Within Thailand’s overwhelmingly Buddhist population, the Dhammakaya version of Buddhism has amassed a huge following but also created enormous controversy, Khemthong Tonsakulrungruang writes.

Thailand’s Department of Special Investigation (DSI) recently announced that it would soon arrest the abbot of Dhammakaya Temple, Phra Dhammachayo. The arrest will cause another big drama in what has been a long series of attacks on this controversial Buddhist group.

The case began with the DSI wanting to interrogate Dhammachayo as part of a fraud investigation relating to temple donations. The abbot refused to appear, arguing, quite rightly, that the case was politically motivated so justice might not be forthcoming. The DSI’s previous raid failed to reach the abbot because thousands of Dhammakaya followers formed a human shield. This time, the DSI boasted it had a secret plan. The Dhammakaya responded pre-emptively by raising the temple walls and mustering its followers to form another human shield.

The siege being waged against the Dhammakaya version of Buddhism is instructive. The dispute reveals a problematic relationship between Thai political authorities and Buddhism.

The 1980s saw the waning of the importance of the Sangha Council, the central body governing Thai Buddhist orders. It no longer supplemented rulers with traditional religious legitimacy. Thailand was then joining the wave of globalisation. The communist threat subsided and the volume of trade soared. Politicians could claim a more materialistic legitimacy through economic growth and development. Withering government attention to the Sangha Council, as well as a series of high-profile scandals concerning famous monks, opened up the field for non-mainstream Buddhist groups to increase their prominence. Some groups became anti-materialistic and anti-globalisation, such as Santi Asoka, which dreamed of returning to a pure form of Buddhism. At the other end of the spectrum was the Dhammakaya group, which chose to capitalise on the wave of capitalism.

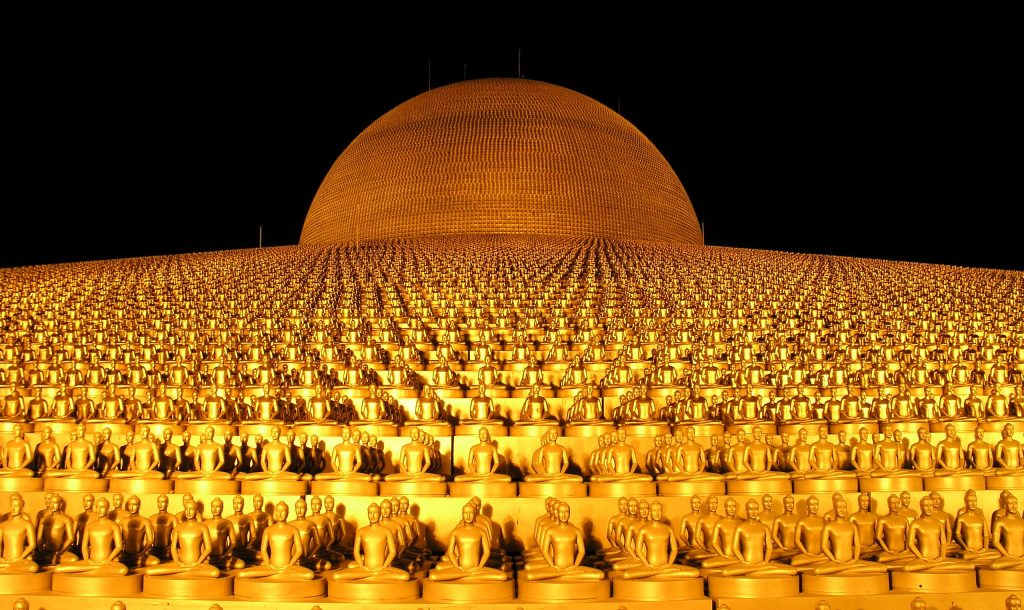

Dhammakaya succeeded for two reasons. First, its teaching was simple and easy to understand. “Bun” (merit) could be quantified in monetary terms. The more donations one makes, the more merit one shall gain. Second, its use of new visual technology, including light and sound effects, helped lure people in. It wasn’t long before Dhammakaya began to grow. Its followers numbered in the tens of thousands, encompassing business people, academics, and politicians.

Many Thais viewed the emergence of Dhammakaya with scepticism or even disdain. For them, Dhammakaya’s teaching was too different from the conventional one. To build the modern state of Thailand, King Rama V centralised Buddhism in the kingdom in 1902. There was only one official version of Buddhism, which, together with the nation and the King, founded the Thai identity. Other strains of Buddhism, mostly regional, were heavily suppressed. Dhammakaya’s unconventional, materialistic interpretation of Buddha’s teaching sounded unfamiliar, un-Buddhist, and eventually, un-Thai. In addition, its immense wealth was unacceptable for Thais whose concept of Buddhism was otherworldly and self-sufficient.

Despite criticism and prosecution, the Dhammakaya strain of Buddhism survived and thrived. It did this firstly, by not trying to challenge the authority of the Sangha Council outright, something Santi Asoka had done leading to an order to defrock its leader, Bodhiraksa. Instead, Dhammakaya supporters fostered good relationships with several senior abbots. Second, Somdet Phra Nyanasamvara, Thailand’s Supreme Patriarch at the time, was incapable of dealing with issues. His frail health prevented him from taking any decisive action. The Sangha Council did not implement his 1999 order to defrock Dhammachayo. Moreover, the Dhammakaya group was politically well-connected. Political intervention ended the attempt to prosecute Dhammachayo.

However, this uneasy truce ended with the death of the Supreme Patriarch in 2013, unleashing a nightmare which had long been feared by many. According to Sangha law, the most senior member of the Sangha Council shall become the new Supreme Patriarch. The rule is clear and rigid, leaving no room for alternatives, yet infighting over who shall be the successor continues. The only candidate, Somdet Phra Maha Ratchamangalcharn, is known for his support of Dhammachayo. His ascension to the position of Patriarch means Dhammakaya Buddhism would control the Sangha Council more effectively.

Furthermore, an ardent supporter of Dhammakaya is the Shinawatra family. Thaksin’s opponents thus consider Dhammakaya Buddhism their enemy too. The ambition of Dhammakaya followers to dominate the Sangha Council is likened to Thaksin’s domination of Thai politics.

Thailand has struggled both economically and politically in the past decade, politicians are returning to a reliance on religious legitimacy. The legitimacy deficit is more acute in the current regime, whose military government receives little popular support.

As a result, the Dhammakaya version of Buddhism is considered “Mara” – the demon the government has to get rid of to qualify as a good ruler. Dhammachayo is being charged with fraud while Somdet is being investigated for allegedly illegally importing vintage cars. But dismantling Dhammakaya would not be an easy task. Although the National Council of Peace and Order is keen to do this, Dhammakaya has amassed a very large number of supporters, both laypeople and monks. Heavy resistance is anticipated.

While the fraud allegations deserve a serious and professional investigation, arresting Dhammachayo would not solve the problem of the Thai Sangha Council. Reform of the Council is long overdue. But any reform must come from within, and government intervention would unnecessarily complicate the matter. The Sangha law is obsolete. Promotion is based solely on seniority. The Sangha Council has absolute power over all monastic matters. There is no check-and-balance to guarantee transparency of its decision-making. Members of the Sangha Council are weak and corrupt. Normal Buddhist temples are no less scandalous than Dhammakaya ones when it comes to sex, money, wildlife trafficking and forest encroachment, to name but a few of the issues. One of the most outspoken advocates for the destruction of the Dhammakaya movement is Phra Suwit, known as Buddha Issara, who participated in the Bangkok Shutdown campaign in 2013-2014. His men blocked the road, assailed innocent people, and extorted money from alleged Thaksin supporters. Obviously, Phra Suwit is not in a position to restore faith in the Thai Sangha.

Most importantly, Thais must realise that there can be more than one version of Buddhism. Dhammakaya should be free to interpret and teach whatever it considers right. It should be subject to debate and criticism, but not harassment from the government.

Anti-Dhammakaya sentiment in Thailand is very strong. The 2016 Constitution demands that the government provide support for the Theravada branch of Buddhism. This specificity of language may surprise many readers. What exactly is the definition of Theravada Buddhism? How could the government identify Theravada and non-Theravada? There is much speculation that this clause was written in order to target Dhammakaya, but as the draft was prepared in secrecy, there is no way the public can verify that allegation.

If true, however, the National Council of Peace and Order has gone to great lengths to get rid of one Buddhist group at the cost of raising religious tensions in a country that has already witnessed years of Muslim insurgency. It is a great price to keep the purity of Thai Buddhism.

Khemthong Tonsakulrungruang is a Thai constitutional law scholar.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss