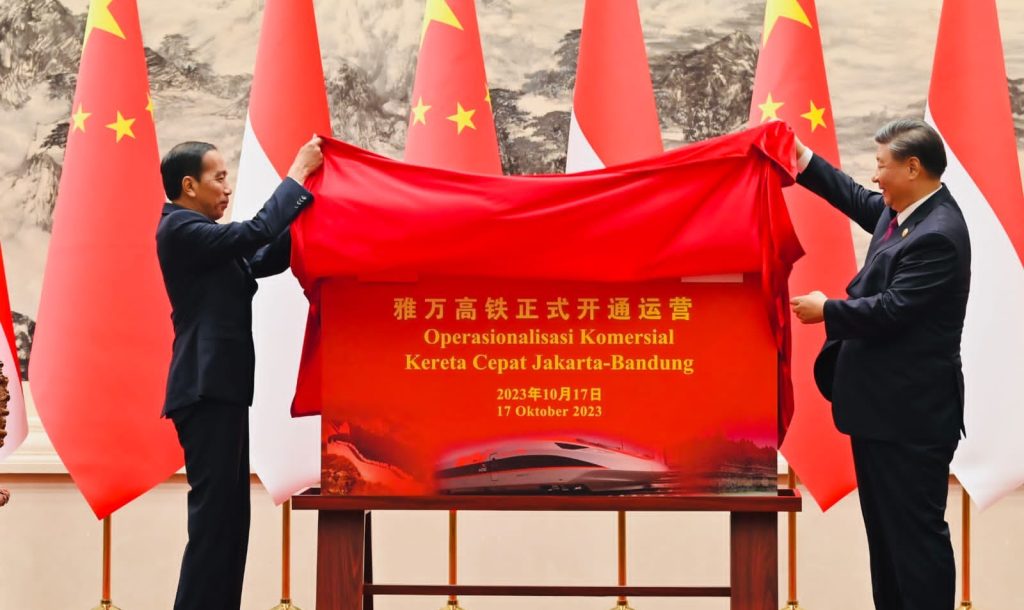

The Indonesia–China relationship has attained new dimensions over the past few years. The recent opening of the Jakarta–Bandung high speed rail (HSR)—a joint venture between Chinese and Indonesian state-owned enterprises—marks a significant milestone in bilateral relations.

The big-ticket project has overcome dissent to be embraced as an item of national pride. Indonesian government bodies are no longer shy about showing their closeness to Chinese counterparts, as political sensitivities become a thing of the past. State elites’ social media campaigns have recast Chinese capital as an important element in Indonesia’s highly-celebrated development plans—from investments in electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing and digital technology, the extension of the HSR route from Bandung to Surabaya and investments in the energy transition, to the controversial Rempang eco-city development.

Some observers, including Dewi Fortuna Anwar, have interpreted Indonesia’s improved relationship with China as an outcome of Jakarta’s hedging strategy and economic pragmatism. As a recent column in The Economist argued, the latter impetus is related to President Jokowi’s background as a businessman, who views the Indonesian national interest in narrow economic terms, and courts whoever will bring beneficial deals.

But the improved economic relationship is underpinned by more than economic pragmatism or individual leaders’ idiosyncrasies. It is China’s distinct modes of engagement that have been so appealing to Indonesian elites. Modes of engagement, in this context, should not be conflated with economic statecraft more generally, or especially with China’s use of coercive economic measures to get other countries to act according to its wishes. Rather, a wide range of political and economic components constitute modes of engagement—and among these components is a country’s overall approach to economic development.

What has been salient in the context of China–Indonesia relations is that China’s approach to development cooperation with Indonesia dovetails with Indonesian development strategies. More importantly, as I argue here, its approach has evidently provided leeway for Indonesian state elites to pursue not only development strategies on national interest grounds, but also to harness development for their political legitimation goals.

Institutional complementarities

Chinese approach to development cooperation is undergirded by particular institutional features: quick decision making; practical, longer-term financing horizons; and openness to cascading negotiations to accommodate host state leaders’ needs.

These features fit perfectly within the varied landscape of Indonesia’s political economy. Indonesia has sought to defend the liberal international economic order, such as through promoting free trade agreements, while at the same time defying WTO rulings against its unilateral imposition of mineral export bans. It commits to fostering private sector engagement in infrastructure, while making way for its state-owned enterprises to crowd out private investment. It invokes the importance of state developmentalism, but still maintains a conservative fiscal policy—something which has long been a stumbling block for the government to fund the development of capital-intensive industries like nickel downstreaming and battery production.

In short, Indonesia’s development problems have long been entangled in openness and economic nationalism, commodity booms and busts, technocracy and politics. In such a policy constellation, Indonesia requires development partners who have high risk tolerances, and who are flexible enough to deal with the swings of the political and policy pendulum. In this regard China has excelled, thanks to its loose fiscal policy and availability of “patient capital” characterised by greater risk tolerance and more willingness to weather policy volatility in the host country, compared to Western and private capital.

In the case of the Jakarta–Bandung HSR, despite controversies surrounding debt and profitability issues, what has been overlooked is that the salient feature of China’s development financing—giving leeway for state elites to make concessions through cascading negotiations—has ceded Indonesian top state elites political legitimacy.

In orthodox development practice, as easily traced in OECD or World Bank documents, country ownership in a development project has long been the first and utmost major principle. The bottom line is that the recipient or host country must have a direct stake in aid programming and sense of ownership at all stages. In practice, Indonesia has found that multilateral donors and Western governments try to control what gets on the development agenda and project scoping, and are reluctant to cede the agenda in their aid and investment programs to the Indonesian government as overtly as China is.

China’s financing modality, namely equity-based investments such as in the case of the Jakarta–Bandung HSR, regardless of ambiguity in its “business-to-business” financing terms, it is a fact that the Chinese consortium owns 40% of the project and they are also obligated to pay for any cost overruns. A superficial look at distribution of tangible costs and ownership supports the widespread impression that Indonesia is in the driver’s seat, in control of financing decisions and further project development, thus helping boost the political legitimacy of local state elites.

This is a crucial point given that economic nationalism has gained more ground in the country: China’s modes of engagement above all suit the current political climate. This can be sensed in Jokowi’s recent statement at the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in October 2023, where he remarked that one advantage of the BRI was that it offered “…a synergy that provides ownership for the host country to run its national project independently. A sense of ownership is very important for the sustainability of the project.”

Furthermore, at the heart of relations with China is a productivist logic that embraces state-led development, particularly in resource refining and infrastructure projects, with SOEs situated at the commanding heights of the economy. Such productivism holds a view that state strategic goals—although they may include problems of resource access, social, environmental, and political capital—can be understood as preconditions for long-term market-based economic growth that trickles down into tangible social benefits.

While Indonesian SOEs have been the backbone of the economy, they are also notorious for being inefficient, mismanaged, and for being cash cows for political groups. It is an open secret that SOE commissioners are usually the president’s close allies, and that corporate decision-making processes are not insulated from political intervention.

While many Western investors have fled the country in discontent with its resource nationalism and have shied away from engaging SOEs, Chinese companies came to fill the void. As a result, Chinese investments in Indonesia have extended to value-added activities that are now regarded as the cornerstone of national development. Jokowi and his political allies understand that, in contrast to the norm in the past, loans and state capital are being invested today in downstream sectors and infrastructure projects that can boost productivity and reduce dependency. These initiatives are perceived as a critical step in the ladder towards development.

Chinese capital has thereby given Jokowi leeway to create his own legacy, now distilled to the Golden Indonesia 2045 Vision for developed-country status and the broader goal of economic self-sufficiency.

The Morowali Industrial Park, a monument to mineral resources hilirisasi (downstreaming), and the Jakarta–Bandung HSR are just a half of the story. A series of new deals include the Rempang Eco City, a new industrial park to be home to a quartz sand processing plant and solar panel factory that is a joint venture between Chinese Xinyi Group and the Batam Indonesia Free Zone Authority; the China Power-backed 9 gigawatt hydroelectric plant being constructed along the Kayan River in North Kalimantan, meant to power a Chinese-affiliated green industrial park, Indonesia Strategis Industri; a U$1.1 billion electric vehicle (EV) battery factory with the Indonesian Battery Corporation, a joint venture between four major Indonesian SOEs and Korean conglomerates; and a recently-signed MoU between Indonesia’s state electricity company PLN and the State Grid Corporation of China that, along with seven other MoUs, brings total value of Chinese investments in green energy initiatives in Indonesia to U$54 billion.

Looking at this development, it is difficult not to get the impression that the economic interests of Chinese state elites and state companies are comfortably aligned with the Indonesian government’s growth strategy, and vice versa.

Chinese Investment in Southeast Asia, 2005-2019: Patterns and Significance

Sovereignty concerns arise over foreign ownership of critical national assets, and foreign control of service provision in critical sectors.

The JETP deal for Indonesia, while expected to comprise U$20 billion in support, consists of less than 1% of grants, with the remainder being loans, something the Indonesian government believes would set a new loan trap for it and other developing countries. Critics of JETP see it as a mere talking shop that falls short on commitment. As senior cabinet minister and Jokowi’s right-hand man Luhut Pandjaitan lamented in a media interview shortly after a recent visit to Washington, “when I went to Washington last month, we explained it (JETP), they said yes, then I said, where the money is for green transition?…They are just talk”.

China’s financing modality in the energy arena—based on a “business-to-business” approach that directly engages PLN—is seen instead as a more feasible solution in Indonesia. China is indeed in a strategic position: with PLN, the monopoly holder of energy transmission and distribution, being the pivotal stakeholder in China–Indonesia cooperation on greening the energy grid, the project can be easily fast tracked.

Looking ahead

Operating under specific logic of accumulation, Chinese capital can have a distinct impact by helping develop domestic sectors that are otherwise unattractive to global private capital. Of course, this productive model might be more practical than Western-development paradigms, but it is no more participatory or inclusive. Some projects have perpetuated long-held grievances among local populations that see themselves marginalised and dispossessed by the manifestations of Indonesia’ state-led growth strategy.

Indonesia’s National Commission on Human Rights, for example, found alleged human rights violations carried out by joint forces of police, military, and public order officers as part of the efforts to make way for the Eco-City development in Rempang island. With the presidential race heating up, the “China card” might be played again. Yet, just as happened in many countries, the sentiment does not last long soon after a newly-elected leader comes to power. There will always be old answers to new problems, and China will always be around.

As of now, presidential frontrunner Prabowo Subianto—who once used the China issue to attack Jokowi in the 2019 presidential election—has made it clear that he will continue Jokowi’s foreign policy and key national projects. This implies that Chinese investments will continue to ramp up. While politicians are occupied with the Palestinian cause to appeal to Muslim voters, Prabowo showcased his recent meeting with the Indonesia–Zhejiang Chamber of Commerce via his personal Instagram account. On the other side, Prabowo’s opponent Ganjar Pranowo, , offered a rather neutral statement, promising that he would navigate the growing US–China rivalry if he is elected. Meanwhile the opposition-linked underdog candidate Anies Baswedan’s stance on Indonesia–China relations is still unclear, and his team have made fewer comments concerning China.

However, despite the differences in their public statements, it is interesting to see how China is no longer identified in a mere ideological context, but seen as a key development partner. It is still unclear what shaped this development. Is it partly because China’s public diplomacy works well? Or is it because the material interests of elite networks—with whom these three contenders are affiliated—are increasingly interlinked with China?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss