifting the voter attitudes without a constituency that is better defined than that of “youth”.

The fact that the most recent entrant to the parliamentary contest, Nasdem, has seen steady growth in the last three elections through attracting the support of local notables, while having a relatively low-key national leader, attests to efficacy of grounding a party in localised politics. And the experience of PKB’s recovery from its near-death experience in 2009 shows that any party claiming to speak for a particular sector of society must be credible amongst the grassroots of that constituency.

Given the attention that scholars have paid to the role the distribution of patronage and “money politics” plays in election campaigns, and the fact that the party vote has actually changed very little over the last three elections, we need to measure the extent to which moving large amounts of resources does actually materially affect election results. Is the distribution of largesse only as important as, say, the coat tail effect, or is it even less than this? It may be that spending money—and being seen to spend money—is important for a party’s credibility as a big player, and for servicing its own supporters, but that it cannot really move large masses of voters.

The presidential and parliamentary elections appear to have taken on a very distinct character during simultaneous polls. In these last two elections, the presidential campaign has become essentially a contest in the “air war” conducted at a national level and especially reliant on the mass media and, of course, on the personality of a handful of players. The DPR elections, on the other hand, while still affected by the colour and movement of the presidential competition, appear to be increasingly dominated by the tactics of the “ground war” where local affinities, local figures and local patronage have become critical to success.

Separate presidential and parliamentary elections have gradually given rise to a two-track electoral contest and an associated strengthening of a two-track party system. Simultaneous presidential and parliamentary elections seem to be giving further impetus to this trend. There is fertile ground here for further research.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss