As one gets older, memories of past times and old friends tend to fade, but they also become more important as milestones along (to resort to cliché) life’s busy highway. An inventory of my modest art collection recently brought this home to me, as it prompted recollections of my early days in Burma (as Myanmar was then known).

I was posted to the Australian embassy in Rangoon (now Yangon) as Third Secretary in January 1974. I lived in Burma for two and a half years, leaving in August 1976. I did not fully appreciate it at the time, but I was there during a period of considerable movement in the local art scene, which I first stumbled across by accident, but later came to embrace.

The main reason for my developing interest in this subject was my friendship with Sun Myint and his two sisters, Tin Tin Sann and Khin Myint Myint. All three were very talented artists, who together had a major and lasting impact on the local art scene. I also became good friends with another noted Burmese artist (and author), Ma Thanegi.

Not long after my arrival in Rangoon, I was invited to dinner by the diplomat I was due to replace. He wanted to give me an opportunity to inspect the bungalow on Monkey Point Road (now Thanhlyet Soon Road) where I was to live during my posting. It had originally been built for the manager of the oxygen gas factory nearby, and consisted of two bedrooms and a kitchen/laundry surrounding a large open plan living/dining room.

This design was well suited to the tropical climate and to the lifestyle expected of a national representative. However, the large open area, characterised by high ceilings, broad archways and white walls, seemed to me rather stark and empty. When I remarked on this fact, my host explained that he had covered the walls with paintings by local artists, but they had already been packed away in preparation for his return to Australia.

It was then that I decided to search for suitable artworks of my own to decorate the house, liven up the atmosphere of the main living areas and provide me with some original souvenirs of my first overseas posting.

“Sub Aqua” by Khin Myint Myint (supplied by author)

My memories of those days are not as clear as they once were, but I can vividly recall my first encounter with the Burmese art world.

Before I began work in the embassy full-time, I was given six weeks to study the Burmese language, with a local tutor. For this period, I stayed in the then 73 year-old Strand Hotel, which was situated just across Seikkantha Street from the embassy, in the heart of the capital. To help get my bearings in a new place, and develop an ear for the unfamiliar sounds and tones of Burmese, I used to take long walks around the city.

It was not long before I came across the Lokanat Art Gallery, around the block from the Strand Hotel, at 58-62 Pansodan Street. The gallery had been established in 1971, in an old Italianate building built in 1906 by Thomas Swales and Isaac Sofaer. Originally known as Sofaer’s Building, it was a prestigious commercial address during the British colonial period, with the Bank of Burma and Reuters News Agency among its tenants.[1]

The gallery was founded by a former military officer and author, Dhammika U Ba Than, and an attorney, U Ye Htoon. They invited 20 leading members of Burma’s art world to become founding members of a cooperative venture. Their aim was to provide a venue for exhibitions and to help contemporary artists make a living from their work, something that had proven difficult since General Ne Win seized power in a military coup in 1962.

Image-making as necessity in Fighting Fear II

A recent exhibition showcased Myanmar artists' responses to the coup and resistance to it.

The Lokanat soon established itself as an important venue for show-casing and selling modern Burmese art.

In early 1974, the entrance to the gallery was easily missed. It was poorly sign-posted at street level and the entrance to the building was crowded with street stalls selling betel nut, slaked lime and other condiments. Also, the exhibition space was on the first floor, hidden away up a flight of dim and dusty stairs. I remember thinking at the time that the old wooden banister was unsafe and could not be relied upon.

To my surprise, however, this rather off-putting entryway led to two very large, airy rooms, with floors covered in attractive antique tiles. The walls were white-washed and hung with colourful oil paintings, water colours and framed sketches. They were by a mixture of established artists like U Hla Shein, who painted in traditional Western styles, and new and emerging artists experimenting with more modern techniques.

Most paintings on display in the Lokanat were portraits, or landscapes. They covered the usual subjects of pagodas, Buddhist monks, paddy fields and bullock carts. These were the timeless, if rather clichéd, themes that had attracted British painters and art lovers from the earliest colonial days, when civil servants, soldiers and tourists developed a taste for artistic works depicting the local scenery and traditional Burmese life.

Painting of a Burmese woman by Gerald Festus Kelly

Indeed, at the hands of painters like Gerald Festus Kelly, Robert Talbot Kelly and Frederick Goodall, paintings of Burmese people and scenes became enormously popular in Britain, the US and elsewhere.[2] Together with photographers like Felice Beato, Philip Klier and others, they helped establish Burma’s reputation as a land of golden pagodas and beautiful women. These romantic images are still being peddled by travel agents.[3]

“On the Road to Mandalay” by Frederick Goodall

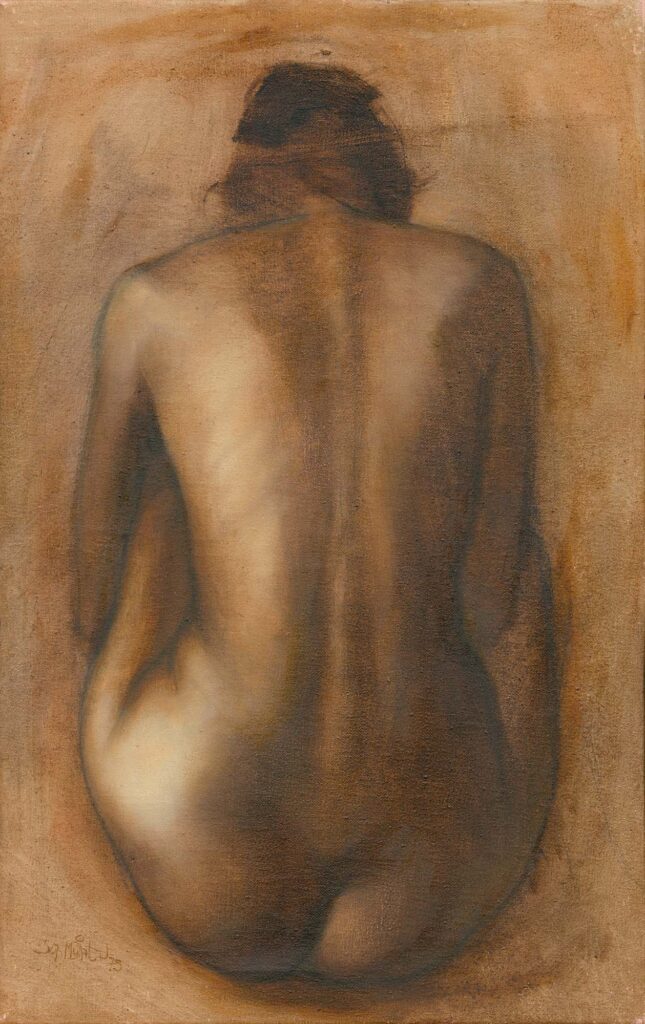

The Lokanat, however, also exhibited other works, by artists with an original approach to styles and materials. One work in my collection by Khin Myint Myint, for example, employed gold leaf to highlight aspects of the figures in the painting. I also have a couple of nudes by Sun Myint, in his trademark sepia and sienna colourings. The latter were purchased privately, however, as censorship of local artworks was then a major issue.

A painting by Sun Myint (supplied by author)

I cannot remember the names of all the artists represented in the Lokanat and the few other galleries operating around that time, but a number stand out in my memory—mainly because I later purchased paintings by them. In addition to works by Sun Myint, Tin Tin Sann, Khin Myint Myint and Ma Thanegi, I acquired oil and acrylic paintings and water colours by the likes of Paw Oo Thet, Win Pe, Tin Win and Sai Kyaw Htin.

Some local artists had received disciplined, formal training in Burma, while others were largely independent and self-taught.

Around this time, there were a number of influential art teachers, like U Lun Gywe, who mentored the young Sun Myint. A few had been abroad, for one reason or another, and could draw inspiration from museums and galleries visited during their travels. Most, however, relied on traditional styles and the realist tradition left behind by the British. Others, however, searched for examples of different genres in art books and magazines.[4]

The primary market for original art works in Myanmar in the 1970s was resident foreigners. Almost all were members of the diplomatic community, then only about 1,200 strong. They were well paid and many were interested in acquiring mementos of a posting in an exotic and relatively remote part of the world. Visitor visas were initially restricted to 24-hours, later extended to seven days, effectively ruling out sales to tourists.

Before my arrival in Burma in 1974, diplomats often staged “free” art exhibitions in their embassies and homes. They were a popular form of entertainment in a city largely devoid of conventional night life. These private functions gave local artists full rein to express themselves, “free” from government restrictions. They were also a welcome source of income for the artists, as few paintings were left unsold at the end of such shows.

These functions, however, aroused the ire of the authorities, who resented the fact that the official censors were being bypassed. Nor did they like members of the local population fraternising with outsiders, particularly the officials of foreign countries, who were always viewed with suspicion. It was suspected, for example, that some diplomats were trying to encourage freedom of expression, something anathema to the socialist regime.

After 1967, free shows on private premises required a government permit, a measure which effectively killed them off.[5] However, this development encouraged local artists and galleries to organise their own exhibitions. Over the next decade there were about three dozen major exhibitions, involving some thirty or so artists.

“Meditation 2” by Khin Myint Myint (supplied by author)

Public exhibitions, however, were subject to heavy-handed censorship. Up to a dozen officials from the government’s Censorship Board and other agencies could turn up to examine the paintings collected for a show, and interrogate individual artists about their work.[6] Needless to say, these officers were chosen for their commitment to the military regime, rather than for any knowledge of, or even interest in, visual art.

Any works that were deemed critical of Ne Win’s socialist government or the armed forces, no matter how remotely, were deemed unacceptable and banned from display. If Burma’s conservative cultural norms were believed violated, for example by the depiction of nudes, they too were banned. Experimental art was also seen as implicitly critical of past ways of life, and thus a challenge to the regime’s isolationist policies.

After the introduction of a new constitution in 1974, and the transfer of power from Ne Win’s Revolutionary Council to a supposedly elected civilian government under the Burma Socialist Programme Party, the level of art censorship in Burma appeared to increase. Even the use of certain colours was considered subversive. Paintings deemed offensive were stamped “not allowed to show” on the front and back. Some works were confiscated and occasionally the artist was even detained.

As Melissa Carlson has written, “in the government’s quest to assert its authority, the censorship of exhibitions soon resulted in a state-sanctioned genus of artwork that drew on idyllic yet conservative portrayals of Burma”. [7] Some more recent observers have admired the perceived emphasis on Burma’s “pastoral, Buddhist-resplendent glory”.[8] However, in the 1970s this trend actually reflected a state-sanctioned template that “stripped canvasses of any real or imagined socio-political commentary”.[9]

Another difficulty faced by local artists around that time was the shortage of materials. Despite strict economic regulations restricting foreign imports, it was sometimes possible to buy paints and canvases from government stores. However, they were always in short supply. Many artists depended on the generosity of foreign friends who were able to bring in paints and canvasses from abroad, usually by visiting art suppliers in Bangkok.

Painting by Tin Tin Sann (supplied by author)

Despite all these problems, however, the artists of the Lokanat Gallery and other outlets, like the Peacock Gallery, continued to work, demonstrating not only their talents for representation and interpretation, but also innovation.[10] Increasingly, Burmese artists experimented with different styles, including cubism and abstract art. The local art scene, while small and isolated from many outside influences, was a surprisingly vibrant one.

During the 1970s, Sun Myint played a significant role in all these developments. In 1971, he became a founding member of the Lokanat Art Gallery. By the time I arrived in Burma three years later, he was already well-established in the local art world, and contributed many original works to the field. Between 1968 and 1977 he participated in at least eight major exhibitions and contributed to a number of shows in private homes.[11]

Along with his sisters Tin Tin Sann and Khin Myint Myint, Sun Myint was also a member of the influential Modernist Movement, which was active in Yangon and Mandalay between the late 1960s and late 1970s.

Sun Myint has been described as a member of the realist school, but I remember him experimenting with other approaches, prompted in part by illustrations he saw in a history book about Western painting. Even his classic works contained hints of other styles. He was also prepared to push the boundaries of official censorship. His nudes, for example, were eagerly sought after by members of the diplomatic community. They were usually painted on canvas set on board, in atmospheric sepia colourings.

One of his paintings stands out in my mind as a good example of Sun Myint’s approach to art at the time. It was titled “The Pilgrims” and depicted a horse-drawn cart, beneath a steep escarpment on which there were several golden and white pagodas [see image above the title of this article]. The scene was finely drawn, with a wonderful use of colour, but what I liked most about it was the creative use of blank space, almost like a traditional Chinese ink painting. This gave the work a wonderful ethereal, other-worldly feel.

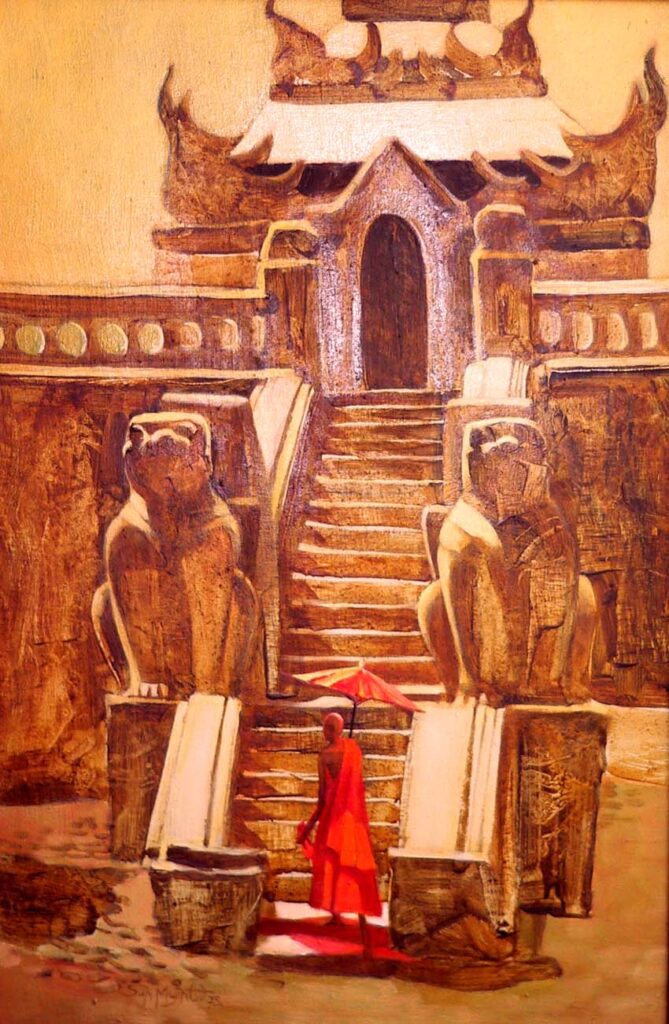

Another acquisition of mine was an oil painting [see below] of a Buddhist monk on the steps of the Pitakat-Taik, in the ancient capital of Pagan (now Bagan). It stands apart from other paintings in this genre by Sun Myint’s distinctive use of a yellow/brown/red palette, with colours ranging from cadmium yellow to burnt sienna. Also, the edges of the building and the standing figure are softened, and the differences between light and shadow are emphasised, to give a distinctly impressionistic feel to this timeless scene.

A painting by Sun Myint (supplied by author)

Tin Tin San’s paintings covered a range of genres, but my eye was caught by one in particular. It was an impressionistic oil painting of boats on Pazundaung Creek, near my home on Monkey Point Road. Like her other paintings with a maritime flavour, it is a vibrant and evocative work, relying heavily on light sienna and other rich earth colours to capture the images of small boats moored by a jetty, with light shimmering on the water.

A painting by Tin Tin Sann (supplied by author)

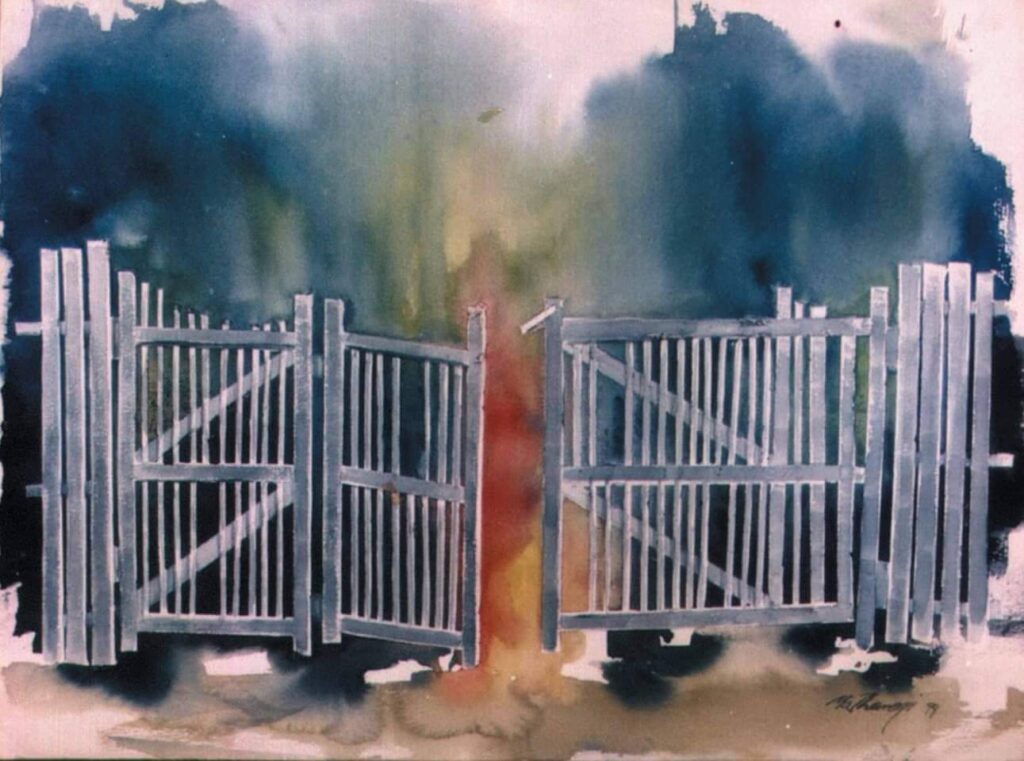

Ma Thanegi too had a fine eye for form and line, and could paint highly accurate and realistic still life and landscape paintings, and portraits, in both oils and water colours. However, like her friend Khin Myint Myint, she too experimented with other art forms, including the use of different mediums. I still have a large framed batik of a bilu (Burmese ogre) she made during one of her forays into the craft world.

Painting by Ma Thanegi (supplied by author)

Painting by Ma Thanegi (supplied by author)

Painting by Ma Thanegi (supplied by author)

These days, I do not have the wall space in my modest suburban house to hang all my Burmese paintings. Some works have been returned to their creators and a few have been given away as gifts. However, those paintings that remain are potent reminders of those far-off days when I was a neophyte diplomat gradually getting to know an exotic, if tragically misgoverned, land through the medium of its artists and visual art.[12]

References

To return to your place in the text, click the footnote number

[1] Association of Myanmar Architects, 30 Heritage Buildings of Yangon: Inside the City that Captured Time (Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2012), pp.81-5.

[2] More than 50,000 prints of Gerald Kelly’s portraits of Burmese “princess” Sao Ohn Nyunt have been sold. They are still available today. See Christian Gilberti, “An Irish Painter in Burma: Sir Gerald Kelly”, Myanmore, 4 March 2020, at https://www.myanmore.com/2020/03/an-irish-painter-in-burma-sir-gerald-kelly/

[3] Andrew Selth, Making Myanmar: Colonial Burma and Popular Western Culture (revised version), Research Paper (Brisbane: Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University, 2020).

[4] For example, one monochrome painting by Paw Oo Thet, of a female Burmese dancer, was reportedly inspired by “The Peacock Skirt”, a print by the 19th century British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.

[5] Andrew Raynard, Burmese Painting: A Linear and Lateral History (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2009), p.216.

[6] The Censorship Board was overseen by the Press Scrutiny and Registration Department of the Ministry of Information. It was staffed on a rotating basis by appointees from a range of government departments and security agencies. See Ian Holliday and Aung Kaung Myat (eds), Painting Myanmar’s Transition (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2021), p.6.

[7] Melissa Carlson, “Painting as Cipher: Censorship of the Visual Arts in Post-1988 Myanmar”, Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, Vol.31, No.1, March 2016, pp.116-72.

[8] Peter Janssen, “Golden Land Unveiled”, Asian Business, April 1995, p.63.

[9] Carlson, “Painting as Cipher”, p.121.

[10] The Peacock Gallery opened in 1975 and closed in 1986. While small, with only nine members, it had a major impact, in part through exhibitions of works using such diverse mediums as batik, papier decoupages and collage. See Ma Thanegi (ed), Myanmar Painting: From Worship to Self-Imaging (Ho Chi Minh City: Education Publishing House, 2006), p.76.

[11] Raynard, Burmese Painting, p.217.

[12] Andrew Selth, “Burma After Forty Years – Still Unlike Any Land You Know”, Griffith Review, 26 April 2016, at https://www.griffithreview.com/wp-content/uploads/Selth.Burma_.Essay_.Final_.set_.pdf

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss