On December 15 and 16, 2007, advance voting took place. This concerned two groups of people. First, voters who live in Chachoengsao but have their residence registered in a different province. They could vote in Chachoengsao for candidates running in their home provinces. However, they had to apply with the provincial election commission (PEC) in Chachoengsao to be included in a special voter roll, while their names were deleted from the rolls in their original provinces. That meant that if they did not turn up during advance voting, they could not travel home for voting in their original provinces on December 23. Rather, they would be counted as not having done their duty-since voting is compulsory in Thailand-and would have to inform the PEC after the election of the reason that they had not voted. Failing to do so, or giving a reason deemed invalid by the PEC, would result in the loss of certain rights, such as being able to run in all sorts of elections (House, Senate, local governments, kamnan, village headmen). These lost rights would be reinstated with the next election in which they voted.

Every province had one central polling station for this purpose. Picture 1 shows a banner saying that this was the central polling station for nok khet changwat (outside of the province). In the election of February 2005, sala thai, the open multi-purpose hall opposite the provincial hall, was sufficient to do the job of advance voting for all provinces outside of Chachoengsao. At that time, only 348,739 people had registered countrywide, and only 143,153 (41.1%) of them actually voted. This year, the figure had jumped to 2,095,410, of who 1,838,889 (87.75%) came to cast their ballots. In Chachoengsao, 24,838 voters had registered, of whom 20,612 (82%) turned up in equal numbers on both days.

Picture 1

As a result, a large number of tents had to be erected on the square between sala thai and the provincial hall, housing at least 24 separate polling units for different numbers of provinces in the outer columns (picture 2). Picture 3 shows the sign for unit no. 18 serving the provinces of Yasothon and Roi Et. The corresponding inner columns of tents were organized on the basis of the eight groups of party-list provinces. Accordingly, each group had at least three boards voters had to consult (after they had wandered around the tents to look for their group of provinces since there was no information at the entrance of the area about which tents served which provinces).

Picture 2

Picture 3

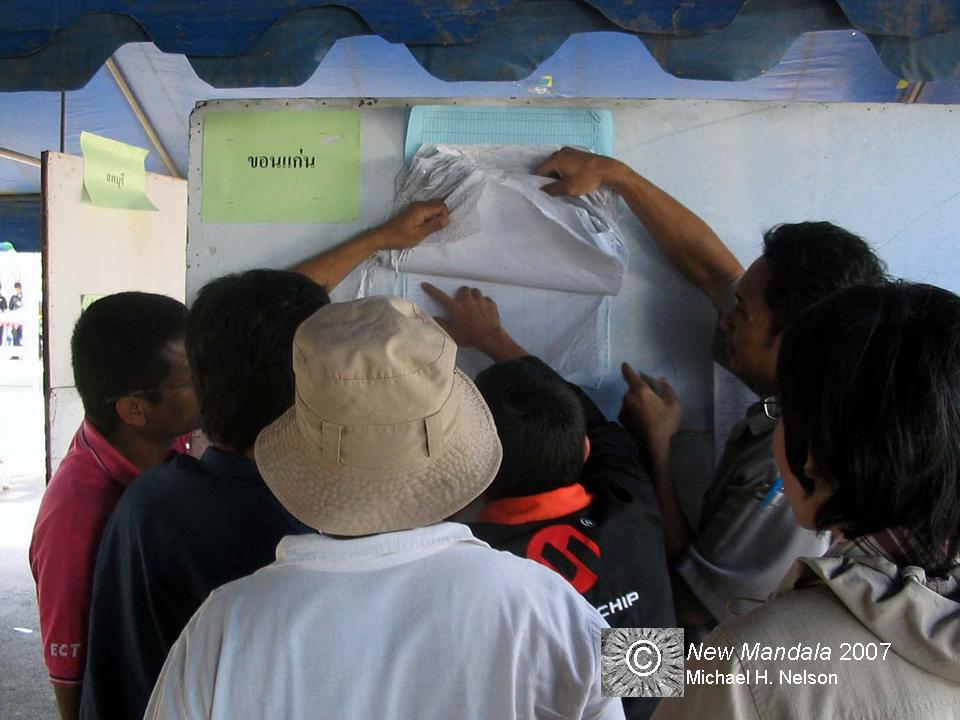

First, voters had to find their names on the voter rolls, and then note down the number of their provinces, constituencies and ranks on the voter rolls so that the officials at the polling unit would not have to waste time in locating the names on their print-outs of the voter rolls. Since the names were alphabetically ordered only within the constituencies and since their numbers had changed over the last three elections due to the reintroduction of multi-member constituencies, this would often cause some problems. When I was talking with an election official near to one such board, we observed a factory worker going for some time through the thick list, while people were waiting behind him to have their turns. Finally, he turned away with an angry face saying, “I can’t find it.” This prompted the election official to approach him with an offer to help. Picture 4 shows the official holding up the voter roll with his left hand and the worker holding it up with his right hand, while another voter is still searching for his name.

Picture 4

Generally, the PEC had tried to facilitate the voters by placing officials and school students near the boards so that they could help voters identify their constituency numbers and ranks. The young women who has been helping my landlord for many years had her first ever try at voting in an election delayed for one day. As she told me, she went to sala thai on the morning of the first day, which also saw factory busses sending workers to the polling station. Though she was able to find her polling unit and the board with the voter roll, there was such a great number of people that she could not even get close to it to look for her name. Thus she had returned home. One day later, everything went smoothly. A student was on hand to look for her name; she said that the procedure was “saduak” (convenient).

Her voting behavior was interesting since she split her vote, choosing the Democrats on the party-list system and Chart Thai for the two seats in her constituency back in Ubon Ratchathani. She said that she had voted for the party that she liked, especially for Abhisit Vejjajiva, based on the “khomun” (data) that she had gained through her daily reading of the newspapers. In addition, she disliked TRT, and Samak being the nominee of Thaksin. She added, however, that many of her friends from the Northeast, even the one who accompanied her to the polling station, still liked Thaksin and thus voted for the People’s Power Party (PPP). Regarding the constituency vote, she pointed to the fact that she has been living in Chachoengsao for so many years already that she had no idea whom to vote for. Therefore, she had called her mother in Ubon. She gave her the advice to vote for the Chart Thai candidates, because they had done many good things for the area where the family lived, and they had always been helpful when help was needed. Since this young women had no better idea of who to vote for in her home constituency, she followed her mom’s suggestion.

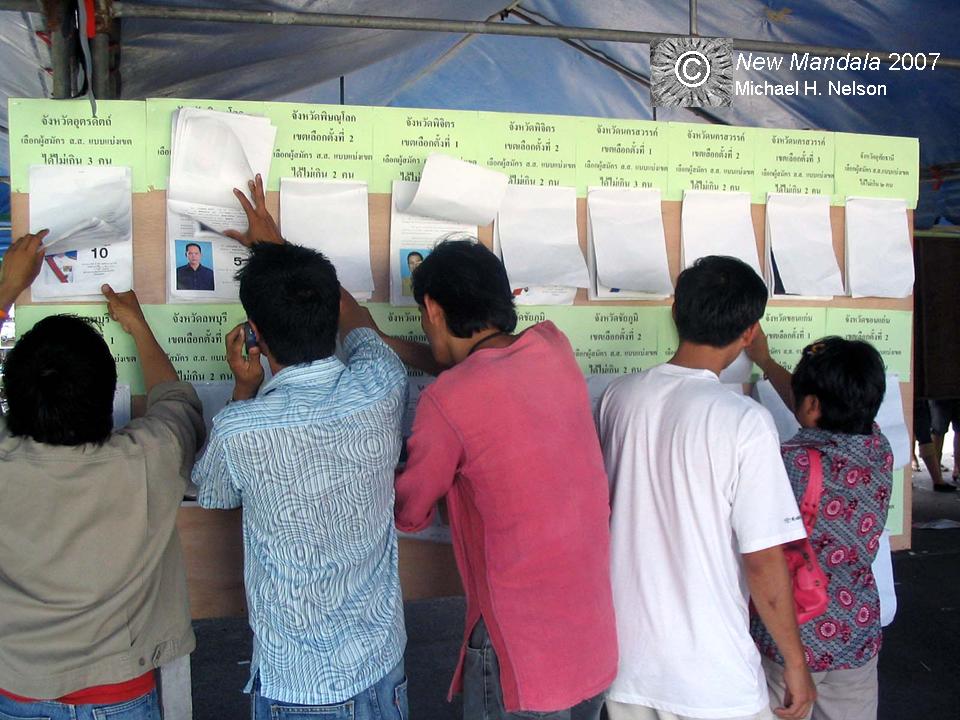

Many voters certainly had similar problems. Picture 5 shows some of them checking out the candidates in their home constituencies in Uttaradit, Phitsanulok, and other provinces on the second board. One would like to imagine that the young man holding the telephone was phoning some contact person in Phitsanulok’s constituency 1 in order to make sure that he got the right candidates and numbers. For a detail, readers might note that the last line just above the bundles with the candidates’ pictures reminded voters for how many people they could vote in that particular constituency (mai koen 2 khon, mai koen 3 khon-not more than 2 candidates, not more than 3 candidates). The thirds boards with the party-list candidates were less crowded, because voters would only need the parties’ numbers. These were the same in the entire group of provinces, while the numbers for candidates running for the same parties in the individual provinces, and even constituencies, would mostly be different.

Picture 5

As for the high number of voters who registered and turned out, some commentators interpreted this an a sign of heightened political awareness, and as an indicator of a 70%-plus turnout on December 23. This might or might not be the case. It is noteworthy, however, that election day and the new year holidays are unusually close together, in fact, only three or four days, and that election day precedes the new-year break. It might have just been to time-consuming and costly for many voters to do their trips home twice in such a short period of time. One policeman distributing the slips to the voters for noting down their province, constituency, and rank number at the crowded polling station for Surin province suggested that time and cost saving considerations were the most important explanations for the high number of people making use of advance voting this time. Another policeman, originally from Buriram province, suggested that there were two possible reasons, namely political awareness and the mentioned pragmatic considerations. When I started a follow-up question with “And the second reason…”, he completed it with a smile by saying “…has more weight.”

Unlike voters in ordinary polling stations, those who used the cross-provincial voting procedure received an envelop-the ECT’s form for it is “So.So. 39”-with their two ballot papers. After voters had marked them, they had to put both ballots into that envelop addressed to the director of the relevant constituency committee. Voters would fill in the name of the province, the constituency number, and the postal code. Finally, they would seal the envelop and put it into one single ballot box. After voting had closed, the envelopes would be sorted, put into bags, and handed over to the Thai Postal Company to send them to the respective provinces for counting after the polling stations will have closed on December 23.

The second group of people who were allowed to vote in advance were those who had their house registrations in Chachoengsao but could not vote on December 23. These voters did not have to register in advance. Rather they would simply go to their dedicated district-level advance polling stations, mostly the district administrations’ meeting halls.

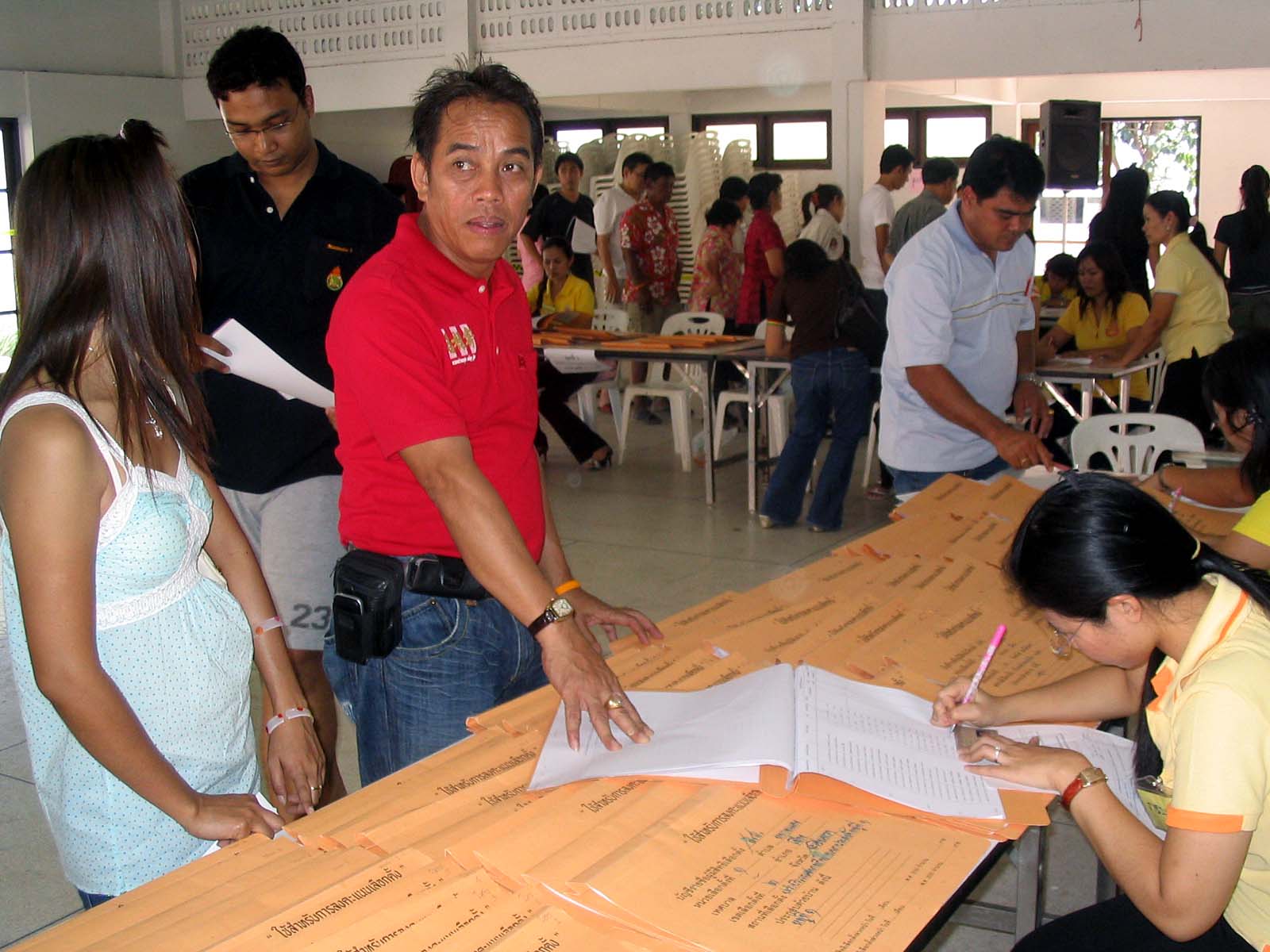

The procedure can be seen in the following series of pictures. It features a local stringer for TiTV, The Nation, and others. He also used to be a deputy executive chairperson of a tambon administrative organization and hua khanaen (vote canvasser) for a number of MP and Senate candidates. Some weeks earlier, he had told me that he had resigned from his local government position and stopped his canvassing activities, because he wanted to keep on reporting on events and thus had to avoid making candidates suspicious of his neutrality (in my book on Chachoengsao, he can be seen on plate 21, standing in the center checking the results of the election of March 1992). I met him in the polling station by accident. I had just arrived to have a look and was standing near the files with the voter rolls, then for some reason turned around to find him grinning at me.

Picture 6 shows the banner saying that this was the advance polling station within the constituency. In this case, it was the meeting hall of the amphoe mueang (central district) district office. Picture 7 shows the reporter filling in the form supervised by a policeman. Amongst other things, this form also required the applicant to fill in his rank number on the voter roll, the number of his original polling station, and the name of the tambon. Since he had not known the procedure, he had to walk to the entrance of the district office compound where tents had been erected with the voter rolls of all the polling stations in amphoe mueng (except for those five tambons that belonged to constituency 1), in order to search for the required data. The main purpose of these tents (picture 8) had been to enable voters to check whether their names appeared in the voter rolls, and whether additions or deletions should be made. For the same purpose, the rolls were also displayed at the provincial hall and at the designated polling stations.

Picture 6

Picture 8

In picture 9, our voter points to his name on the voter roll of his original polling station. If I remember correctly, his rank number was 701-normally, a polling area should encompass between 700 and 800 eligible voters. Otherwise, if there is a high turnout, polling stations might get into trouble processing the voters, because they are open only from 08.00 hours to 15.00 hours. In the 2005 election, I had observed one polling station in Bang Nam Prioew district, which had a long queue of voters right from the opening of the station until its closure. Thus, the chairperson decided to let all those voters use their rights who had turned up until 15.00 hours. In fact, that was not permissible.

Picture 9

Picture 10

When the reporter had reached the two officials who would decide about his application, he was asked to fill in a reason for his request to vote in advance (picture 10). The form offered boxes to tick for three pre-typed reasons. First, on election day, he or she would have to travel outside of the constituency. Second, the voter had received an order from state authorities to perform duties outside his or her constituency. Third, the voter was assigned to work in a polling station other than his or her own. Finally, there was the category “others specify…” Since none of the three main reasons applied, he put in-as expected-“On election day, I will have to report about the election” (not a real quote). For official use, the chairperson of the committee had to tick “permit” or “not permit.” Of course, basically all requests were decided positively.

Only a few steps away, a table with a set of original polling-station voter roll files were placed. An official would draw the respective file, look up the name, cross it out, and fill in the number of the identification card (picture 11). Afterwards, the official would turn around the file for the voter to sign his name (picture 12; the girl to the left of the reporter is another voter waiting in line and unrelated to him). At the end of the table, another official handed out the two ballot papers and let voters sign their names on the slips that would remain as evidence in the booklets containing the ballot papers (picture 13). The last step, after the reporter had made his mark on the ballots in the polling both, obviously was to put his two ballots in the two ballot boxes, one dedicated for the constituency vote, and the other for the proportional vote (picture 14).

Picture 11

Picture 13

Picture 14

After the end of this two-day advance voting exercise, the ballot boxes had to be stored in a secure place, for example in the office of the director of the PEC office, to be opened and counted only after polling stations have closed on December 23.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss