Ahead of Malaysia’s 14th general election (GE14), Johor’s crown prince Tunku Ismail Ibrahim (popularly known as TMJ) issued a statement earlier this month essentially calling for the maintenance of the incumbent UMNO government. It was also a thinly veiled criticism of former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamed, who had curtailed the powers of the hereditary rulers during his 22 years in power, and who’s now leading the opposition coalition Pakatan Harapan (PH) as its prime minister-in-waiting. The royal houses rarely intervene so publicly in national political affairs, and the Johor royal family has made the headlines in recent years. Most cutting was the TMJ’s reminder to political leaders: “Do not question the sovereignty of Johor.”

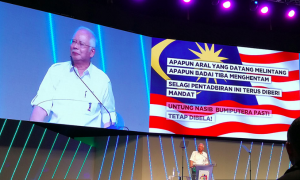

Despite government being in caretaker mode, both federal and state-level parties have been offering “goodies” to their voters in these final weeks before GE14’s polling day on 9th May. The federal Land Public Transport Commission (SPAD) made 67,000 free RM800 (A$269) fuel cards available to taxi drivers in Peninsular Malaysia, while in Selangor state, chief minister Azmin Ali handed out cash allocations, laptops and iPads in his constituency. In Penang, responding to Prime Minister Najib Razak’s promise to remove road tolls for motorcyclists at the two bridges linking island and mainland Penang, chief minister Lim Guan Eng said all tolls would be abolished if PH takes federal power. In Johor, chief minister Mohamed Khaled Nordin announced that three entertainment parks worth almost RM8 billion (A$2.7 billion) would be built in the near future.

In an environment so highly focused on national-level politics, what role do the states play? Are federal–state relations relevant, and do they impact electoral outcomes in any way, and how?

MALAYSIA IS A complex creature. While it was formed as a constitutional federation and has all the trappings of a formal federalism, in reality it practises only a weak or highly centralised form of federalism. Over the years, greater power and control have become increasingly concentrated in the hands of the federal government, starting with the abolishment of local council elections in 1965.

The federal government’s powers are far-reaching, and states have little say over their own state economies. Ever since the early 1970s, when then prime minister Tun Razak (Najib’s late father) initiated a policy of a kerajaan berparti or a government run on UMNO’s philosophy—at a time when the race-based affirmative action New Economic Policy (NEP) was being rolled out nationwide—states have been largely subservient to national-level ideology and direction. Up until 2008, UMNO and Barisan Nasional (BN) arguably considered states as natural extensions of the centre, operatives necessary to fulfill the national mandate of economic development—the more centralised, the more efficient.

Today, the Prime Minister’s Department budget alone is more than five times larger than the state budget of Selangor and almost nine times larger than Penang’s, according to the 2018 budget. Although policy areas such as local government and land are supposed to be under state jurisdiction, according to the federal constitution, there exist entities like the National Council for Local Government and National Land Council, both chaired by a federal minister, both with strong influence over how such matters are managed within the states. There are also numerous provisions in the federal constitution that permit the federal government to actively intervene in a state’s affairs. The Yang di-Pertuan Agong (King) can declare an emergency with the advice of the Prime Minister for the sake of maintaining “national security and public order”, which is extendable to any matter within the legislative authority of a state.

In the context of Malaysia’s single-party dominance, where UMNO-BN has never lost power, it’s no surprise that, with a few exceptions, BN-controlled states are not as autonomous since their decisions are largely governed from the centre. Federal infrastructure projects would invariably receive the required state developmental order approval, for instance (states have the power to withhold this).

On the converse, whenever opposition parties have taken over state governments, they have been punished. For instance, oil-rich Kelantan and Terengganu have had their oil royalties withheld whenever opposition party Pas won power. The federal government banned log exports from Sabah which resulted in that state’s income falling drastically when it was under opposition rule in 1991. Budget cuts and delays in development project approvals have also been standard practice. Some states have resorted to depending on natural resources for their funding, since that is one of the few areas states manage. Sometimes this results in tragic outcomes: for instance, Kelantan was accused of excessive logging, which many argue resulted in the tragic floods of December 2014. Even BN-controlled states like Pahang (Najib’s home state) have also had to rely on natural resources to boost state income, through both logging and bauxite mining.

WHEN PAKATAN RAKYAT took over control of the states of Selangor, Penang, Perak, Kedah and Kelantan in the wake of 2008’s now-historic 12th general elections, State Development Offices (SDOs) were physically removed from state premises, with funds directly channeled from the federal government and completely bypassing the new state governments. The federal government also set up Village Development and Safety Committees (JKKKP) that report directly to the Ministry of Rural and Regional Development. In the recent redrawing of election constituency boundaries, many individuals reportedly supporting the exercise and the new Selangor boundaries were in fact representatives of the JKKKP federal committees.

Malaysia’s richest states Selangor and Penang have had to contend with federal government interventions in multiple ways over the past decade, including federal instructions to civil servants that ran counter to the states’ agendas. Although civil servants are supposed to serve the government of the day, states’ senior civil servants (except in Johor) are appointed and promoted from the federal service and hence are put in the difficult position of serving two masters simultaneously.

For example, in 2010 when the Selangor state secretary was due to be replaced, the federal Public Service Commission announced the name of the new state secretary without the Selangor chief minister’s consultation. The chief minister called for a special state assembly sitting to amend the state constitution, which would give the chief minister and the Sultan of Selangor the power to choose senior state officials. But this proposed amendment did not get the required two-thirds majority in the state parliament, and the chief minister was forced to accept the federal government’s choice of a new state secretary against his will.

However, because these two states are highly industrialised and urbanised, they have had a different experience to previous opposition (non-BN) states, which were primarily rural in nature (Kelantan, Terengganu and Sabah). In the past, the BN federal government punished rural states by withholding funding and development, but it was no longer able to do the same in Selangor and Penang. These states have drawn from existing thriving industry, state-linked companies, and land development for their resources. Because these states also contribute disproportionately to the national economy, it was also foolhardy to threaten the economies of these states.

Over the past decade, both Selangor and Penang have sought to promote themselves as better-run states, demonstrating better budget outcomes and economic management, people-friendly services and policy delivery, and the ability to maintain investments and a strong economy. Such messages have been used by both states to position themselves as an alternative federal government model. In fact, some state policies have been imitated at federal level: Selangor’s Rumah Mampu Milik low-cost housing programme arguably inspired the federal-level PR1MA programme.

Selangor used its legislative assembly’s Select Committee on Competency, Accountability and Transparency (SELCAT) to investigate corruption cases under the previous chief minister Khir Toyo of UMNO-BN. Selangor’s UMNO has not been able to recover from these negative perceptions, and lacking a strong leader, the state opposition has been weak. Previous state patronage systems have also been redirected, resulting in curtailed revenue streams that would have previously accrued back to central UMNO headquarters. Both Selangor and Penang state governments introduced Freedom of Information Enactments and implemented asset declaration systems for their Exco (state ministry) members. These two measures are unprecedented, and have not been replicated by other state governments nor the federal government.

THERE WERE MANY occasions in which overlapping jurisdictions caused confusion in opposition-held states. The Selangor government bore the brunt of dissatisfaction over several water shortage incidents in the state over the past decade. ‘Water supplies and services’ was transferred from the Federal Constitution’s state list to the concurrent list in 2005, where both federal and state government have joint control over how water is treated and distributed in states. The restructuring has been a long drawn out process because of disagreements between the federal and state governments, made more complicated because there were four separate concessionaires to negotiate with. But voters care little for the details, and demand the issue be resolved quickly.

Such federal–state political competition has allowed other states to embolden themselves. For instance, the states of Sarawak and Sabah have become increasingly vocal in their demands for greater autonomy and to restore the terms of the Malaysia Agreement of 1963. The Sarawak state assembly passed a motion to demand a 20% royalty, instead of the 5% that the state currently receives in petroleum revenue sharing agreements with the federal government, Petronas and international oil companies. Sabah opposition politicians followed suit to demand the same. Negotiating with Putrajaya has resulted in Sarawak being able to set up its own oil and gas company, Petroleum Sarawak Berhad (PETROS), which is to work with Petronas and become an active player in the oil and gas industry by 2020. BN-led Johor has also fluffed its feathers, where crown prince Tunku Ismail Ibrahim declared in 2015 that the state had a right to secede from Malaysia if the terms of the federal agreement are violated, and the term “Bangsa Johor” (the Johor race) has been used repeatedly to mark out a specific state identity, separate from the rest of the nation’s.

Having an opposition coalition leading at the state level offers voters a glimpse into how it will govern at the national level. The picture isn’t always rosy, where there have been complications, in part due to the intra-coalition conflicts on religion and race. More so in Selangor than in the more ethnically homogeneous states of Penang, Kelantan and Kedah. Selangor has had to deal with sensitive issues such as alcohol, entertainment centres, the relocation of a Hindu temple, and the confiscation of Malay Bibles. In so doing, the state government has had to find a delicate balance where all parties—of various inclinations—will agree to compromise. Although the Islamist party Pas is no longer part of this coalition, its representatives were in the Selangor Exco right up to the recent dissolution of the state assembly. Selangor Pas was less vehement in its criticisms of other coalition partners like the DAP, compared to their national counterparts. Hence the state Pakatan Rakyat coalition outlasted its national coalition (which has regrouped with different partners as Pakatan Harapan), presumably because it wanted to enjoy the benefits that state power provides. Perhaps this predicts a future in which state and national coalitions need not be formed with the same parties?

There have also been allegations of continued patronage within the states of Selangor and Penang, through well-oiled deals with private developers and contracts at local councils, demonstrating that opposition-led states are unable to break out of the BN model of patronage politics. But unless political party financing is reformed, all parties will depend on such patronage systems for survival. Politicians in Malaysia are expected to provide their constituents with money—gifts for funerals, weddings, mosques, associations and so on. And being in opposition is no exception. In fact, the political culture of clientelism is so deeply rooted that the constituents expect it of their elected representatives.

From the streets to the courtroom: judicial electoral contestation

Bersih’s legal strategy to check on electoral integrity has exposed and revealed much about the redelineation process, testing the relationships between Malaysia’s political institutions.

In some—but not all—cases, the successes of Selangor and Penang have been used as a narrative to convince voters of the economic possibilities these states can achieve in opposition PH hands. Whether such successes can be replicated is dependent on the nature of the state, and only Johor is similar to Selangor in urban and demographic makeup. Other states the opposition hopes to win over like Kedah are more rural. There are other indications that voters in Kelantan are likely to support BN over Pas, given the latter has been unable to contribute meaningful economic development to the state—thanks primarily to issues described above where rural opposition states are cut off from federal resources.

Healthy political competition between the federal and state governments has expanded policy possibilities, as both levels observe, challenge, adapt, learn from, and imitate the other. Whatever the outcome, it’s clear that states—especially those led by the opposition—are becoming increasingly conscious of their distinctive state identities. Some have expressed their desires for greater autonomy and independence, and are challenging what was previously considered a de facto centralised federal government. This new federal–state dynamic is something any ruling federal government will have to get used to.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss