Southeast Asia’s growing economic linkages with China generate political opportunities and strategic concerns in equal measure. Recent discussions have tended to focus on infrastructure projects, especially those associated with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, to gauge their significance and impacts, such projects must be understood against the broader context of Chinese investments in Southeast Asia.

Our SEARBO Policy Briefing provides an overview of the findings from our larger project collating and analysing region-wide, multi-sectoral data on large Chinese investments in Southeast Asian economies from 2005 to 2019. We identify regional trends, analyse the distribution of Chinese investments across Southeast Asia, and evaluate their key political and strategic significance.

Click on the cover image below to download the full policy brief.

Region-wide trends

Foreign investments in Southeast Asia originating from China grew twentyfold during 2005-19. Chinese investments expanded rapidly after the global financial crisis, when temporary declines in other sources of foreign direct investment (FDI) coincided with Beijing’s “going out” strategy encouraging international investment by domestic enterprises. Between 2013 and 2017, the BRI further enabled very large (at least US$1 billion) outward investments from Chinese enterprises. Moreover, China has diversified its investments across all the key industrial sectors and all the host countries in Southeast Asia.

Even so, for Southeast Asia as a whole, China is not yet a dominant investor. Between 2005 and 2018, China featured in the top three (non-ASEAN) foreign investors list only twice (in 2012 and 2018, both times in third place). In each instance, China’s share of the region’s total annual foreign direct investment (FDI) was only half that of the second largest investor, Japan. The EU, Japan, and the United States remained the three largest sources of FDI for Southeast Asia across this period.

Distribution of Chinese investments

Using the volume-based distribution of Chinese investments, we identify three groupings of Southeast Asian economies.

- Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore: These three key maritime economies were the top three destinations, together accounting for 57% of total Chinese investments in the region.

Indonesia is the top Southeast Asian destination for Chinese investments, which more than quadrupled to US$8.5 billion in 2015. The infrastructure sector (including the $2.4 billion Jakarta-Bandung Highspeed Railway) attracted a fifth of total Chinese investments in Indonesia, but the energy sector accounted for the bulk (around 55%).

Malaysia ranks as the second largest recipient, but Chinese investments rested on a few very major investments, such as the 2015 US$5.96 billion acquisition of all 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) energy assets, and the 2016 US$8.6 billion investments in the East Coast Rail Link and the Melaka Gateway Port.

Singapore is the third largest recipient of Chinese investments in the region. Reflecting the city-state’s economic profile, these were marked by major Chinese acquisitions of strategic service providers in energy, e-commerce, and logistics.

- Laos and Vietnam: These two mainland Southeast Asian neighbours each attracted around 11%, together accounting for just over a fifth of all Chinese investments in Southeast Asia.

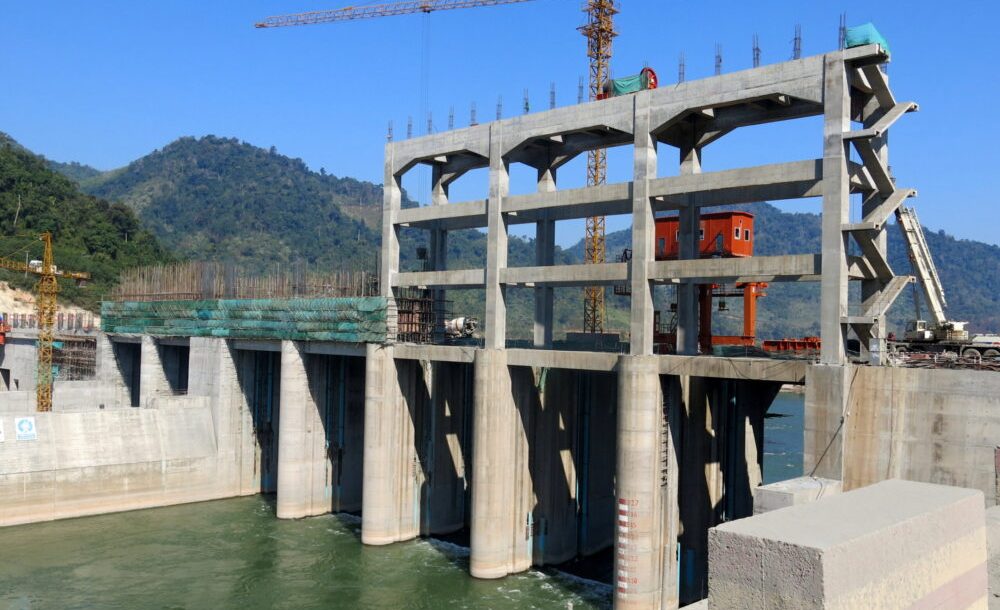

Chinese investments are concentrated in the energy sector – mainly hydropower in Laos, and coal in Vietnam. Laos also received sizeable Chinese infrastructure investment in 2016-18 for the railway connecting Kunming and Vientiane. Both Vietnam and Laos saw larger than regional average proportions of very large (over US$1 billion) Chinese projects.

Laos experienced a sharp increase in Chinese investments between 2013 and 2017, coinciding in part with BRI, but Chinese investment in Vietnam has been on a declining trajectory since 2010 because of their conflicting territorial claims in the South China Sea.

- Cambodia, Philippines, Thailand, Myanmar, and Brunei: Each country received 6% or less, together accounting for 21% of total Chinese investments in Southeast Asia.

Cambodia and Myanmar stand out for the high significance of Chinese investment in their economies, despite the smaller amounts involved relative to the two groups above. Cambodia has largely logged China as its top non-ASEAN FDI source in 2005-18. Unlike Laos, however, Cambodia attracts a wider range of FDI and thus is less reliant on Chinese investment. Myanmar’s reliance on Chinese FDI correlated with periods of international isolation under military rule.

In contrast, the Philippines, Thailand and Brunei attract small proportions of Chinese investment for various reasons such as reliance on other sources of FDI, nationalist sentiment, and the countries’ specific economic profiles.

Political and strategic significance

The largest volumes and shares of Chinese investments go to the most diversified and advanced Southeast Asian economies, but in some of the smaller developing economies, even small absolute amounts of investment can bring China top investor status. Countries that are less attractive to other major international investors are also likely to be more dependent on Chinese investment.

Concerns about over-dependence arise when one external source of investment is disproportionately important for a national economy. China has become the most important source of FDI for two Southeast Asian countries, Cambodia and Laos. Laos’ relative dependence on Chinese sources is higher, reaching a peak of 79% compared to a peak of 32% in Cambodia. China is consistently among the top three sources of FDI for only two other Southeast Asian economies: Myanmar and Singapore, but for very different reasons. Laos, Myanmar and—to a lesser extent—Cambodia are most likely to be over-exposed and potentially dependent on Chinese investments.

In general, sovereignty concerns arise over foreign ownership of critical national assets, and foreign control of service provision in critical sectors. In Southeast Asia, Chinese investments in two areas of critical national infrastructure stand out. Chinese companies are very significant in electricity generation and transmission in Singapore, the Philippines, and Laos. Chinese investment has also grown in the rapidly expanding and highly profitable telecommunications sector, including mobile and internet networks and providers in Thailand and the Philippines.

Vulnerability could also arise from very large Chinese investments in regional sectors which are strategically important for China, especially in Beijing’s quest for greater energy security. These range from Chinese acquisitions of Singapore companies for oil refining and international trading, to stakes in the refinery and petrochemical industry in oil-rich Brunei, to very large investments in Myanmar’s west coast to build oil refineries, ports to handle oil imports from the Middle East, and overland pipelines into China.

Myanmar now hosts critical Chinese infrastructure within its territory, and with its contiguous location, becomes integrated into Chinese strategic arenas and interests. China’s concrete stakes in Myanmar’s domestic politics have grown to include the management of ethnic insurgencies both on their shared border in eastern Myanmar and in Rakhine state in the west where such infrastructure is being built. Other strategically located port and transport infrastructure projects in the region have been slow to take off.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss