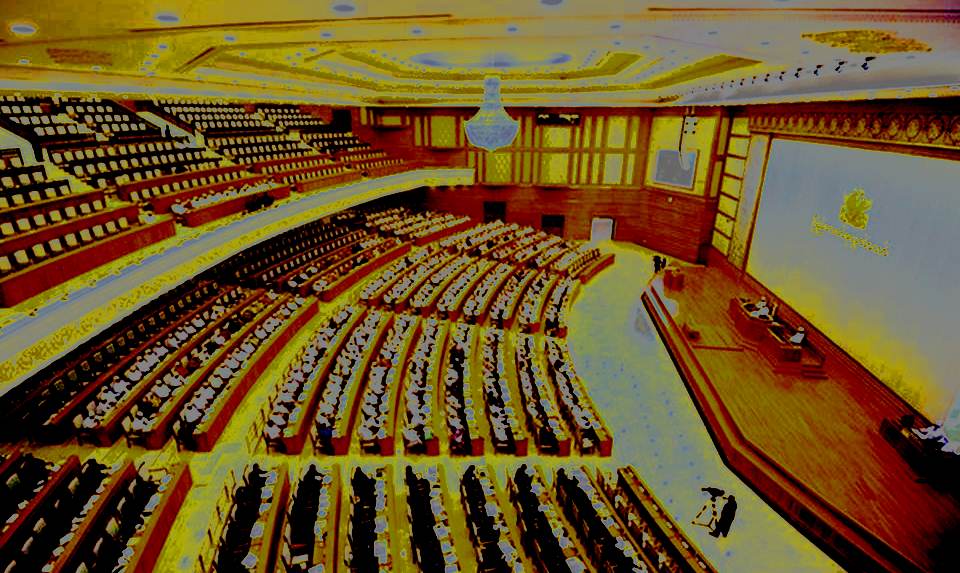

As legislators filed into Myanmar’s national parliaments yesterday for the first sitting since power was handed over to the new government in March, they were joined by a relative novelty: local reporters from privately run foreign and domestic media organisations.

Barred from entering the hluttaw compounds during the first sessions, which were convened on 31 January following the November 2010 election and ended 30 March, journalists were instead forced to rely on state media transcripts and after-hours interviews with mostly opposition politicians.

Announced at a press conference on 12 August, the decision to allow journalists into the parliaments was a surprise concession by the new government. The State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) was notoriously media shy, perhaps with the exception of the now-disbanded Military Intelligence. Official press conferences, when they occurred, were often scripted affairs, with journalists told the questions they had to ask. Those who spoke out of line risked losing their jobs. The present Minister for Information, U Kyaw Hsan, a noted conservative and trusted ally of former Senior General Than Shwe, was one of the few SPDC ministers to keep the same ministerial post in the transition.

This announcement was overshadowed by discussion of hostilities in Kachin State, economic issues and, most remarkably, U Kyaw Hsan breaking down in tears while apparently talking about the challenges faced by the new government.

The significance of allowing journalists into the parliament, however, shouldn’t be underestimated. (Incidentally, just a few days earlier a diplomat had asked me whether I thought it would be possible, and I had replied, “No chance.”)

It represents another attempt by U Thein Sein’s nominally civilian government to break with the SPDC era, in a similar vein to the anti-corruption and poverty alleviation discussions, the removal of propaganda slogans from the state media and last week’s meeting between the president and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

It’s not clear what journalists will be able to do, of course: entering the chamber is illegal and onsite interviews with representatives are apparently out of the question. U Kyaw Hsan warned that “the journalists also need to show self-discipline [in parliament]” and refrain from asking aggressive questions, and domestic publications are still under government censorship.

More likely, they’ll be able to watch proceeding on CCTV elsewhere on the site. This may not seem like much of a concession but having independent observers inside the parliament is a much-needed step towards building trust in the new political system, and is also likely to lead to improved media coverage of the sessions.

It’s an indication that this sitting of parliament is taking place at a critical time for the new government, which many observers believe has been wracked by an internal struggle between progressive and conservative elements, led by President U Thein Sein and Vice President 1 Thiha Thura U Tin Aung Myint Oo respectively.

The president’s dominance of the state and domestic media in recent weeks could be interpreted as his gaining the ascendancy, and the unprecedented image of U Thein Sein and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi under a photograph of Bogyoke Aung San in state media on August 20 – along with her conciliatory comments, which were published in private domestic publications – will likely have strengthened his hand.

But in the background, the Kachin conflict rumbles on and tensions with several other armed groups remains high, with no long-term solution in sight. The economy continues to struggle with the appreciation of the kyat, which has crippled exports, few political prisoners have been released and corruption does not appear to have declined.

The new government has been criticised for making a lot of positive noises but doing little in the way of decisive action. It desperately needs domestic credibility, and it knows this will only come by making much-needed progress on economic and social issues that affect a large number of people.

My belief is that the early signs are actually more promising than is widely realised, even if I’m probably not quite as optimistic as one unnamed expert quoted by news agency AFP over the weekend.

“We should be very careful in imagining that the reform of a country like Burma will happen overnight but it is moving in the right direction faster than one could have imagined,” the expert said.

The nature of the reconciliation issue means it will not be achieved through parliamentary process, particularly given neither the armed ethnic groups nor the National League for Democracy are represented directly. Yet there are high hopes that other pressing matters will be addressed in parliament.

At the August 12 press conference, U Kyaw Hsan flagged a number of impending changes, including updating tax and foreign investment laws, amending a 1907 law that facilitates forced labour, and introducing legislation to legalise microfinance programs. (The full pdf version of the following day’s New Light of Myanmar is available here.)

There are also a number of draft laws that were submitted to the attorney general’s office for promulgation during the SPDC era, in some cases more than a decade ago. These cover areas such as intellectual property, environment and labour and could potentially be tabled in parliament for approval. Bill Committees formed in March have apparently been hard at work, examining existing laws and getting advice from legal and other experts in order to prepare reports for submission to parliament.

Representatives have submitted literally hundreds of questions and proposals for approval ahead of these sessions, as well as a number of bills. While opposition parliamentarians dominated the question-and-answer sessions in February and March, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) and National Unity Party will likely play a larger role this time.

What should we expect from this? Questions should be better formulated and discussions more robust, at a minimum. Responses should be more relevant because it will be the new government ministers, rather than those from the SPDC, doing the talking. (For some background on the first sessions, I offer this earlier piece.) The Myanmar Times report quoted a member of the Bill Committee as saying it expects “more than 10” laws to be adopted by parliament.

Of course, it’s difficult to predict exactly what will happen. The sessions might last a week or two and only focus on procedural issues, like the upcoming by-elections. Yet I think that’s unlikely, because it would be neither in the interests of the government nor the majority of parliamentarians.

While the executive and legislature are separate – government ministers are by law required to resign as members of parliament and give up senior party posts – they are widely seen as one and the same for several reasons. The majority of people have no access to or no interest in reading the much-criticised 2008 constitution, for a start. Perhaps more significantly, most members of the government were originally SPDC ministers and for a brief time USDP representatives in parliament following the election, before resigning these posts to join the new government.

USDP representatives will no doubt be aware that their electoral fate is in the hands of constituents, regardless of the extent to which this group can be cajoled or threatened. All members of parliament will face re-election in a little over four years, which is a long time in an uncertain political climate, and will want to consolidate their positions. However remote, they’ll be considering the possibility that the National League for Democracy will re-register before 2015, or even this year’s by-elections.

Similarly, the government needs to allow the national parliament to strengthen as a democratic institution in order to generate some legitimacy, particularly within the country. (Those who vote need to see some progress. After all, representatives are not elected by the Western media or exiled activists.)

The interests of the government and parliament will not be perfectly aligned, however. Unlike the government, a large proportion of USDP representatives – probably more than half – are not former military personnel. In many cases, including Vice President 2 Dr Sai Mauk Kham – an ethnic Shan doctor from Lashio – they come from the professional classes, which would know all too well the problems the country is facing.

If a 40-member government can’t maintain unity, it’s unlikely the 350-plus USDP representatives in the upper and lower houses will vote along party lines each time, particularly given their diverse backgrounds. Indeed, some people I’ve spoken to say they are expecting the USDP to split in coming years – hardly a first in the fractious history of Myanmar politics. I’m sure many like me will be watching closely for evidence of internal divisions.

Not surprisingly though, the majority of people remain disengaged from Myanmar’s new discipline-flouring democracy. Both the expectation and criticism that were apparent in January when parliament sat for the first time are noticeably absent this time around. The excitement (for some) of voting for the first time in 20 years has dissipated. But while these sessions will be less historic than the first, they are likely to give us a better indication of the direction we can expect the country to take over the next four years.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss