Since the National League for Democracy’s landslide November 2015 election victory, discussions of Myanmar’s political future have taken an interesting turn. The NLD—ruling in coalition with military and ethnic political interests—needs to maintain a delicate balance. It cannot afford to alienate the millions of voters who showed it such exuberant support. In practice, this means certain issues are deemed too hot for strong policy action. At the top of that list is the Rohingya conundrum: a political stalemate that has morphed into a catastrophic humanitarian crisis. The NLD is not prepared to risk its support from among Buddhist voters who resent any suggestion that the Rohingya, or other Muslims, deserve equal treatment from state authorities. The military also appears to have determined that any shift in NLD discussion of the topic threatens the red lines around its continued partnership with the elected government.

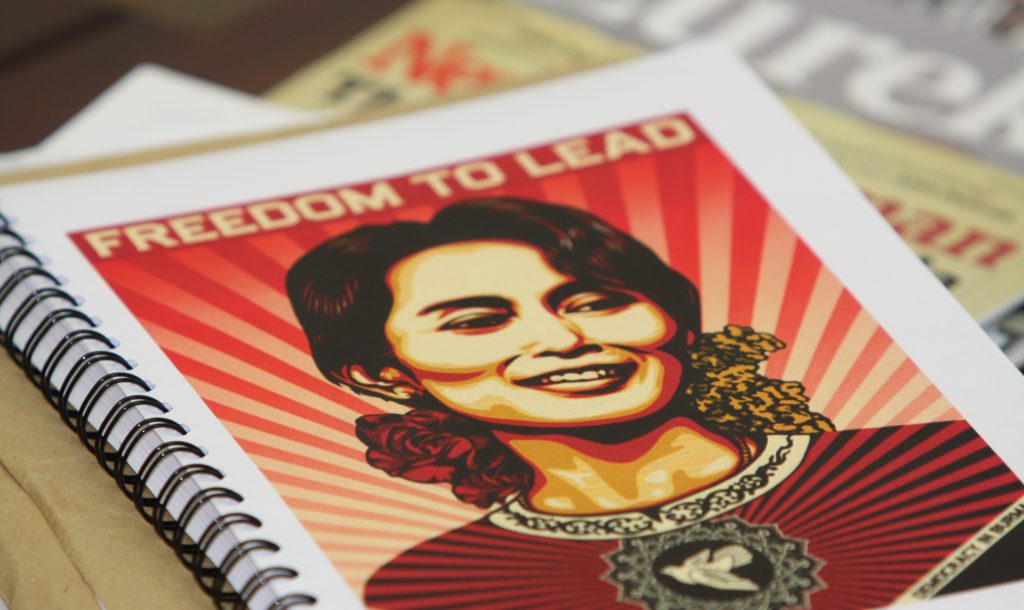

For a long time, it was possible for activists from around the world, and from inside Myanmar, to project their personal expectations onto a hypothetical NLD government. Aung San Suu Kyi was a convenient symbol of peaceful resistance to military rule. Unsullied by the pragmatics of day to day decision making, her supporters, from near and far, rejoiced in her defiant purity: her Nobel Peace Prize; her years of imprisonment; her sacrifice of self and family; her steely and dignified resolve. The world fell in love with the idea that she could lead a democratic and inclusive country, where justice would prevail, and where a popular mandate would right history’s wrongs.

Unfortunately, in this model, wishful thinking often substitutes for careful analysis of the challenges confronting every Myanmar government, as well as the specific limitations encountered by the NLD. Their coalition with the military is the engine for an evolving compromise about the distribution of power in the country, with the 2008 constitution setting the terms of the army’s continuing dominance of those areas where it perceives its core interests at stake. Nobody in a position of real power, least of all Aung San Suu Kyi, has made any serious move to question the basis of this arrangement. Where the NLD previously proposed constitutional amendments, the focus remained on clearing obstacles to Aung San Suu Kyi’s personal ambitions, rather than to deleting the military’s controlling stake. The footwork required to allow Aung San Suu Kyi’s elevation to the new role of State Counsellor goes to show that the military has few serious concerns about her capacity to challenge their mandate. In fact, they have Aung San Suu Kyi exactly where they want her.

For supporters of human rights, the rule of law, and participatory democracy, this outcome is far from ideal. It is no surprise that on her May 2017 visit to Europe, Aung San Suu Kyi was met by protestors crying “shame”. The impunity of the armed forces has not diminished, nor has there been a significant expansion of rights under the NLD. In some respects, Myanmar was a freer place in the final years of the former Union Solidarity and Development Party. The former military rulers were confident in their abilities and relatively comfortable letting the public make up their minds. The most obvious outcome of this approach was the election victory of the NLD in 2015. That would not have happened had the successors to the old military regime decided that it was out-of-bounds.

There is no purity in what has followed, and the NLD has proved an unsteady ally to the activists that made its 2015 victory possible. Instead the NLD has needed to compromise with its backers in uniform. What this means is that Aung San Suu Kyi has yet to make any serious move to attack the vestiges of military power and there are indications that she will remain reluctant to do so. Where does this leave the activists, in Myanmar and abroad, who fought so hard, for so long, for a more genuinely democratic system? Many of the big international organisations, such as Human Rights Watch and Global Witness, now end up protesting against Aung San Suu Kyi and her NLD-led government. They find it impossible to reconcile the values and ethics of resistance to the military regime with the pale facsimile they perceive has now been endorsed by the top NLD leaders. Other foreign activists point to ethnic politics, gender inclusion, religious conflict and economic disparity as areas where the NLD has either not done enough or has, in fact, exacerbated longstanding problems.

Squandering the support of liberal minded folks from outside Myanmar is not yet an issue for the NLD. They now weather plenty of criticism from academics and NGO analysts, but that is on par with every other country in Southeast Asia, even the genuinely democratic ones. Indeed, the greater the level of democracy and openness (thinking here of Indonesia and the Philippines, but even Thailand before the 2014 coups) the greater attention received by difficult social and political issues. Laos and Vietnam, while the most authoritarian societies in Southeast Asia, tend to receive only occasional criticism. Brunei, as an absolute monarchy, is probably even more neglected. In those cases, there is no expectation of a plurality of ideas. And even the soft authoritarian systems, such as Cambodia, Singapore and Malaysia, tend to have found equilibrium with international expectations of their illiberal values.

By contrast, there is still a general suggestion that Myanmar should be better and that the election of the NLD in 2015 will help build momentum towards a more democratic future. When the current government fails to live up to expectations, people feel comfortable voicing their disappointment, even anger, at the missed opportunity. For now, the lightning rod issue of the Rohingya draws consistent international condemnation. Ethnic conflicts come a close second on the list of the big problems that the NLD government was expected to handle better.

Pragmatists inside Myanmar still point to the potential for further improvement and for the creation of a robust democratic culture that spills beyond the constraints of the NLD. Senior figures in the party appear reluctant to take serious risks, a situation that will eventually embolden the young guns that feel disempowered by its hierarchical and conservative management. When preparations for the 2020 election get more serious, these groups will start to consider how they can reshape Myanmar politics to more fully account for the aspirations embodied by the democratic struggle.

They are not short of ideas but currently find it hard to get heard within the NLD’s structure, where Aung San Suu Kyi is a towering presence. Getting out of her shadow will be the name of the game for local activists, but also for their foreign supporters. The fact that Aung San Suu Kyi is so reluctant to answer media queries, or engage with the public in an unscripted fashion, ensures that her message gets diluted quickly. But she does not seem to care. The risk is that as her message fades, so does her moral and political authority.

……………

This post originally appeared as part of the T.note series of analysis papers published by the Torino World Affairs Institute (TWAI), and is reposted with permission.

Nicholas Farrelly is a co-founder of New Mandala and Associate Dean of the Australian National University’s College of Asia and the Pacific, where he also leads the ANU Myanmar Research Centre.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss