Photographs captured by C.J. Kleingrothe have gained widespread acclaim for their exquisite representation of colonial life in Sumatra’s plantations and society. Yet little is known about the life of Kleingrothe and the narratives that inspired his work. This article aims to delve into his life and explore the stories behind his photographs, shedding light on their context and historical significance.

The birth of the tobacco city

Following the abolition of the cultuurstelsel policy in 1870, the Dutch colonial government implemented a liberal economic system in the Dutch East Indies that allowed private companies to exploit the colony’s resources. Seeking to establish the Sumatran Sultanate of Deli as a rival to neighbouring sultanates, the Sultan of Deli granted European planters a long-term, low-cost land concession to cultivate tobacco. With the virgin land available, some pioneering planters took the opportunity to set up tobacco plantations. The tobacco leaves produced in Deli quickly gained popularity and were highly valued as cigar wrappers in Europe and the USA. The era also marked the availability of commercial photography.

How Indonesian studies’ “brand needy” lets Australian students down

There is a strong case for supporting the study of Indonesian history and cultures in Australian universities.

Meanwhile, G.R. Lambert & Co. photography studio was founded in Singapore in 1875 and expanded throughout Southeast Asia. In 1885, they opened a studio in Medan at the request of Deli plantation owners, with Heinrich Ernst becoming their first photographer there. In 1886, Hermann Stafhell, a Swedish photographer residing in Singapore, was invited to capture images of the new railway tracks and station in Medan.

Stafhel and Kleingrothe

Carl Joseph Kleingrothe (1864–1942), also known as Karl Josef or Charles Joseph, was born on September 24, 1864, in Krefeld, Prussia (northwest of Düsseldorf). Kleingrothe was 23 years old in 1888, when Lambert hired him as a photographer in Singapore and subsequently travelled to Medan.

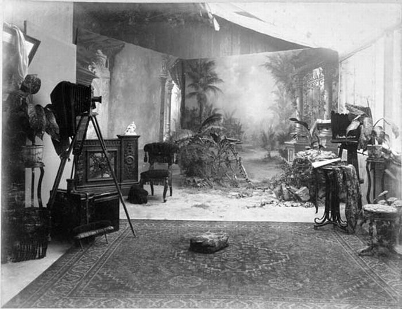

Kleingrothe quickly found plenty of work capturing images of the building of the city of Medan, its infrastructure, and the tobacco culture in the area. In 1889, Kleingrothe and Stafhell established their own photography studio. Their plate camera and tripod captured photographs for tobacco companies, the Deli railway company, official government events, and private individuals.

Stafhel and Kleingrothe’s studio had natural light that was entering through a large window. The backdrop they used portrayed a tropical scene, complete with palm trees and accompanied by props such as a chair or table and cloth draping. (Source: Tropenmuseum, CC license).

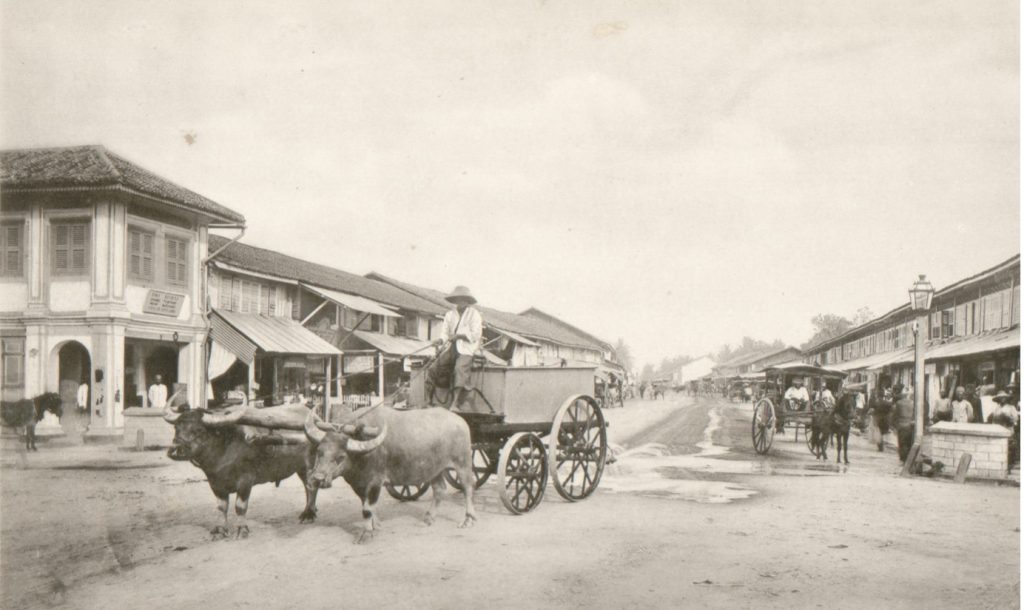

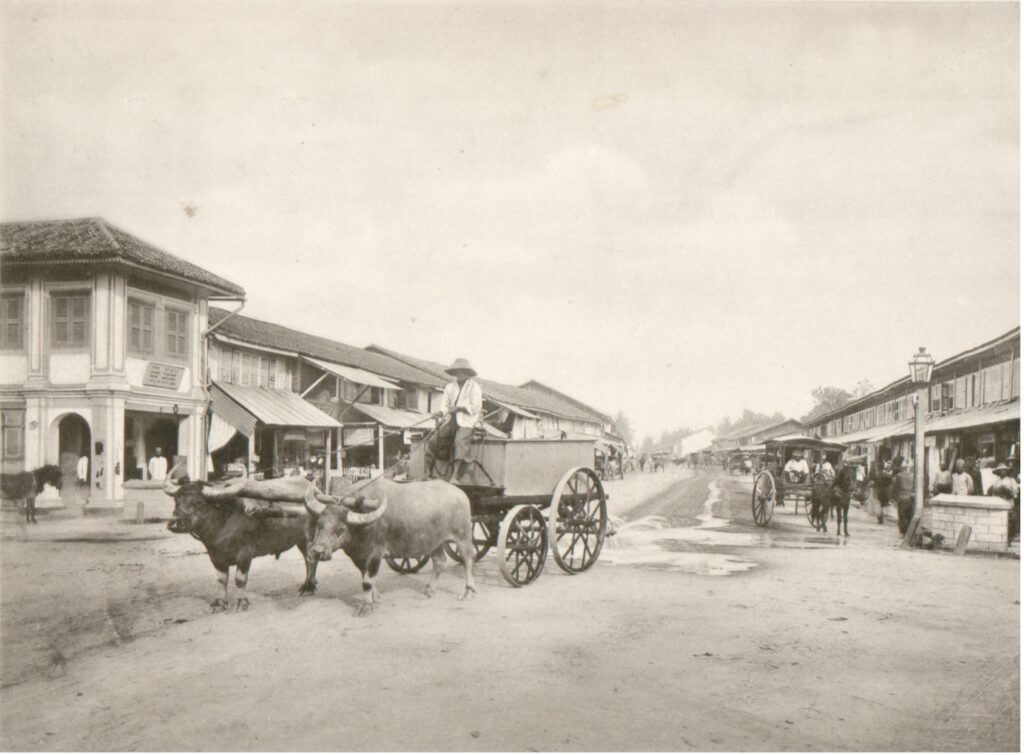

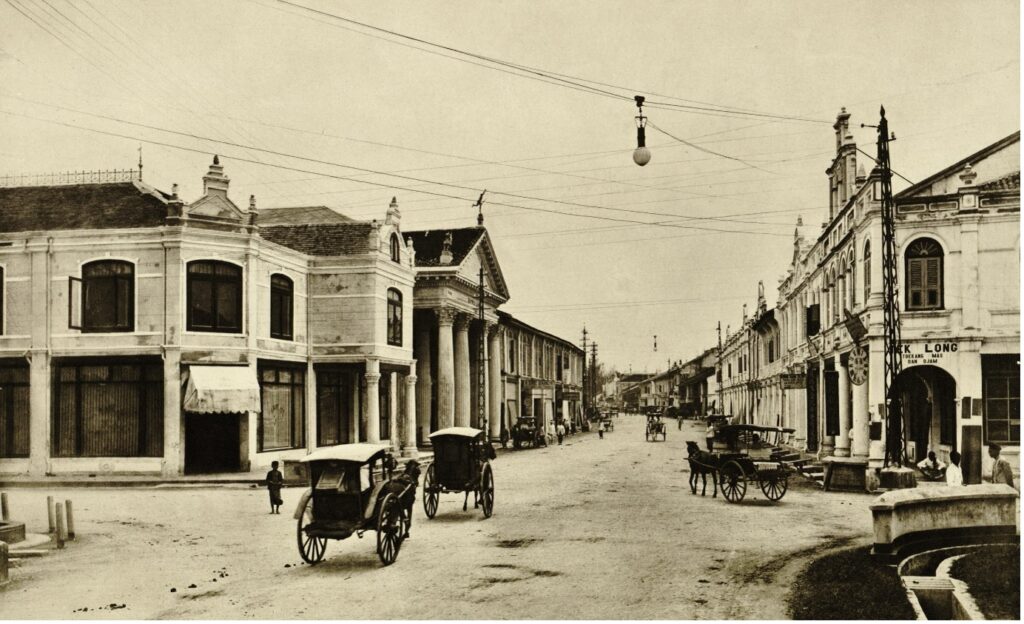

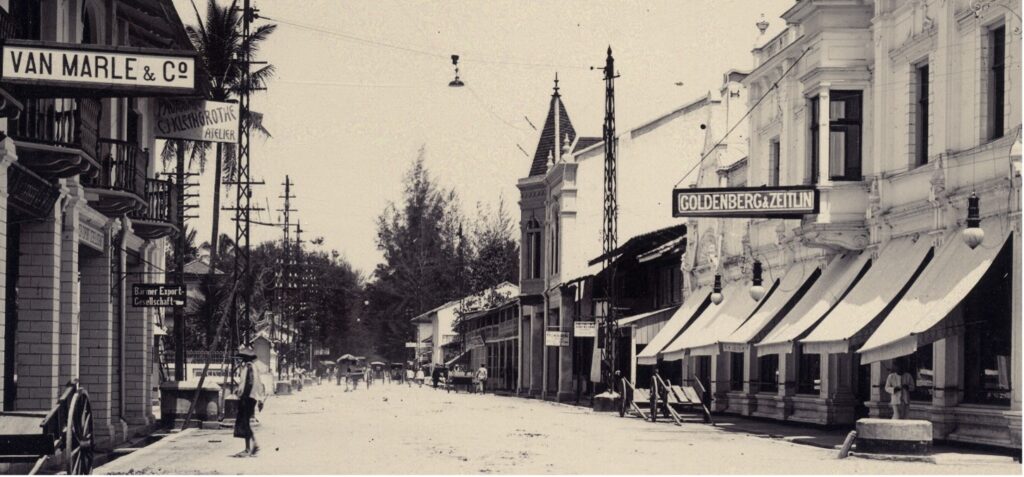

Due to their exceptional work, Stafhell and Kleingrothe became renowned in Medan and the region. Their albumen and gelatin silver print photographs showcased the colonial ideal, emphasising the Deli pioneers’ spirit of conquering the wilderness and bringing modernity in the region. They arrived in Medan when Kesawan was still a village of wooden shops on the dirt road. Within a few years, Kesawan was transformed into a central shopping area.

Kleingrothe Atelier

In 1897, Stahfell decided to move to Singapore, while Kleingrothe chose to remain in Medan and established his own studio, the Kleingrothe Atelier. The studio occupied the upper floor of three shops in Kesawan with natural light from a vertical frosted glass wall, controlled by sliding and folding curtains.

Kleingrothe Atelier (on the left). It is on the second floor of Kesawan, the building on the corner of Marktstraat (now Jl. A. Yani III) )(KITLV 181257)

Besides photography, Kleingrothe was an inventor. In 1904, Kleingrothe filed an invention of the design of roofing tiles in Singapore. Working in a harsh tropical environment, Kleingrothe offered the German photo paper industry a prize of a silver beer goblet worth 300 marks to produce durable photographic matte papers.

Kleingrothe had a busy business and fulfilled his duty as a toekang potret as defined by Paul Faber: studio photograph, commissioned photograph, and photographs in aid of science.

In 1902, Johannes van den Brand, a lawyer in Medan, released an explosive booklet, De Millioenen uit Deli, or the Millions of Deli. It exposed the appalling conditions of the workers and systematic abuses by the Dutch planters to the plantation coolies. The public in the Netherlands was deeply shocked by the account of the atrocious treatment of the plantation labourers.

To counter the negative publicity, Kleingrothe released an album of the Arendsburg tobacco company. De Sumatra Post, 10 November, 1903, reported:

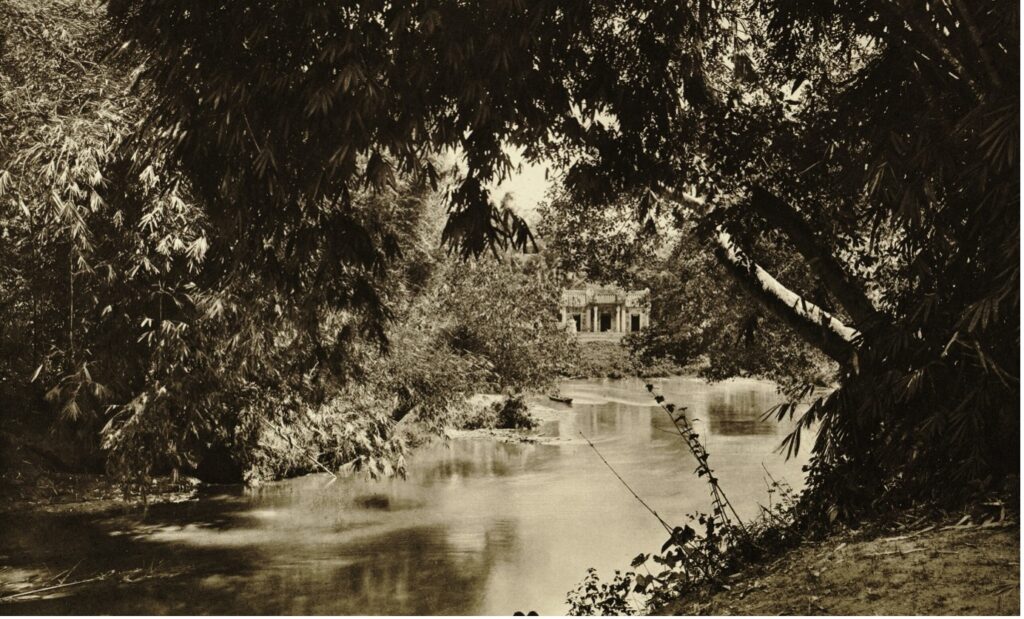

For example, the picture “Chinese Temple of Kloempang” which was a small temple but the whole look, because of the beautiful composition, the beautiful distribution of light and shadow, is reminiscent of a scene from “A Thousand and One Nights”. The “Park with Javanese houses” is an image that we would like to have in the Groene Amsterdammer magazine.

If the magazine would reproduce this image from the real world as a counterpart to the previously spread picture, which was only based on lies, then many in Holland too, who now still regard Deli as a land of coldness and brutal violence, would learn to see that they were a bit too one-sidedly informed.

Kleingrothe was called for visits, farewells, sports events, and parties of important guests and officials. He made albums for large tobacco companies and was a reliable promoter. The Deli tobacco plantations need to have these positive images. At the Semarang Exhibition in 1914, the Deli tobacco association made an effort to display “humanly speaking complete picture of the tobacco culture in Deli”.

In these photographs, the hidden reality of social hierarchy becomes discernible, shedding light on the contrasting positions occupied by European assistants and Asian labourers. One striking example is captured in the picture depicting coolies sorting tobacco in a barn. The Chinese coolies were portrayed engaging in strenuous labour, while the Europeans, positioned higher than the workers in their white attire and holding a stick, emanated a sense of authority.

Coolies sorting tobacco in a barn of the Amsterdam Deli Company in Medan, Sumatra (Kleingrothe ca 1900), KITLV 78329.

Another captivating photograph showcases the house of a European assistant amidst the tobacco fields. The well-maintained tobacco crops and the diligent coolies collecting leaves were beautifully captured. An ox cart, driven by an Indian worker, transporting the harvested leaves. In the distance stands the European assistant in front of his house. Though smaller in the frame, his attire and demeanour exude a sense of dominance.

Kleingrothe’s photographs captured the nuances of the interactions between Europeans and Asians. One particular image portrays two Europeans leisurely seated and enjoying beer, projecting a sense of relaxation and dominance. In contrast, positioned in the background, a Chinese servant fulfilled a subservient role.

Two European men drinking Beck’s beer with De Sumatra and a Chinese attendant at the back serving beer (Kleingrothe circa 1890). KITLV 155291.

Photos of exotic people

Kleingrothe’s photography studio attracted a diverse clientele, including Europeans, Chinese, and Sultans. He captured photos of people of different ethnicities in Medan, including Malay, Javanese, Indians, and others. However, Kleingrothe’s photographs often depicted the local people in a stereotypical and exoticised manner. Photographs of indigenous people became popular postcards in the Dutch Indies, often labelled as “Indische Typen” or Indonesian types. One notable example is the photograph of a Batak man, taken in Kleingrothe’s studio, and described as an ex-cannibal. Kleingrothe used this fierce-looking man with a primitive appearance as an advertisement for his business.

Kleingrothe also embarked on a journey to Batak Karo villages, aiming to document the lives of the indigenous. Through the support of the plantation administrator and the village chief, he gained access to one such village. However, it took three days of persistent effort, employing a ruse and the assistance of the chief, to coerce some of the women to participate in the photograph. The women, some minimally dressed, were arranged in their traditional house, to portray an image of their cultural practices and way of life. His photographs ended up in the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin as a reference on Batak people for anthropologists and ethnographers.

These photographs project an image of the East Indies as an exotic place with adventure, highlighting the supposed “civilising mission” of the Dutch.

Batak women pounding rice in in Kampong Bandar Bringin, Sumatra (Kleingrothe ca. 1880), KITLV 101317.

C.J. Kleingrothe

Kleingrothe’s photographs were used to create albums and postcards that documented the landscapes, architecture, and people of the region, becoming popular collector’s items. The Austrian Geographical Society purchased his photographs of the tropical forest to showcase exotic tropical plants, such as banana trees, which were unfamiliar sights in Europe.

In 1903, Kleingrothe brought his negatives to Munich to be transformed into photogravure prints, resulting in ground-breaking albums such as the Deli Maatschappij and Sumatra’s Oostkust. Kleingrothe established himself as an artistic photographer. He even gifted a copy of his album, bound in the skin of a crocodile, to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, who expressed her appreciation. By the 1920s, his albums were highly valued, and they can now be found in museums worldwide.

Kleingrothe departed from Medan for Europe in 1915, possibly due to the war and associated anti-German sentiment. While Kleingrothe captured many European working in Medan, I cannot find any picture of him and little is known about him. He lived and made a career in Medan for 27 years (1888–1915) and retired to a relaxing life in Germany for the next 27 years.

The Bad Nauheim city archive recorded that, at the age of 51, Kleingrothe retired to Bad Nauheim, a resort town known for its salt springs. He led a contented life, married for the second time, owned several properties, ran a tobacco business and operated a cinema. In 1928, Kleingrothe and his wife departed from Bad Nauheim. As World War II broke out, Kleingrothe and Maria were registered as living in Frankfurt am Main. Kleingrothe passed away on February 25, 1942, in Frankfurt am Main due to influenza, coronary sclerosis, and hardening of the arteries.

Colonial life

Kleingrothe’s photographs depict the development of Medan from a small village into a bustling colonial city, the growth of the tobacco industry, and the diverse communities that lived there, providing a visual record of colonial life. These images depict life, architecture, landscapes, and attire of the time. The growing availability of digital archives has made these photographs more accessible to the general public, and the Indonesian community is captivated by the aesthetic representation of “tempo doeloe”, rekindling an interest in colonial life.

It is essential to acknowledge the selective nature of these photographs, many of which were commissioned by plantation companies, and which served as marketing assets for the companies and the Dutch colonial government. Similar to modern marketing or social media platforms, these photographs were carefully selected to highlight certain aspects while downplaying or excluding others.

While the photographs capture the beauty and development of Medan and the tobacco culture, their power to shape perceptions must be considered. These images predominantly depict the positive aspects or progress of colonisation. The transformation from a dense jungle to meticulously maintained plantations conveys a sense of progress that appears to be possible only through European intervention. By romanticising and idealising colonial life, these photographs inadvertently overlook the exploitation and oppression that occurred behind the scenes.

Similarly, the power dynamics between European overseers and their loyal workers in these images emphasise racial superiority. These photographs promote the advancement of European technology, downplaying the realities the colonised population faced. The photographs depicted indigenous and non-European peoples as primitive stereotypes, reinforcing the idea that they were inferior and needed to be “civilised”. These images supported the idea that the colonisers brought order, civilisation, and progress to “primitive” societies.

Kleingrothe’s captivating photographs, while providing a window into the past, also serve as a reminder of the interplay between visual representation, historical narratives, and the selective shaping of reality.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks the archivist of Bad Nauheim for helping put together the file of C.J. Kleingrothe.

References

Stadarchiv Bad Nauheim 1915-1928.

Sterbebucheintrag des Karl Josef Kleingrothe (1942 / V / 372)

Frankfurter Adressbuch für 1941, 1. Teil, S. 370.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss