Though the head-to-head nature of Indonesia’s July 9 presidential election made for a polarizing political environment and some over-the-top rhetoric, it also offered an interesting peek inside campaign finance strategies.

As has been the case for years, these reports must be viewed with a high degree of skepticism, as in all likelihood they are incomplete and far from an exhaustive account of every penny handled by either campaign team. Though the reports are required by law, few challenges if ever have been filed over fundraising-related issues, rendering compliance with the regulation essentially voluntary. Furthermore, campaign finance rules do not pertain to unaffiliated third-parties, i.e. political action committees (PACs of American infamy), so that thanks to the legal loophole, these groups are permitted to operate freely

However, despite all their limitations, the candidates’ fundraising statements are instructive as a measure of what candidates feel obligated to declare. The reports submitted by this year’s presidential contenders reveal stark differences in approaches and sources of support that are nearly as divergent as the candidates themselves. They also reveal fundamental weaknesses in financial management and the underdeveloped nature of strategic fundraising in Indonesian politics.

Let’s talk turkey

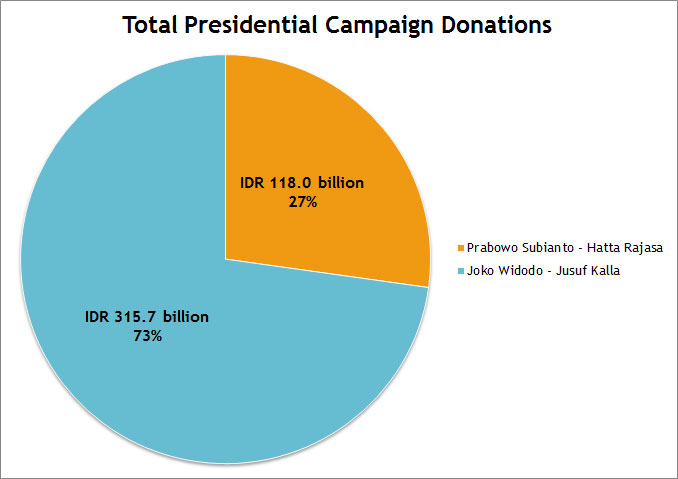

Looking at total reported donations (operative word reported), there are two possible conclusions to be drawn. Either the reports are to be taken at face value, and Jokowi dominated Prabowo by raising more than two-and-a-half times the amount of his opponent, or Prabowo’s reported donation total of IDR 118 billion is woefully short of the full resources at his disposal.

Power to the people?

One of the most drastic differences between the two candidates is their respective bases of financial support. Between May 31 and July 4, the Joko Widodo-Jusuf Kalla camp reported donations from more than 40,000 individual donors, with the vast majority (89%) of donations in denominations below Rp 1 million (US$100). This “Obama-style” fundraising campaign, to collect small donations from a broad swath of everyday citizens, is a novel concept in national-level Indonesian politics and one that has struggled to gain popularity….until now. Jokowi reported receiving IDR 37.5 billion from the public. Supporters welcomed the idea, with an apparent willingness to invest their hard-earned money in making Jokowi’s vision a reality.

In contrast, Prabowo’s financial support base consisted of a mere 48 individuals. His campaign targeted rural demographics with messaging about plans to tackle poverty and promote prosperity, but it relied on wealthy individuals to make this vision a reality. Drawn primarily from Jakarta’s upper-class, these deep-pocketed donors ponied up an average of more than IDR 45 million.

Conspicuously absent from Prabowo’s list of individuals was his brother, Hashim Djojohadikusumo, whom Forbes ranked as Indonesia’s 42nd richest as of November 2013. Hashim’s presence was noted, by extension at least, in Prabowo’s corporate donors list. Cursory research reveals Hashim or his children control five of 12 corporate donors, which each maxed out the corporate donation limit at 5 billion each. Also absent from Prabowo’s roster of supporters was billionaire media mogul Harry Tanoesoedibdjo.

Interestingly, the Prabowo camp made a point of attacking Jokowi for “begging for money in the street” early in the race, until ultimately recognizing the power of public donations and adopting the strategy in an abrupt about-face on 13 June.

Cash flow

In addition to having developed a broader base of support, the Jokowi camp also reported raising more than twice the amount of cash as Prabowo in the same period. In a land where cash is king, it may have proven to be a deciding factor in this race. Or, as the gaps in his donor list suggest, Prabowo simply did not feel a need to report everything he received.

Note: Prabowo came up short in every category of fundraising comparison against his rival Jokowi. Although he was able to gather a small band of deep-pocketed donors, it wasn’t enough to top Jokowi’s IDR 315 billion fundraising effort, at least according to official documents. Jokowi-JK’s first period campaign finance report listed a total of IDR 44,507,420,305 in donations. However, in the camp’s second period report, it revised the first period figure for unclear reasons down to IDR 23,892,548,897. When combined with IDR 271,151,437,701 in new donations listed in the detailed second period report, the total raised over the campaign period comes to IDR 315.6 billion.

As seen on TV – the power of advertising

The “services in kind” category of Indonesian campaign finance reports is a black box, with services vaguely described (if at all). The process by which a value is determined for said services is even more opaque . However, the Jokowi camp clearly benefitted from the support of media mogul Surya Paloh’s NasDem party, which contributed some IDR 152 billion for “advertising costs”. Prabowo’s own Gerindra party only put up a fraction of that amount at IDR 43 billion for advertising.

Research conducted by media monitoring group Satu Dunia on media spending in five cities (Jakarta, Medan, Banjarmasin, Makassar and Surabaya) showed that each candidate had spent roughly IDR 60 billion on a combination of television, print and radio advertising. With this in mind, it seems unlikely that if Prabowo only raised a total of IDR 118 billion, he would spend half (52 percent) on media coverage in just five cities. Jokowi’s expenditure from this limited media monitoring exercise comes to a much more modest 19 percent, suggesting that his reports come closer to full disclosure.

Dude, where’s my party?

Though both candidates reported similar amounts of support from the business community and claimed to have dipped into their own pockets to a nearly identical degree, a drastic divergence emerges when comparing the donations from political parties. Prabowo was able to call upon his own Gerindra party for a total of IDR 53.3 billion, and although he was nominated by a broad coalition, Gerindra was the only one to put money into the race (at least on paper). This may be a dramatic underrepresentation of real donations, however, as the financial links to Golkar are missing from the report.

While Jokowi raised a whopping IDR 229 billion from his coalition partners (NasDem – IDR 158 billion; PKB – 37.5 billion; PKPI – 2.5 billion), his own Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) contributed a meager IDR 27.5 billion.

Mismanagement creates missed opportunities

Looking at the detailed reports from both campaigns, it is clear that neither side employed a sophisticated system to manage donor information or maintain relationships after the race is over. During the first reporting period, Jokowi’s team reported Rp 2 billion in donations from donors who had yet to be identified – suggesting that the public response to this fundraising model overwhelmed organizers’ ability to keep up. His team was unable to rectify that situation in the weeks that followed, with many “donors” listed as “ATM transaction” or “Cash Transfer” and donations in odd amounts, such as IDR 1. Reporting from the Jokowi camp also suffered from basic inconsistencies from one report to the next. His first period report totaled IDR 44 billion in donations, but the second report, submitted weeks later, referred back to the previous sum as IDR 23 billion. Even within the second period report, a discrepancy of IRD 100 million appears between the summary page and 1,008 pages of detailed line-items.

For the time being, the general public can take comfort in knowing that they are unlikely to receive the automated fundraising solicitations commonly found in many Western democracies as election season heats up, but the fact that neither campaign seemed to make a conscious effort to keep in touch with key supporters after the dust settles is disheartening. To squander this momentary public enthusiasm for politics rather than turning it into a lasting, issue-based constituent communications network is a sad outcome indeed.

Candid candidates and public perception

As I noted at the outset of this piece, the largely voluntary nature of these reports limits their use as a forensic tool for serious research into the inner workings of campaign finance operations. When final expenditure reports are filed on July 20, the candidates simply have to ensure that they do not exceed the reported amount of donations to stay on the right side of the law, and if history is any indication, no one is likely to object.

What we can glean from these reports, however, is a drastically different picture of candidates’ perceived need for transparency. It is not necessarily true that Jokowi raised two-and-a-half times the amount of funding as Probowo did, but the data would seem to indicate that Jokowi felt compelled to be comparatively open about how much support he received, and from whom. Doing so would certainly bolster his image of being a man of the people. Prabowo’s reports, on the other hand, indicate a lower level of credibility, and as a corollary, a lower level of accountability to public scrutiny.

…………………

Justin Snyder works with a variety of organizations on democratic governance and development issues in Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss