On December 14, 2007, two days after Chaturon Chaisaeng had given his speech attacking what he saw as a lack of fairness in the run-up to the election of December 23, the provincial election commission (PEC) organized two events that aimed at urging people to cast their votes on election day. In the morning, around 600 students gathered on the square between the provincial hall and sala thai for the opening ceremony of two campaign walks.

Picture 1 shows students from Benjamas 2 school holding a banner that reads “The day we love democracy – Ben 2 joins forces according to the democratic way.” In the background are the two buildings making up the provincial hall.

Picture 1

Readers might remember that this school had referred to the “democratic way” earlier already when it participated in “Celebrating the King” (see post no. 4). This second time, the slogan turned out to be somewhat ambivalent again. Should citizens “love” democracy, and should they do so only on election day? And what was democratic in state schools ordering their kids to interrupt their learning in order to be used as tools by another state organization to pursue its ends? Before the school participated in the event, had teachers organized any debate with their students on whether they should participate in that walk or not? Had the school done anything to make its students aware of the elections by systematically including it as a subject in its regular teaching? Having them wear yellow (!) caps showing the official logo against vote buying only underlines the use of students as advertising tools. Or should one assume that the students demanded or agreed to wear these caps because they had individually come to the conviction that vote buying was a bad thing? Interestingly, the PEC had recruited the students at a time when three MP candidates of the Peoples Power Party were under investigation by the election commission of Thailand (ECT) for having recruited villagers to attend an election rally.

The PEC had invited the provincial governor to open the event from 09.00 to 09.09 hours. As usual in such bureaucratic settings, the chairperson of the PEC first formally reported to the governor about the activity that he was presiding over. Picture 2 shows the PEC’s chairman addressing the governor. Behind him were, from right to left, an official from the PEC office, the director of constituency 2, three fellow provincial election commissioners, and a member of constituency committee 2. Afterwards, the provincial governor gave his remarks (picture 3), which remained in the confines of formal clichés. As the formal act of opening the campaign rally, he banged a gong three times (picture 4).

Picture 2

Picture 3

Picture 4

Obviously, one might ask why the PEC had felt the necessity to invite the governor to open its event. Is the ECT, and thus its PECs, not an independent constitutional organization outside the central state’s executive, including its provincial branches, which are headed by governors residing in the provincial halls? But, then, the PEC’s offices are located in the old provincial hall, and the commissioners and the office staff are all well-embedded in the provincial-level civil service culture. From this perspective, the governor is the highest state representative in a province, for which reason it is an honor to have him preside over one’s function, and one must also give him honor. As a result, a big part of all provincial governors’ work is presiding over all sorts of ceremonies. This also includes the private sector, after all, even nowadays newspapers often refer to governors as “pho mueang“-the father of the province.

For the campaign walk, the students were divided into two groups, walking different routes. Both groups were led by brass bands to make people come out of their shops and look what was it all about (picture 5). The students carried banners provided by their schools and those from the PEC (picture 6). At the end of the walk, a PEC official waited with a car to recollect its banners. As the picture indicates, the second route somehow lacked a potential audience. The first route, passing along the town’s old center, was more populated.

Picture 5

Picture 6

Anyway, it was surprising to note that the walks were not accompanied by an advertising truck, nor by teachers using megaphones to get the electoral message across. Moreover, no information material on the election was distributed to the people, who probably could hardly read the banners carried by the students passing their shops. Therefore, the entire undertaking was a lot less effective than it could have been. As a friend noted, “This is merely ceremonial.” She also produced one of the caps given to her by one of the participating students. One wonders whether all these tax-financed caps will ever be worn again beyond these brief walks.

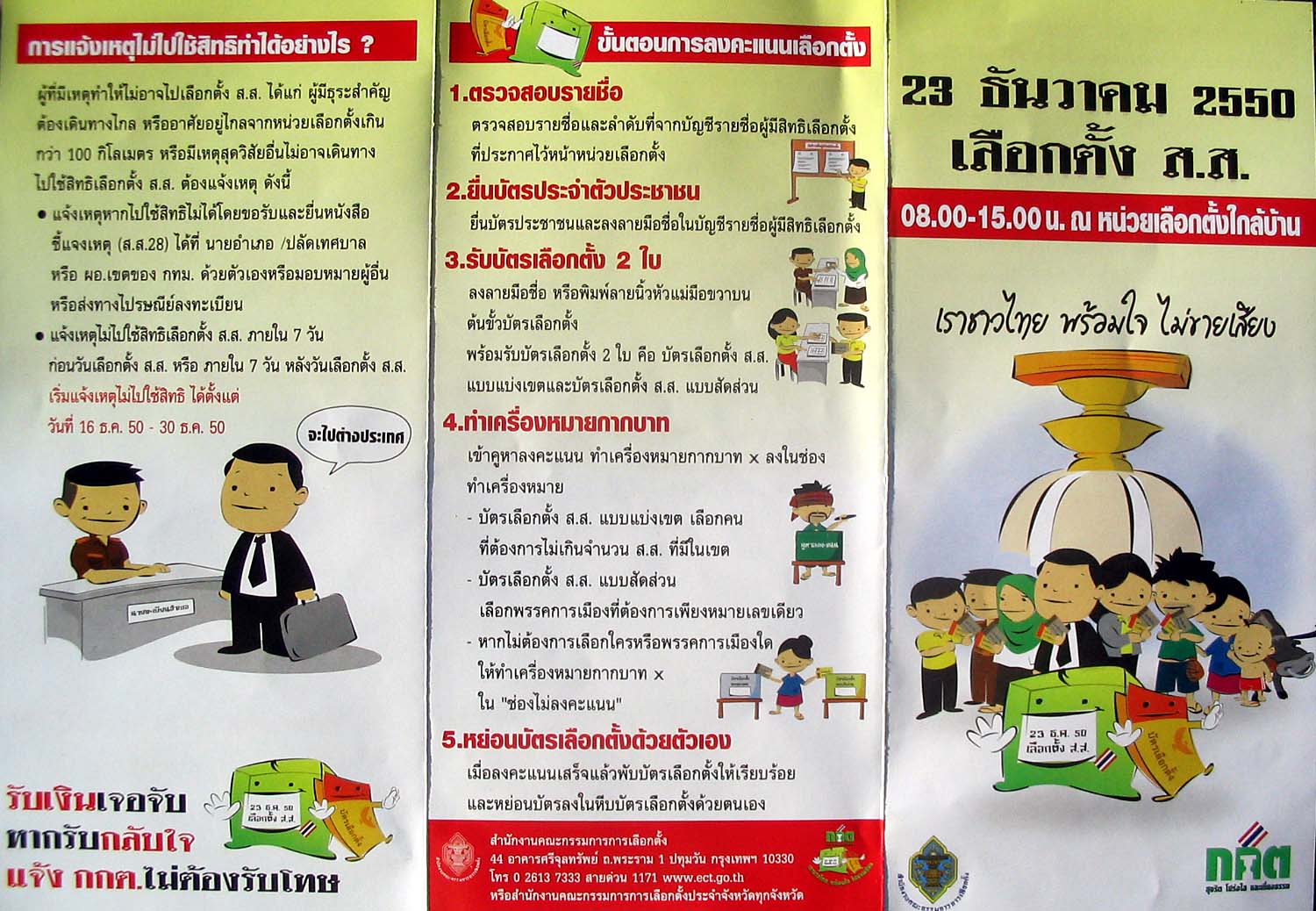

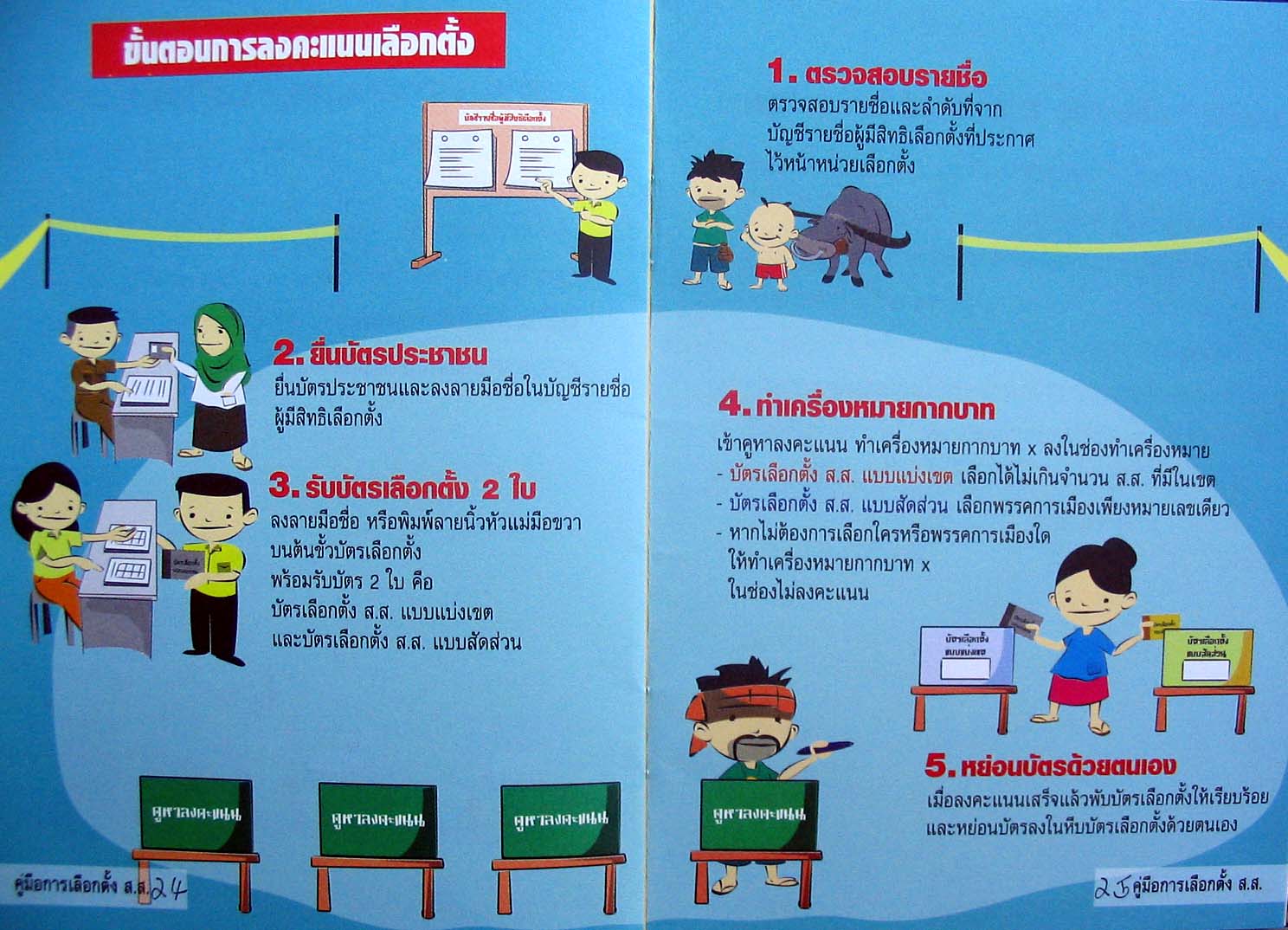

In fact, the PEC does have information material for distribution. For example, there have been stacks of leaflets in the office informing people about the election procedure (picture 7). More recent are the “election manuals” that provide some more detail. Picture 8 shows the cover page, while picture 9 reproduces a double page showing the procedure in a polling station. Perhaps, people along the walk routes were not the intended target voters?

Picture 7

Picture 8

Picture 9

In the evening, a huge stage was erected at the same place where Chaturon Chaisaeng had made his speech. The PEC’s version was billed as a luk thung (country music) show with award-winning students from Benjamas 1 school. However, it turned out to be more like a deafening big band with girls and boys doing Las-Vegas style dancing in fancy costumes. This contrasted nicely with what one election commissioner complained about in his speech from the stage, namely the danger western influences on Thai school children posed for Thai culture. Picture 10 shows a small number of members of the troupe at the end of its rendering of the King’s official birthday song, “The father of the land.”

In terms of social composition, the PEC audience was rather similar, or perhaps slightly lower, than that of the Chaisaeng event (picture 11). About 200 people attended the show, compared to about 400 who listened to Chaturon. The PEC had neither done any public relations for its event nor provided any chairs, for which reason the big space in front of the stage remained empty. According to a source, the PEC lacked budget for organizing chairs, and also thought that the ground was suitable for sitting. The audience, though, obviously thought otherwise.

Picture 11

The show was officially opened by a speech by the PEC chairman (picture 12). While the students performed their first singing- and dancing acts, the PEC’s people and representatives from three political parties, who had responded to the PEC’s invitation (all to be among the electoral “losers”), figured out how to arrange the scheduled five-minute statements by the election candidates. Picture 13 shows the chairperson of Chachoengsao’s Democrat Party branch (holding up two fingers) with one Democrat candidate, Phatachakrienchai (to the left), while the two candidates in white jackets are from the Chart Thai party. The official in the yellow polo shirt is a member of constituency committee 2 and was there to control the speaking time. Picture 14 shows Democrats Chalee and Phatcharakriengchai on stage.

Picture 12

Picture 13

Picture 14

Finally, the Rajaphat University’s public administration department had put up a banner – far from the stage and thus seen by few – asking voters not to elect cheating and vote-buying candidates (picture 15). Curiously, the headline of the text was “prot fang ik khrang” (please listen again). This was the infamous phrase used by the coup plotters when they made their various announcements on television.

Picture 15

One wonders whether this choice of words indicates the lecturers’ endorsement of the past coup and, should the voters elect “cheating and vote-buying” candidates, an advance endorsement of a future military takeover.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss