A letter appeared on Yok’s* desk one morning, inviting her to an event at the state institution where she works. The event was a guest lecture entitled “The Monarchy and Thailand” by a group called the “904 volunteers.”

“What is this? Is it compulsory?” Yok asked, waving the letter in her hand.

“Why? You don’t want to go? Isn’t the topic interesting?” teased her friend and colleague Bell.

“Shh! Are you crazy?” giggled Yok, looking over her shoulder. “Who are these 904 people, anyway?”

“Haven’t you heard?” asked Bell, who follows politics and is a fan of Future Forward Party. She leaned closer and told Yok about a news article she had read describing the royalist “Volunteer Spirit 904.”

According to a Reuters report, around 3,000 Thais from the public sector have volunteered to attend intensive “boot camps” at a military base in Bangkok, where they wake up at 5am to do light exercises, practice military salutes and study the history of Thai kings. The training program can last up to six weeks and ‘graduates’ are tasked with promoting the monarchy at seminars like the one Yok and Bell were invited to. In human resource management theory, this approach is called ‘training the trainer,’ or cascade training.

To reach the thousands of employees at Yok and Bell’s large state institution, multiple seminars were offered over several weeks. Although there was never any explicit pressure to attend one, it was tacitly understood that all staff should do so. The two friends dutifully chose a date and went together to their workplace’s large function hall, where they signed in with their staff ID and joined an audience of around three hundred.

Once everyone was seated, around ten of the 904 Volunteers literally marched into the hall, wearing khaki pants and shirts with yellow neckerchiefs. They paraded around in a highly militarised style, before bowing and then prostrating themselves in front of a portrait of the king. The audience was then asked to stand, with men bowing and women performing a curtsy towards the portrait. In this particular session, attendees were able to sit wherever they pleased, but later sessions separated men and women into two sections to allow for a more aesthetically pleasing—and photogenic—display of bowing and curtsying. Later sessions also saw uniformed soldiers keeping watch over proceedings.

The 904 Volunteers opened by introducing themselves. Several were from government ministries, some from state enterprises. A couple were staff from the prime minister’s office and there was one policeman. Then, starting with the Ayutthaya era and continuing to the present day, they recounted a well-rehearsed history of Thailand from a royal-nationalist perspective. They extolled the many achievements and positive attributes of all the Thai kings against rousing background music. Yok was already more than familiar with much of the content from her school days.

The lecture also examined the many unique and wonderful aspects of Thai culture, which the 904 Volunteers said is being eroded by too much Westernisation. The audience was told that Thais nowadays are more familiar with Western culture than their own. To exemplify this point, a slide of the Mona Lisa was shown to the audience, who was asked if they knew the name of the painting and artist. They did, of course.

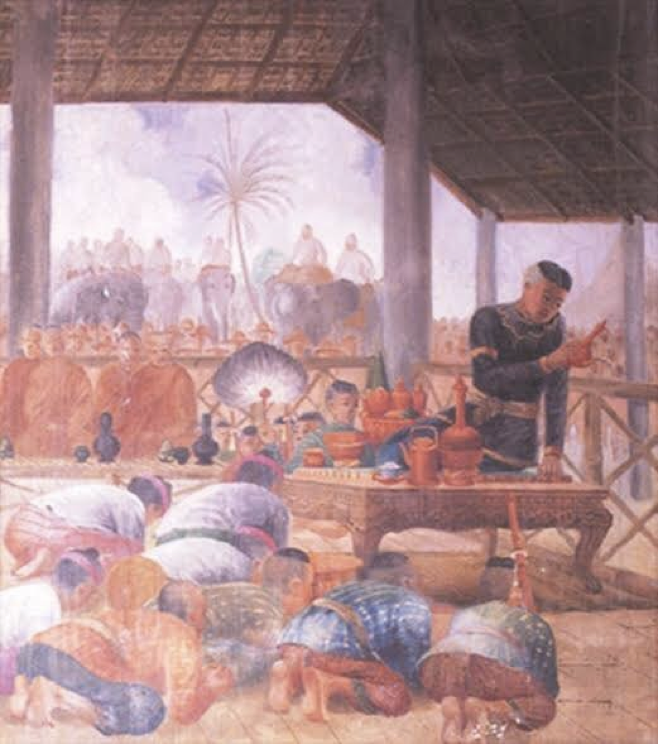

A painting of King Naresuan was then shown, which was not an image many in the audience were familiar with, including Yok. The portrait shows Naresuan pouring holy water on the ground as a declaration of Ayutthaya’s emancipation from the Burmese Toungoo Empire. The speaker lamented that Thais are so unfamiliar with their own culture and history that they didn’t even know this painting.

(Chosen for its perfect blend of royalism, nationalism and militarism, a film of King Naresuan’s life was given free screenings across Thailand just after the 2014 coup. The film was one of a series of six directed by a minor royal, Prince Chatrichalerm Yukol, and also happens to star Colonel Winthai Suvaree, the spokesman of the NCPO coup group.)

King Naresuan pours holy water on the ground

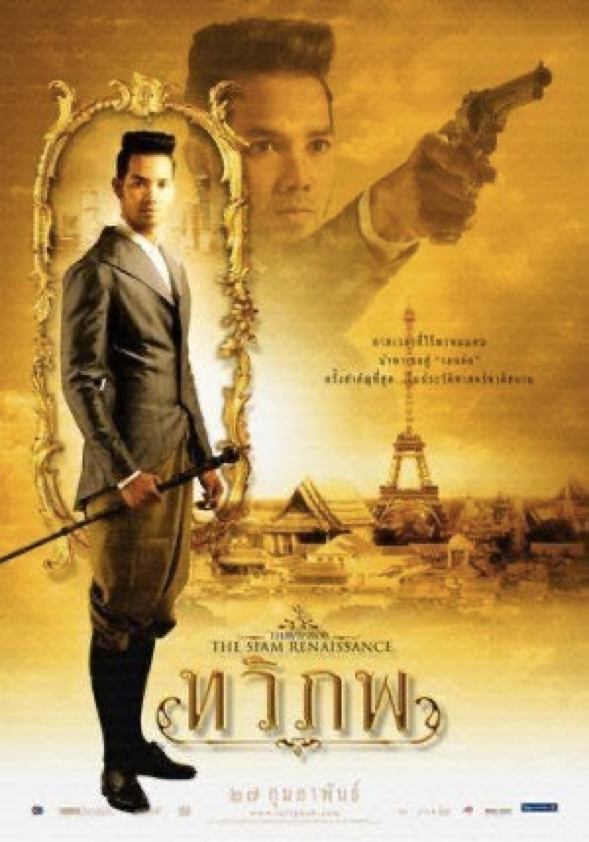

Another 904 speaker then showed a clip from the 2004 film The Siam Renaissance (ทวิภพ), a historical time-travel fantasy with themes of nationalism and anti-colonial struggle. At one point, the film (and the 1986 novel from which it was adapted) imagines an alternative history in which Siam was colonised by the French, who build the Eiffel Tower on its soil. This humiliation is averted, however, and Siam remains the only country in the region to maintain its independence.

Thongchai Winichakul considers the story as exemplary of the official Thai history that, “with skilful diplomacy, the Chakri monarchs saved the country, though not without sacrifice and pain.” The original novel was written by Wimon Chiamcharoen (pen name: Thommayanti), an outspoken right-winger who campaigned against the student movement after the Thammasat Massacre and coup of 1976. She was given the royal title of Khun Ying by King Bhumipol in 2005.

The Siam Renaissance (ทวิภพ)

The Reuters report on the 904 Volunteers quoted a source as revealing that one measure of the success of the seminars was whether or not the speakers made the audience cry. Yok told me she felt amused at first, then bored, and eventually annoyed during the three-hour lecture. But she said others seemed genuinely moved. At least one lady who sat nearby her was indeed, to quote from the Reuters article, “inspired to tears.”

And this is the most dangerous part of the program: that it so starkly highlights and exacerbates divisions in Thai society. While some Thais look to the future, others cling to the past. While some talk of constitutions, others talk only of kings. The cascading waves of royal-nationalism that wash right over some can flood others with powerful emotions.

Is the era of “Red versus Yellow” over in Thailand?

ยุคของ “แดง ปะทะ เหลือง” ในประเทศไทยจบแล้วจริงหรือ?

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the informants.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss