In July, authorities in Myanmar suspended Popular Journal for a week after it repeatedly published racy pictures of models, like these two, on its centre spread:

Although these sorts of photos are increasingly commonplace in the country’s burgeoning private print media, which is rushing to catch up with its counterparts elsewhere in the region, officials still appear to take umbrage when a real or imagined line is crossed. Popular seems to have learned its lesson and since resuming publishing has–for the time being at least–reserved its pages for more fully clad ladies.

While Popular was off the stands, Living Color ran a feature article on youth styles and “traditional” culture. The writers provide data from a couple of loose surveys on youngsters’ attitudes towards old and new-style clothes, and give a considered assessment of local trends towards the types of clothing that teens in nearby Bangkok have worn for years. The editors have peppered the article with photographs of young women baring their knees and thighs on street corners, at festivals and in beauty shows, making quite clear that the fashion fuss is much less about spiky haired boys than it is about skimpily dressed girls.

Is the appearance of Burmese women’s legs in the media and other public spaces a genuinely new or shocking phenomenon for people in Myanmar? Are these the legs of change? Or are they multiplying visually but signifying nothing?

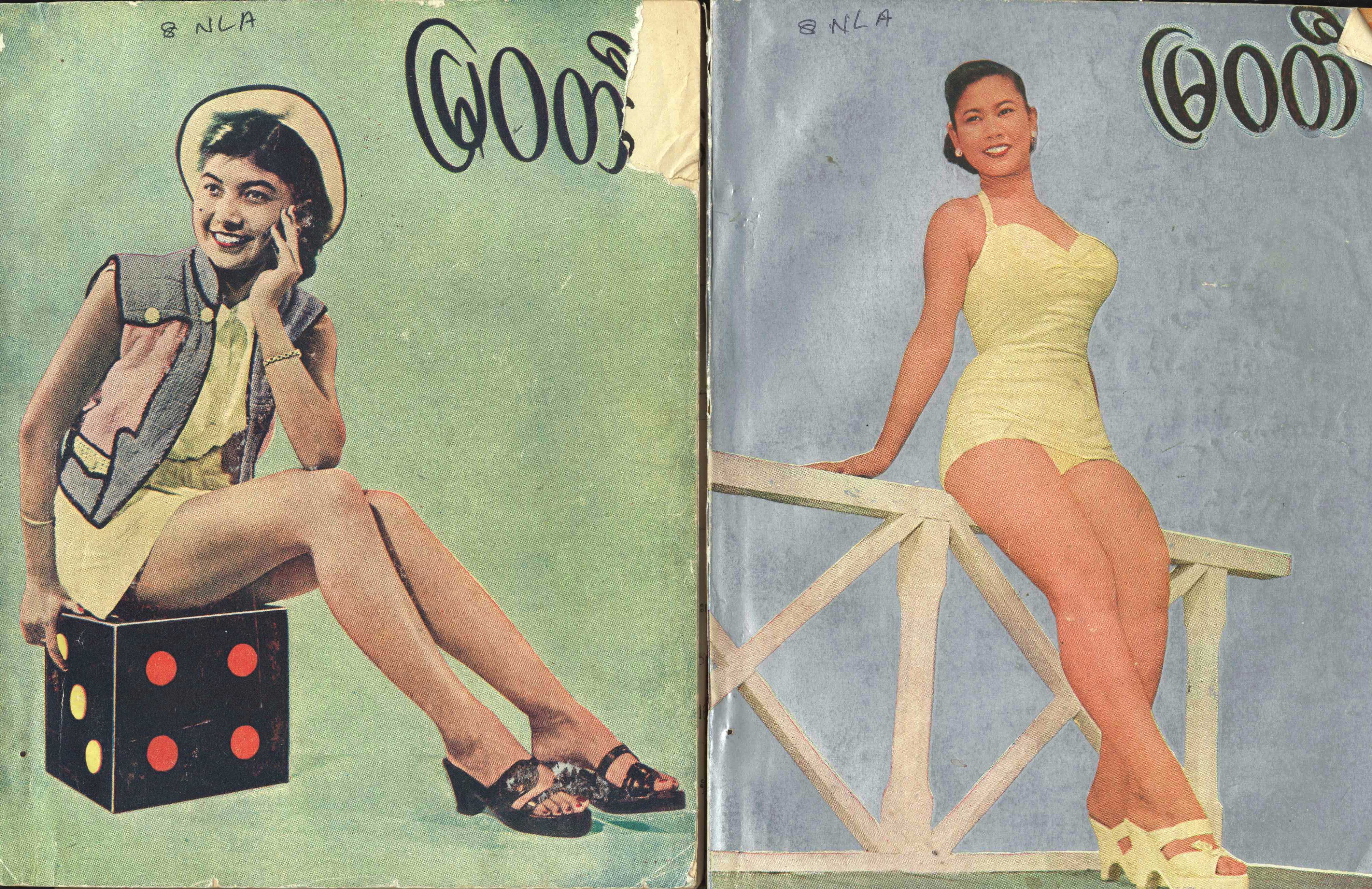

To put recent trends in perspective, the National Library of Australia has a collection of serials that goes back to the 1950s, including the long running Myawadi magazine, which–since Popular was not around then–can be used as a barometer of sorts. Let’s start with a couple of covers from 1958:

If Burmese women’s legs were fully exposed and in print over a half a century ago, a decade later they were not. By the mid-1960s, the sexualized portrayal of women was out. They were the fabric of a new socialist economy, as was the fabric on their bodies. Models were still attractive, but their hair was cut short or tied back, their outfits no-nonsense. There was work to be done. On the cover of Myawadi, peasant women wield their sickles energetically, while students get the better of chemistry:

Into the 1980s, and the socialist iconography had worn thin. Female models are by this time much less businesslike. They lounge around, casting vague feminine airs, wearing digital watches and sporting disco hairstyles, but their clothing is still conservative; hemlines rarely get past the ankle, if they appear at all:

By the turn of the century, new publishers were pushing stodgy monthlies into the corners of the newsstands, replacing them with cheaper and flashier weeklies. Myawadi has soldiered on, and after a period of jeans and singlets, its editors have reinvented the magazine on the side of “tradition”, with covers like these consciously rejecting the mini skirt in favour of a constrained, authorized female archetype:

Anthropologist Monique Skidmore has written (in Women & the Contested State, Skidmore & Lawrence, eds.) that in Myanmar “there is a certain kind of regulation and control of women’s bodies mandated by the state in an attempt to satisfy [the] perennial quandary for male dictators” about how to manage women’s subversive power while also shoring up the masculine state’s defences. Yet the billboard queens flirting with modernity that she wrote about only a few years ago already seem chaste when compared to the new generation of centre-spread princesses. The women of pulp journalism and Korean television, not those prim refined types on the cover of Myawadi, are the rage. Htet Htet Moe Oo, yesterday risqué, is today passé. Hip hop culture now holds sway. As for what’s next, who can say?

[This post is provided by the National Library of Australia as part of our Book Zone feature. For further information on the featured publications contact Nick Cheesman at ncheesman@nla.gov.au] Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss