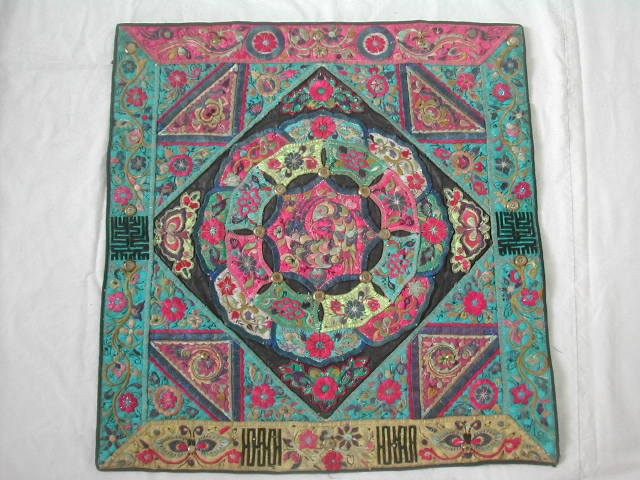

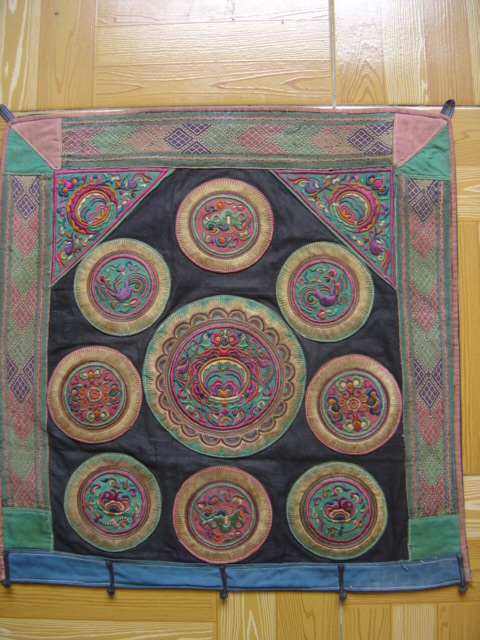

The highland, minority cultures of southern China and southeast Asia have sustained a rural, agrarian, and traditional way of life for centuries. Groups such as the Miao (Meo), Hmong (Mong), and Dong are well-known for their highly developed sewing skills. Their clothing is frequently embellished with intricate stitching and imaginative designs. In the absence of a written language, motifs — such as the butterfly, the chrysanthemum flower, the dragon, and the spiral — that evolved over generations are employed for their symbolic meanings.

Older lady with Miao babycarrier in Shidong. Photo: Andre and Agnes VERBURGH-MUYLLE/Ostend (Belgium).

Among the most visually expressive articles of embroidered clothing are the baby carriers, and there are two good reasons for this. One is that they serve to advertise – to potential partners in marriage – the skill, imagination, and perseverance of the young women who create them. The second is that they are replete with symbols and imagery that are deemed important to the well-being and future fortunes of the children who will ride in them.

And so, the baby carriers are not merely decorated utilitarian objects, they are also integral to the continuance of the cultures that create them.

These traditional cultures are undergoing rapid change, especially in China, where rural-to-urban migration is the de facto government policy. One consequence of this change is that, within the minority groups, the sewing arts are becoming much less frequently passed along to the next generation. While baby carriers continue to exist, the time-consuming, finely-crafted ones with a traditional sensibility are becoming ever harder to find. They are becoming a lost art.

Knowing nothing about this situation, I began collecting vintage Miao and Dong baby carriers a few years ago for purely aesthetic reasons. Enamored with their beauty and creativity, and enchanted by their exoticness, I sought out as many good examples as I could find.

Two and a half years later, my collection stood at 5,000 pieces, and I was exhausted. The great majority of those in the collection were probably made in the period between 1935 and 1975. It is hard to tell exactly how old a particular baby carrier is, but there are clues if one has a little knowledge. Some of the baby carriers exhibit their age in the form of surface wear, fading, yellowing, etc. Most textile experts can tell a hand stitch from a machine stitch, and the older pieces are comprised of mostly hand stitching. Other clues are the presence of aniline dyes, Chinese characters (a few of which relate to the Great Cultural Revolution), and stylistic markers (e.g. in one type of baby carrier, the older pieces have an orange background, whereas the more recent versions utilize a deep shade of yellow).

Comprised of about 15 dominant styles and 35 less numerous types, my collection is by no means comprehensive. Within Guizhou Province, for example, stylistic variations can appear from village to village. Even within a particular style, there are sometimes design elements that come from multiple sources.

For example, when a Miao group and a Dong group live side-by-side, a cross-fertilization of motifs can occur, resulting in a hybrid that seems as much Miao as Dong. Indeed, without good collection data, it can be tricky to know the exact provenance of many baby carriers.

As the title of this piece suggests, the collection is available (at no cost) for research and exhibition. Although I believe it is first and foremost an assemblage of beautiful embroideries, it is also a rich ethnographic trove. Among those who might find it a beneficial resource are authors, scholars, and students with an interest in art history, cultural anthropology, Asian studies, museum studies, aesthetics, design, or textiles. The baby carriers are organized and stored in a large workspace in Long Beach, California, USA. There is a website with more information and photographs at www.miaobabycarriers.com. Please feel free to contact me with any questions or comments at [email protected].

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss