A bold development in Prabowo Subianto’s 2024 presidential campaign has been his promise that if he wins, he will invite his vanquished election rivals to join his government. He argues that Indonesia is too big, too diverse, and has too many ethnic groups to reach its potential unless its leaders are willing to work together cohesively. Prabowo’s own post-election-defeat inclusion within President Jokowi’s government in 2019 may thus become one of Indonesia’s defining political precedents.

Jokowi and Prabowo’s eagerness to incorporate their rivals into their governments is indicative of the resurgence of Indonesian integralism.

Indonesian integralism, which David Bourchier argues has its origin in early 20th century Dutch legal anthropology, portrays consensus-based decision-making and benevolent rule as principles that are deeply rooted in Indonesia’s traditional cultural life. Integralist thinkers claim that political contestation, parliamentary opposition, and social struggle are alien and divisive disturbances to Indonesia’s organic modes of communitarian governance. Integralism reached its zenith during Suharto’s New Order regime, which disseminated an ideology portraying the nation as a harmonious family led by Suharto as father.

With the establishment of competitive elections after Suharto’s fall in 1998, Indonesia’s leaders largely ceased to propagate explicitly integralist discourses. However, throughout the 2000s, political parties tended to form governing cartels rather than engage in parliamentary opposition. Beginning in 2014, a series of religiously—and, in the case of the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, ethnically—fraught elections seemed to signify the emergence of more substantial political contestation and a potential curtailing of cartelisation tendencies.

Jokowi and Prabowo’s 2019 rapprochement ended this period of polarisation, and Jokowi subsequently built a massive governing cartel. Nonetheless, in 2019, it still seemed that cartelisation would remain a primarily post-election phenomenon motivated by rent-seeking. But Prabowo’s pre-2024 election promise to include all parties in his government is a move beyond pragmatic rent-seeking politics; it is an attempt to reinstall integralism as Indonesia’s explicit guiding ideology.

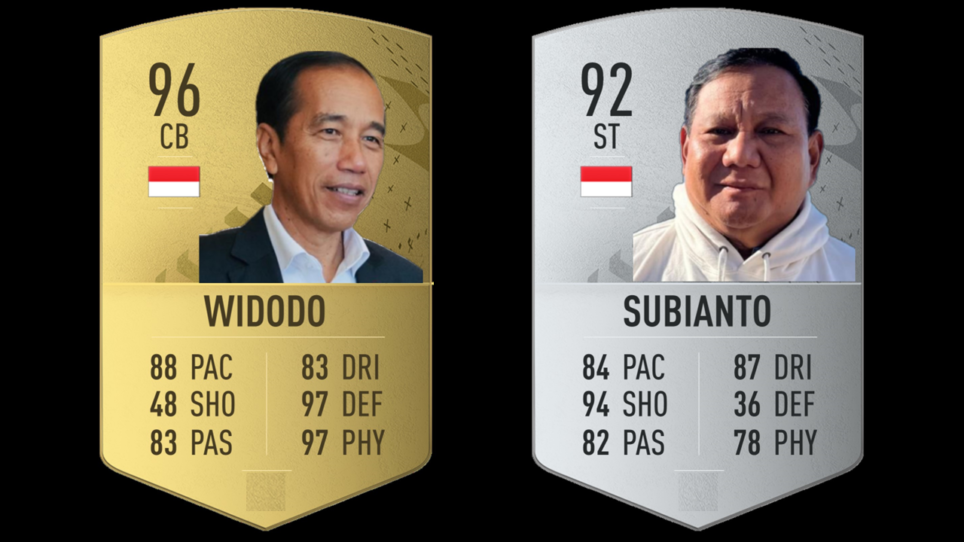

In justifying his promise, Prabowo is deploying a new analogy in place of his former father-in-law’s “family” discourse: football. If Indonesia is to succeed, he explained in an interview with Najwa Shihab aired on 30 June, it must be like a champion football team.

We can win if the starting XI works together. In fact, not just the starting XI, but also the substitutes, coaching staff, the manager, water carriers, and massage therapists. One team… Indonesia needs to work together in this way.

He made similar comments in a speech at the Indonesian National Police Education and Training Institute on 16 June, declaring: “Jokowi is the captain of our starting XI, and I am the striker!”

Prabowo’s football analogy would seem to invite unpalatable comparisons. Indonesian football has long been rife with hooliganism and match-fixing, and the first anniversary of the legally controversial Kanjuruhan Stadium crush looms. Moreover, likening politics to football raises the question: wouldn’t the governing coalition within the DPR function best when faced with a robust opposition, just as a strong football side rises to the challenge when playing a worthy opponent?

The political prospects of Jokowi’s sons

Central Java offers a good base for a Widodo dynasty, but tensions with PDI-P are a hurdle.

Indeed, when we turn our attention to Erick Thohir, the recently elected chairman of Indonesia’s national football association, it starts to seem as if Prabowo’s football analogy might be more literal than it first appears. Thohir managed Jokowi’s 2019 presidential campaign, has served as Minister of State Owned Enterprises since 2019, and is likely to run as vice president in 2024. His brother, Garibaldi Thohir, is President Director and major shareholder of energy giant Adaro.

Erick Thohir owns English League One’s Oxford United F.C. with Anindya Bakrie, President Director of the Bakrie & Brothers conglomerate and son of former Golkar Party chairman Aburizal Bakrie. Thohir also owns Indonesian Liga 1’s Persis Solo with Kaesang Pangarep, Jokowi’s younger son. Thus, at the heart of Indonesia’s network of elites, joint ownership of football clubs tie three of Indonesia’s most powerful families together. Jokowi may be the captain of Oligarchs United F.C., but Thohir is surely the club’s manager.

So, football is increasingly serving as the discursive and material glue that holds Indonesia’s pivotal alliances together and that fills in the cracks which might otherwise broaden into genuine political contestation. If Indonesia is once again becoming an integralist state, this time it is a football state just as much as a family state.

All of this helps explain why former frontrunner Ganjar Pranowo’s decision to prioritise Palestine over football in the Under-20 World Cup fiasco backfired so decisively. Prabowo will make no such errors. His soon-to-be-completed football academy facility in West Java—which he has already offered to Liga 1’s Jakarta Persija as a free training ground—and the Under-17 World Cup that Indonesia will host in November give him ample opportunity to run a football-fuelled election campaign. The striker is well positioned to finally claim the title he has long coveted.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss