As the 60th anniversary of the establishment of the PRC, China’s October 1st National Day this year was the centre of much media attention both within and beyond the country. But it’s interesting to reflect upon how this festival was viewed within China’s Tai-Kadai speaking minority communities. I was visiting Kam (known in Chinese as Dong (ф╛Ч)) friends in their village in southeastern Guizhou during and after the festival, and here’s an image showing how some of my Kam friends spent the day.

In other words, they spent this important festival doing exactly the same activity that consumes everyone everyday in Kam villages during this period: harvesting rice. Many people who worked on the hillsides in the daytime later watched the lengthy parades and glitzy celebrations on TV that evening, but most described the event using the Kam expression kay da sep or “they hold a festival”. The idea of it being a festival that Kam villagers themselves might share in was never expressed, even amongst younger generations of Kam people who speak Chinese and could understand the TV broadcasts.

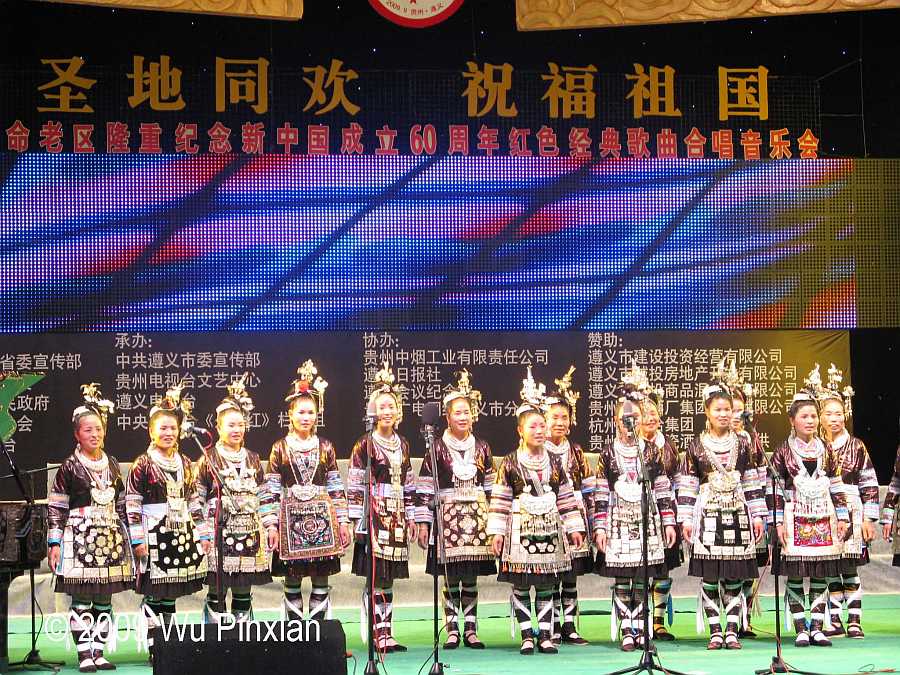

Nevertheless, only a week or so beforehand more than twenty Kam women from this village had been invited to sing at a widely publicised festival in a large city in the same province (Guizhou), winning a prize of over 10,000 RMB (more than AUD$2000). Although this and all other groups participating in the festival had been specifically chosen to represent areas where important meetings for the establishment of the PRC had been held, and although the singing festival once again focussed upon the 60th anniversary of the People’s Republic, only a few of my Kam friends who sang in the performance were aware of or interested in why the festival was held. Here’s an image from their performance.

But the situation was quite different for a big music festival held a few days after National Day in the Kam village of Sao (in Chinese, Zhaoxing шВЗхЕ┤). This Kam festival is celebrated each year on the 15th day of the 8th lunar month, the same day that many Chinese people celebrate Mid-Autumn or Moon Festival (in Chinese, Zhongqiu jie ф╕нчзЛшКВ). As these images illustrate, the well-attended festival involved over a hundred gao gn – ensembles of bamboo free-reed mouth organs that are referred to in Chinese as lusheng шКжчмЩ.

These all-male groups competed in pairs over one long, hot afternoon, moving through qualifying and semi-final rounds to the finals. The judges for the competition sat on a distant hillside overlooking the village, waving a green flag after a below-standard pair of gao gn played, and a red flag (accompanied with great cheers from the crowd below) when the teams were allowed to advance to the next level of the competition. When each pair of ensembles competed the two groups played sets of instruments with different tuning, and they did not make any attempt to co-ordinate their playing except with members of their own group. Despite many Kam friends complaining about the terrible sound of the performance, many Kam people travelled for hours in order to attend.

Although the Kam people I’ve described here had a greater sense of personal investment in this local festival than those sponsored by the Chinese state, it doesn’t mean that Kam people don’t ultimately see themselves as Chinese citizens. But it does suggest that the culturally-determined basis for identity in Kam and other many southwestern Chinese minority groups (which includes a number of Tai-Kadai speaking groups) that has operated for millennia still remains strong. For Kam people, their membership in these groups has been determined by a shared language and culture, not by shared lineage or official registration. Hence even today, festivals like National Day that do not originate culturally from Kam areas are seen as “theirs” not “ours”, and even local Kam festivals whose aesthetics are not considered appealing retain their cultural and social meaning.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss