It’s quite a dull Ministry actually, says Dr Xavier Jayakumar. “There’s a bit of apathy on the part of people to understand my Ministry … because I deal with water and forest and mineral resources and land. Only the people who are involved in [related] industries and conservation are interested”.

To highlight the importance of natural resource management, the Minister of the Malaysian Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources is grabbing attention with a roar. He has secured the backing of the army and police to help his overstretched wildlife rangers save the iconic Malayan tiger (Panthera tigris jacksoni) from extinction. Only firepower can tackle the key threat: poachers feeding into international crime syndicates. Fewer than 200 tigers are left in the wild in Peninsular Malaysia (tigers are not found in the Bornean states).

From a conservation standpoint, this level of attention is a seminal first for Malaysia’s new government. Promisingly, it is indicative of the broader leadership, engagement and reform being undertaken to ensure environmental issues are being tackled, even if there are problems in planning, execution and communication. Launched in March, less than a year since Pakatan Harapan took over, the tiger conservation programme addresses the aforementioned general apathy, by drawing attention to the fate of a charismatic predator that is a national symbol. Employing military tactics in the name of protection elevates the status of wildlife and other natural resources in the public imagination, an imagination in which conservation plays second fiddle to economic and developmental progress.

The “Save The Malayan Tiger” programme employs firepower to tackle poaching (Photo: harimau.my, KATS/Perhilitan)

In addition, the programme is comprehensive, including safeguarding tiger prey populations, addressing demand for tiger parts, and uniting stakeholders, from federal agencies, state governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to local communities and the general public. Crucially, it goes hand-in-hand with harsher laws and a separate large-scale reforestation programme that incorporates tiger habitats.

In reality, the Ministry does not even have enough funds to cover the RM44 million two-year programme—there is a shortfall of RM20 million—but the Minister has proceeded with it anyway, confident funds can be raised along the way. “Enough is enough, this has to stop”, says Dr Xavier.

Seeing this programme in action has the conservation community cautiously optimistic that federal government leadership will finally see the proper execution of two plans on which this programme is based: the National Tiger Conservation Action Plan for Malaysia for 2008–2020 and the 2009 Central Forest Spine (CFS) Master Plan for Ecological Linkages.

The former’s goal is to double tiger numbers from 490 to 1,000; instead, the numbers have plunged by over 60%. The latter’s goal is to redress forest fragmentation in the Central Forest Spine, referred to as the peninsula’s “most important ‘green heart’ … of critical habitats”, including for tigers. Instead, according to forestry watchdog Hutanwatch, project execution had been faltering. Between 2010 and 2016, remote sensing analysis showed the project area actually lost 60,000 hectares of forest within linkages that were meant to be restored.

In both cases, non-profits and research groups had been doing the heavy lifting and lobbying.

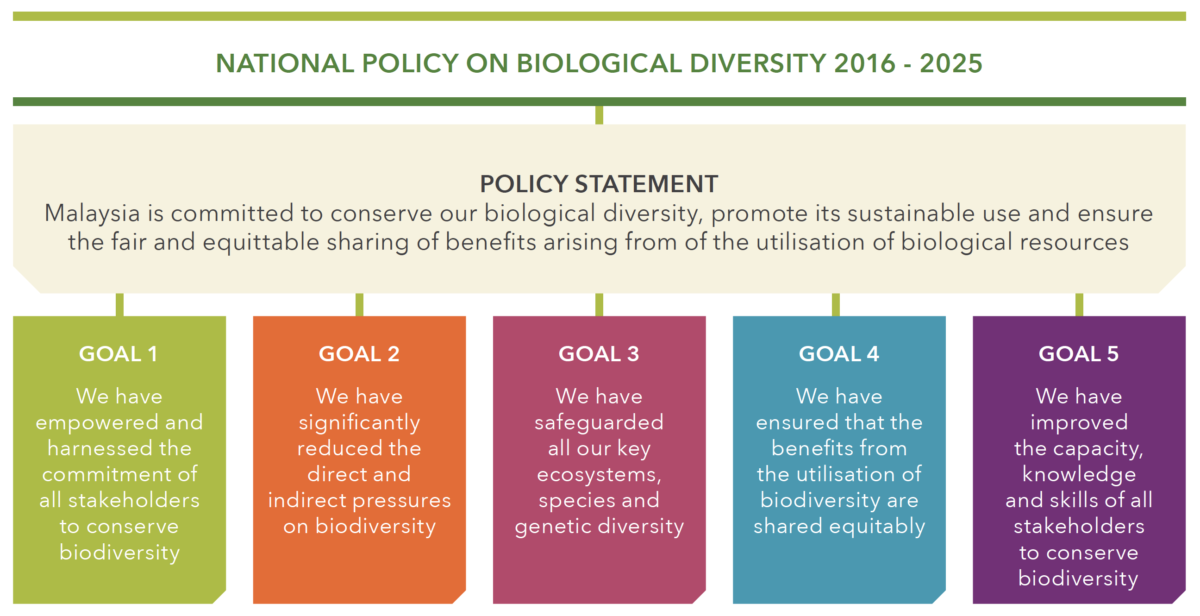

Now, hope has also been raised for the implementation of the National Policy on Biological Diversity, which has seen scant movement a fifth of the way through its 2016–2025 timeline. The Ministry affirms this as “the guiding document for all biodiversity planning and management at the federal and state level”. The policy also forms part of Malaysia’s response to international conservation convention obligations.

The guiding document for federal and state biodiversity planning and management. (Photo: National Policy on Biological Diversity 2016-2025)

To implement the policy, the highest ministerial decision-making and coordinating policy implementation bodies set up by the previous regime are being retained while stakeholder and federal-state consultative platforms the policy calls for are finally being put together. The policy is also being reviewed.

So while it appears that some things are finally getting done, conservation groups are urging more comprehensive reform of the relevant legislation and institutions.

A priority should be the 35-year-old National Forestry Act, says Surin Suksuwan, environmental consultant and a member of the World Commission on Protected Areas. The Act governs the peninsular states while Sabah and Sarawak have their own enactments. “Why isn’t forestry put under scrutiny in the same way as wildlife, even by NGOs and the public? The Forestry Act has been ‘under revision’ for too many years; likewise, the National Forestry Policy 1978, which was last revised 14 years ago”.

Between 1992 and 2014, Ministry figures show a loss of 216,000 hectares of forest cover in Peninsular Malaysia. These losses have further fragmented forest complexes, exacerbating biodiversity decline.

“Forestry laws are still very much orientated towards exploitation rather than emphasising protection”, says Suksuwan, adding that the forestry policy should set the tone for the Act. These emphases would be on protecting wildlife habitats and other forest functions such as ecosystem services. Ecosystem services are benefits that humans gain from the natural environment and properly-functioning ecosystems, for example, water for drinking from forested water catchments. “It should also include a strong component of public participation”.

What is heartening is that the new government has specifically listed reviews of both the Act and Policy in its Mid-term Review of the 11th Malaysian Plan 2016–2020. Minister Dr Xavier is looking at getting the Bill for the Act tabled in Parliament, at the latest by early next year, after stakeholder consultation.

Unlike conservation groups, however, he is also looking at the amended Act’s strengthening not just forest conservation but also the sustainable forest-industry component. He clarifies, “Deforestation and reforestation go hand-in-hand. At present, we have 55.3% of forest cover throughout the country, so we want to keep that number intact…

But to keep that number intact, we also need to find new avenues by which industry can move forward because the demand for tropical wood is huge outside [Malaysia]. Because of that, we are going into reforestation in the form of [forest] plantations and [will] develop an economy out of it”.

Malaysia will maintain at least 50% of its area as forested. (Photo: Author)

He explains that these new initiatives are federal projects with foreign direct investment from companies “interested in putting in the money to get the system going”. Last year, exports of timber and timber-based exports earned the country an estimated RM23 billion.

Care will need to be taken to ensure these forest plantations do not lead to more deforestation, warn conservationists. While EU-led campaigns blame tropical deforestation on oil-palm plantation expansion, environmental NGO Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM) says that in the last 15 years, “the total size of forested areas targeted for pulp and paper and timber tree plantations may in fact surpass that for oil palm”.

Still, Dr Xavier emphasises the government’s commitment to maintain a minimum 50% of the country as forest, a commitment that was made at the 1992 Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit by Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad during his previous stint in office. This call has been echoed by several current Ministers.

One is the Minister of Primary Industries, who is struggling to battle the impact on trade of international campaigns linking palm oil and deforestation. She has banned the conversion of government forest reserves into oil palm plantations nationwide and, in fact, announced a 2023 cap on the crop’s total cultivation area. The cultivated area is already at 89% of that cap.

Maintaining that minimum 50% forest equation is also the carbon-sink strategy of the Minister of Energy, Science, Technology, Environment and Climate Change. To fund the no-deforestation commitment in order to mitigate climate change, she is seeking international results-based financing through REDD Plus (the UN Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation).

On the ground, stopping deforestation and implementing reforestation programmes means working with states and the tricky maxim of Malaysian federalism, that “land is a state matter”.

Suksuwan explains the federal government’s limited purview: “Whenever a forest reserve in a state is excised, it becomes state land to be used for housing or plantations or mining. It doesn’t require any consultation at all. All it requires is for the member of the state executive council member in charge of forestry, to sign away that area. It’s as simple as that”.

Film review: ‘Asimetris’

A provocative documentary examines the asymmetries of Indonesia’s oil palm boom, but leaves some difficult questions unaddressed.

“The previous federal government demonstrated commitment to environmental protection by signing various international conventions. But when it is time for the states to implement what is pledged, the funds are not available. On the one hand, states lack capacity to manage [natural] resources. On the other, the resources provided by the federal government are far from adequate”.

He lauds the Pakatan government’s 2018 budget allocation of RM60 million for state governments to “protect and expand our existing natural reserves”. While the allocation is small and its disbursement mechanics have yet to be worked out, “this is probably the first time the federal government has framed funding this way, to help state governments, and because this is not specific, will allow states to come up with their own proposals”.

Dr Xavier is cognisant of these issues, having engaged with state governments, including those of opposition states. “When we tell them there’s to be no more deforestation … they quickly tell us we have to compensate them. So we are finding other means where these state governments can get income”.

He is starting with states that are “critical” in terms of having few alternatives to logging income, such as Kedah, Pahang and Kelantan. “We are looking at how we can approach it in a different way in order to make sure they leave the forest alone but … [adopt] new ideas … to get income. I think it will work if I show them how it is going to be done”. He declines to elaborate as discussions are still underway.

At the same time, Dr Xavier is taking a tougher stance. Regarding conservationists’ long-held concerns about weak enforcement and corruption in related agencies, he says, “I’m treating it as a national security issue, as far as the degradation of forest or deforestation is concerned. Because if we don’t get to sell this main commodity of the country [timber], we are going to be in deep trouble.

“The states have to come on board with us and work with us to make sure there is a proper balance and we get the right messaging out in order to protect [the] national interest. The states have to play a big role in this because the power is completely in their hands as far as land is concerned, also the policing and action that needs to be taken in terms of safeguarding these areas”.

He says the federal government is giving states time to “do things correctly” but warns that “if they go ahead and do things that will be detrimental to national security, then we have to do things differently”.

This new approach is in line with Pakatan’s larger reform agenda. Dr Xavier says that all federal ministries are undergoing reform. Most of the 18 agencies under him, for instance, are in the process of “renewing and changing or interpreting the laws that are currently in place”. As with the forestry and wildlife bills, he is hopeful of tabling these other new or amended laws by early 2020.

Recognising this window for change, SAM is urging the government to go further. “The Federal Constitution should be amended “to ensure that all Malaysians have the right to a safe and healthy environment as a fundamental right”, says Theiva Lingam, SAM’s legal advisor. “Many countries in South and Southeast Asia like Indonesia, Pakistan and the Philippines have done so”.

Malaysia should be aiming for environmental justice, she adds, ensuring socio-economic equity and ecological sustainability in natural resource management. For example, “senior Pakatan policymakers continue to show ignorance on the law when it comes to the indigenous customary land rights”, she says. “Some even appear to lack the understanding that the law does not only comprise statutory law, but it also includes common law, customs and usage having the force of law and judicial decisions”.

In fact, the judiciary and the Malaysian Bar Council have been quietly working towards environmental justice. When the new government came into power, the Bar Council’s Environment and Climate Change Committee submitted a reform proposal to them for the development of a policy on environmental justice.

An environmental justice framework would recognise people with rights and relationships with the wider ecosystem. (Photo: SKChong/SasyazHoldings)

“The policy’s intended to inform judges in decision-making”, says the committee’s co-chair, Kiu Jia Yaw. “It would be along the lines of enabling and protecting environmental justice and would be the basis for devising rules of procedure for environmental proceedings”.

The judiciary has already put up for discussion these very rules of procedure, and the Bar Council committee is working with them on this.

Kiu described this rule-change as an innovating and widening of the legal funnel to allow more civil litigants to seek judicial remedy. “Our laws are filtering out people who do not fit in that funnel, particularly people who are not land owners—a colonial legacy that our legal system continues to maintain—even though they have every right to a clean and healthy environment.

“We need to break out of our mental structures of land titles with their imagined boundaries and owners with their property rights … In pursuing environmental justice, we need to recognise these ecosystems for what they are and the dynamic relationships different human beings have with them”.

These environmental proceedings rules would enable private citizens, community groups, NGOs and even corporations to bring cases of environmental harm to court to be heard.

“This would open up a different level of engagement”, he adds. “It is a profound thing when you give power to people. Then there is no longer the excuse of saying, ‘why should we care so much about the forest or the river’, because hey, now you can do something about it! That’s empowering. It changes mindsets. And it’s an important part of democratic participation when these narratives can come to court”.

While the teams have a long way to go due to the complexity of the task and the need also to engage with stakeholders, Kiu is more optimistic about these rules’ seeing the light of day under the new Pakatan government.

However, reforms related to conservation will only be effective if instituted together with larger overall reforms. The bruising experience of the previous Najib era shows that separation of powers in democracy is crucial to ensuring that no one branch—legislative, executive or judicial—controls and can therefore destroy the whole system.

Says Dr Xavier, “The separation of the executive and Parliament is taking place. But this is also a learning process for the new government because it was not there before. Now we are introducing new ideas whereby we will see more democratic processes and more transparency and check-and-balances between the executive and Parliament”.

The senior Pakatan minister, who is heavily involved in this reform process, added that “this will take a bit of time because it’s a transitional period … We are looking at all models, but we have to tread carefully because we are in an experimental stage, trying to see whether these changes are appropriate for the country”.

Where conservation is concerned, it is still too early to gauge if the new government can achieve lasting change, but the steps they are taking are positive. Using a multi-agency and holistic approach to safeguard biodiversity, working out solutions to incentivise states to keep their forests, and effecting legal and institutional reforms all pave the way towards environmental justice and, ultimately, sustainable development.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss