Could controversial projects like the Myitsone dam be back on under NLD rule?

China — memorably described by Ryan Manuel as a dour brylcreemed uncle warning Myanmar of the perils of change and hope — has managed to rise from the armchair by the Christmas tree and offer tepid congratulations, with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi undertaking a less than riveting “exclusive interview” with Xinhua, China’s official press agency.

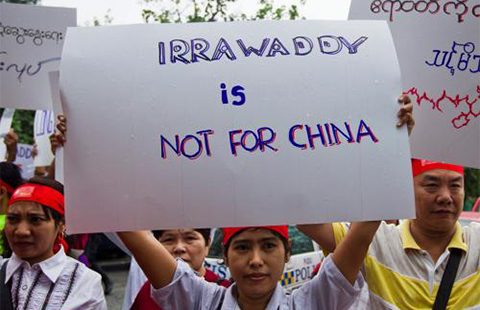

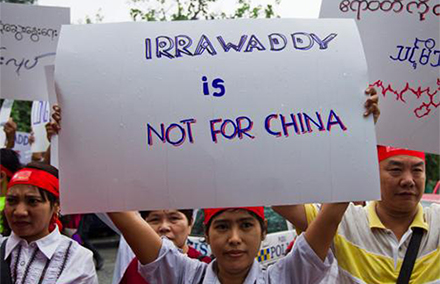

Many of China’s largest projects in Myanmar have arisen from partnerships with the military and officials of the now-routed former regime. Coupled with Suu Kyi’s openly admitted preference for Western resource companies such as Total and Chevron and her open letter of opposition which contributed to the suspension of the Myitsone Dam project, the election results do not improve the chances for our uncle and his megaprojects, even if China is still Myanmar’s largest trading partner by a large margin.

Add to this the personal doubts of Chinese leaders, expressed by academic Lin Xixing to The New York Times.

China does not like her, and there are reasons. Her father helped the Japanese fight the Chinese military in World War II. She has been close to the West, grew up in India and married a foreigner in Europe.

Yet some of China’s megaprojects in Myanmar will be harbouring hopes for a sunnier future under NLD rule.

The Letpadaung copper mine in Sagaing, a joint venture formed by Chinese firm Wanbao and a firm backed by the Burmese military, has displaced thousands of residents and was the site of mass protests in 2012 which brought the mine to a standstill. On the surface, the NLD landslide, driven by strong backing from civil society, should not bode well for the future of this project.

Yet the managers will be assured that then newly elected Suu Kyi was appointed as head of a commission and managed to find a solution to the impasse. Her commission backed the project, unsettling many activists, although the terms of the contract were rewritten to allow for greater localisation of the workforce and more revenues to flow to Napyitaw’s coffers.

The Chinese managers of the suspended Myitsone Dam project hold even greater hopes.

Against a background of popular protests, the dam was halted in 2011 for the duration of Thein Sein’s term, meaning that the project is up for renegotiation. Certainly, the company behind the project, Yunnan-based China Power International (CPI) and its local partners in the Asia World conglomerate will be encouraged by Suu Kyi’s reluctance to declare her opposition to the project during the election campaign, disappointing local activists.

In late 2013, I visited the Chinese border town of Houqiao, through which much of the materiel to support the Myitsone project flowed. Locals confirmed that hotels were now lying empty and auto repair shops were closing down one-by-one.

The border post 11 kilometres further up the road at Guyong was sleepy; its freshly built neo-Stalinist walls echoed in the afternoon heat. Yet the company’s website, and a string of laudatory press reports, give the impression that CPI has not given up on its Burmese dream.

On 18 November 2015, they posted a summary of their achievements in supporting the local community in Myitsone, tacitly admitting mistakes that they had made in the past. Previous experience suggests that it will be taken up word-for-word by Chinese media sources.

They detail efforts to support the livelihoods of residents in the resettlement villages, providing 1,210 tonnes of rice, repairing flood-affected houses and infrastructure, setting up a chopsticks factory in collaboration with the Kachin state government, and providing free electricity to allow the locals to experience the benefits of electricity, including “cooking, entertainment, hairdressing, commerce and culture. This small power supply will allow the villages to bustle with life.”

Scholarships to support children from the resettlement villages attend university (apparently funded by donations from company staff) are detailed, as are efforts to build churches and temples, and to establish close ties with influential local monks. While even pictures from CPI’s own website convey the depressing atmosphere of the resettlement villages, this investment is testament to the company’s hope that the project will be restarted by the new government.

Election results in Rakhine state, one area where the NLD did not sweep to power (although they will still likely appoint the chief minister) are a concern for some Chinese megaprojects. The (recently halted) Kyaukpyu-Kunming rail link, the Kyaukpyu special economic zone, and the Maday Island deep-sea port, all made a list of projects opposed by local Rakhine groups on the grounds of insufficient public consultation. Overall, though, the routing of many ethnic minority parties should make life easier for the boosters of China’s megaprojects.

China’s central government and Yunnan province are often at odds over their relationship with Myanmar, with the military and strategic concerns of Beijing clashing with the economic interests of Kunming.

Yet with the “one belt one road” initiative — reminiscent of Jiang Zemin’s Develop the West campaign that Yunnan was an enthusiastic participant in — rising on Beijing’s agenda, the two levels may now be on unity ticket to keep Myanmar open for business.

Dr Graeme Smith is a research fellow in the Australian National University’s Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs.

This article forms part of New Mandala’s ‘Myanmar and the vote‘ series.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss