On 12 November 1994, a group of 29 young Timorese men gathered to protest outside the US embassy in Jakarta. They were there to make sure the world did not forget what happened at the Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili on the same day three years earlier: a massacre of more than 250 Timorese civilians by Indonesian troops.

As the Indonesian police arrived on the scene, the protestors jumped the fence seeking sanctuary from their batons. This act turned a fleeting protest into 12-day long occupation of the embassy’s parking lot. While world leaders, including US president Bill Clinton, were set to meet for the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Bogor, these members of the clandestine Timorese resistance pulled off a diplomatic coup by focusing international attention not just on the Indonesian economic miracle but also on the unfinished business of its illegal occupation of East Timor.

On 12 November last year I was in Dili, where at night residents lit the footpaths and streets with candles remembering the people killed in the 1991 Santa Cruz massacre. It is a day of symbolism and reverence in Timor-Leste: a day of tragedy, but also arguably a turning point in the resistance and the international struggle for recognition and independence. My first reporting on the country as a young journalist started after the massacre, which is now memorialised as a pivotal event in the narrative of Timor-Leste at the Timorese Resistance and Archive Museum. On the day I visited the museum its halls were mostly quiet. I was the only visitor, giving the place feel of a shrine. In the exhibit on Santa Cruz, the eerie soundtrack of wailing sirens from Max Stahl’s footage, which immortalised the day of the massacre, the only sound.

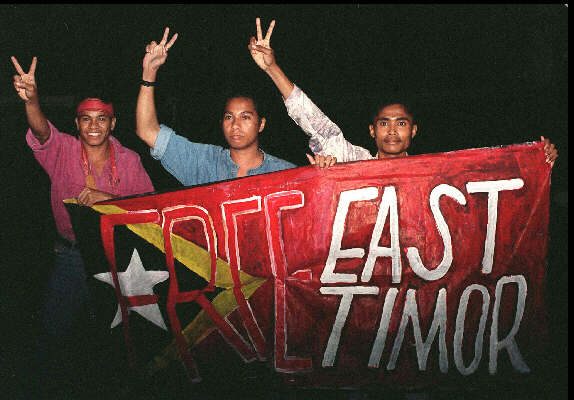

The museum also has a larger-than-life art installation remembering the “storming” of the US embassy in Jakarta, which creatively immortalises in the moment the protestors broke into the embassy to bring the world’s attention to the violence of Indonesian occupation in the wake of Santa Cruz. It gives the individual act of each of the fence jumpers significance in the broader arc of the resistance. One super-sized man hurdles the fence. “East Timorese youth storm the US embassy in Jakarta and demand the release of Timorese prisoners,” reads the caption.

But why is this the only text in the exhibit on what was one of many embassy invasions, protests, and asylum bids over many years? Entering embassies in Jakarta was a tool and tactic of the clandestine movement used frequently, involving hundreds of people. But in the museum, this is the sole mention. Each single jump was a personal and political act, responding to and often escaping from the repression Indonesian rule, which between 1976 and 1999 administered Timor Timur—East Timor—as its 27th province. Foreign correspondents called them “break-ins” as they were illegal acts and unlawful entries onto protected diplomatic premises. But they served different purposes as protests, escape routes, and ways to raise voices of Timorese in international negotiations over the region’s future.

As an accredited foreign correspondent in Jakarta between 1994 and 1998, I saw and reported on many of these break-ins. So many, in fact, the French ambassador once accused me of being part of the clandestine movement. My personal archive from those days holds many of these reports but not records of all these incidents. Over the years, I have been adding documents on my cloud drives. I have told stories over Portuguese wine that never made the wire. It was while recounting these tales last year in Dili that a Timorese friend urged me to write more of them down before we all forgot them. By doing so, I hope to distinguish art from history and fact from recollection and add to what is publicly known about this part of Timor-Leste’s struggle for independence.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

In November 1994 I was new to the beat, and late to the US embassy protest. Less than six weeks on the job as an Agence France Presse (AFP) correspondent, I did not have good sources. While reporting the news from East Timor was a central part of my job, the clandestine movement were not in my contact book, and none of its operatives knew my name. I was only there at all because on the day Timorese activists had decided that our rival Reuters should not have an exclusive. More publicity was good for the cause.

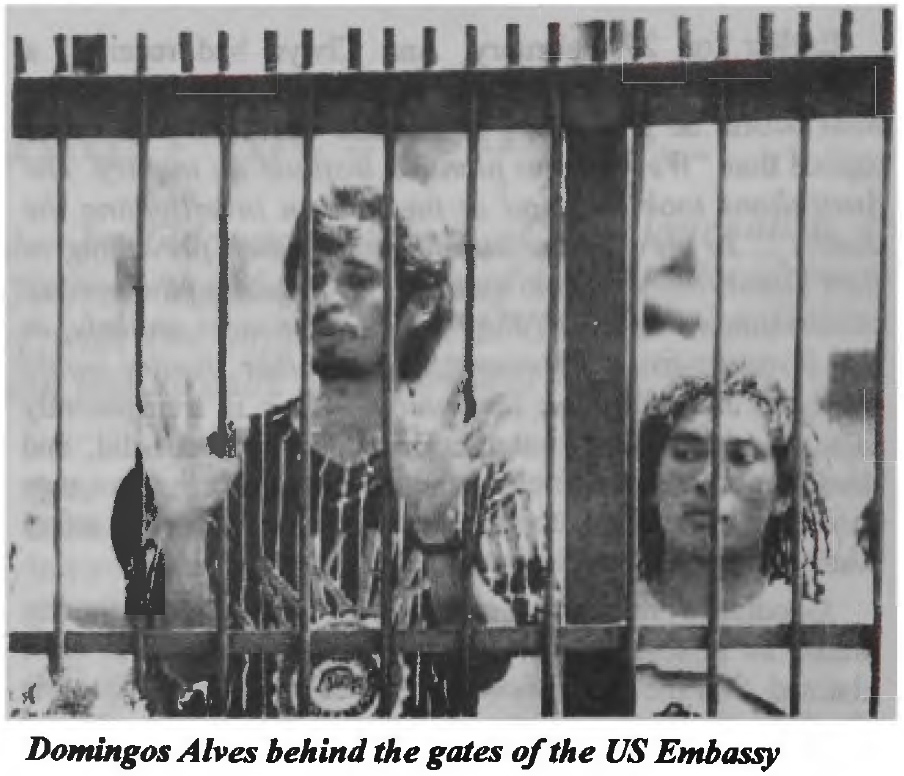

On this Saturday morning, leaders from RENETIL, the Timor-Leste Students’ National Resistance, delegated one of their number to anonymously tip off AFP and the BBC, co-located in a bungalow on Jalan Indramayu. The embassy was 10 minutes away in a three-wheeled orange Bajaj taxi. I arrived without a photographer or camera as the police moved in. Thinking on their feet, initially the 28 protestors scrambled over the fence to evade arrest. “It was not our intention to enter the embassy grounds at all,” RENETIL leader Domingos Alves said in an interview with TAPOL Bulletin.

However, after the police intercepted a large group of Timorese traveling from other parts of Java by train, Alves, who was the group’s spokesman, told TAPOL the protestors lost their element of surprise. Many of them were on their first trip to Jakarta and had no idea the train trip would end with a flight to Portugal. Research by Edie Bowles, who is writing a history of the Timorese resistance, has found only Alves and one other RENETIL leader discussed jumping the fence and seeking asylum ahead of time, and only as a response to rapid police action. The protestors arrived at the embassy with journalists and the police waiting for them. Suddenly, the RENETIL leaders put their Plan B into action.

Once in the embassy, with APEC to start within days, the protestors had the spotlight, a platform, and a captive audience of international journalists in town for Suharto’s party. For ten days they held court, with Alves briefing us three times a day with demands to meet President Clinton and free East Timor. The occupation of the US embassy was a mentioned in every news story as the “leader of the free world” came and went.

But once APEC passed, so did the world’s attention. The Timorese initially told us they did not want asylum, but after embarrassing Suharto it was a safer choice than being handed over to the police. Delegates from International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC) in Jakarta negotiated safe passage for the original 28, and one more protestor who had audaciously jumped in later. I watched and filed on my Nokia brick phone as the ICRC bussed them to Jakarta’s airport and onwards to “repatriation” to Portugal, a country none of them had visited, but which regarded all Timorese born before 1983 as being its citizens.

In its lengthy history of the conflict, the Report of the Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation (CAVR), Chega!, has two paragraphs on the embassy break-ins, writing that Timorese students turned many foreign embassies in Jakarta into fortresses as they jumped fences to seek asylum. The protest at the US embassy was a “stunning public relations success organized by RENETIL.” The Chega! findings are based testimony of RENETIL members, including Virgilio Gutteres, Avelino Coelho, Naldo Rei, and Mariano Sabino Lopes, the current deputy prime minister. It said the break-ins were a well-coordinated strategy that the student group executed in in coordination with Xanana Gusmão, with whom they had direct and regular access during his detention at Jakarta’s Cipinang prison. The report only mentions three actual incidents: the US embassy break-in, a November 1995 asylum claim at the French embassy, and December 1995 protests at the Russian and Dutch embassies. The CAVR did not tally the numbers of those who entered the embassies either seeking asylum or to protest.

It is an understated reference to a movement that involved hundreds of people over more than a decade. From TAPOL Bulletins archived online by Victoria University and my own reporting, I know asylum bids were unsuccessfully made at least four occasions before events at the US embassy. The first bid I found was from October 1986 when four students, released from detention, sought asylum in the Netherlands embassy, which in those days represented Portugal’s diplomatic interests in Indonesia. TAPOL reported that the asylum bid was unsuccessful, writing the Timorese were “tricked” into leaving after being promised Portuguese passports later. In June 1989, TAPOL recorded another attempt by six Timorese students on the run to seek refuge in the Japanese, Swedish, and Vatican embassies was “callously” rebuffed. The first successful asylum bid was when on 23 June 1993 four Timorese entered the Finnish and three the Swedish embassy. The ICRC quietly arranged travel documents for the seven to travel to Portugal on 29 December that year after on “humanitarian grounds.”

After the November 1994 US embassy sit-in, the next known incident was on 25 September 1995, when five men identified as having survived the Santa Cruz massacre entered the British embassy in Central Jakarta. After five days, the ICRC flew them to Portugal. In quick succession, on 7 November eight entered the Netherlands embassy, then on 14 November, as APEC leaders were meeting in Japan, 21 jumped the Japanese embassy fence on Jalan Thamrin. Five others from this group, jumped the French embassy fence across the road on 16 November. With practice, it became a well-oiled machine: a pre-dawn break-in could lead to an evening KLM flight.

Population loss in Portuguese Timor during WW2 revisited

A new archival find suggests that Japanese occupation was more devastating than previously thought

Days later, on 7 December 1995—the 20th anniversary of Indonesian invasion of East Timor—arge groups of Timorese and Indonesian activists jumped into the embassies of Russia and the Netherlands as a protest and not an asylum bid. Shouting “Free Xanana Gusmão”, 58 activists entered the Dutch embassy in Kuningan; on Jalan Thamrin, 47 jumped the low fence at the old Russian embassy, next to the Japanese and across the road from the French missions. I reported that police blocked 19 protestors who had tried to enter the French embassy at the same time.

With their point made and reported, police escorted the protestors off the premises of the Dutch and Russian embassies within two or three days, interrogated and then released them. Once again, RENETIL activists armed only with banners and their own quick wits and collaborating with Indonesian counterparts, including from the People’s Democratic Party (PRD), were reminding the world of the Suharto regime’s repression, and the ongoing occupation of East Timor.

In 1996, asylum bids continued. On 12 January, five young men entered the New Zealand embassy, and two women entered the Australian embassy seeking asylum. The ICRC quickly organised their passage to Portugal with three days. On 18 March, as Timorese leaders gathered to meet for an UN-sponsored dialogue in Austria, two young men sought refuge in each of the Polish and French embassies. Around this time, I recall that still others went into the Spanish embassy on Jalan Wahid Hasyim behind the Sarinah department store—I recently met one of those men in a Dili restaurant, but cannot find records of ever having reported this 1996 incident.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

The waves of asylum bids and the ease with which Timorese could enter embassies was a growing concern of the Jakarta diplomatic community. They began by hardening their buildings, extending fences, adding razor wire, and allowing local security guards to be more aggressive in their responses. On 16 April 1996, local guards beat and expelled ten Timorese asylum seekers who entered the German embassy in front of a Reuters TV crew. After the ICRC intervened, the young men went to Portugal.

On 16 October 1996 I got an early morning pager message from my clandestine contact “Ran”, who I now know as Timorese journalist Naldo Rei. Either using this way, or a message on my answering machine, he would alert me a break-in was imminent hours before it was set to take place. By this time, we had a routine: Naldo would tell me where and when an asylum bid would take place, and I would show up and report it.

On this day, I remember walking from my apartment on Jalan Kebon Sirih to the French embassy on Jalan Thamrin. We all knew the drill. Using my point and shoot Nikon that I always carried on my hip, I photographed the three men with their banner and their ID cards (KTPs) to prove the bona fides as Timorese. Tape recorder in hand, I asked them why they were there. “We are seeking political asylum in Portugal. We feel that our homeland has been taken over by the Indonesian military,” one of the men, who identified himself as Sabino D’Arujo, 26, told me. “In East Timor we are always chased by the troops of the Suharto regime,” said a second man, named as Alberto Da Silva, 23. I reported the third man as Anatolio Francesco Arujo, 21.

After recording their words, I walked back to the Reuters bureau on Jalan Merdeka Selatan. It was early, so I filed the story to the London desk and before going for a morning swim at a nearby hotel. I arrived at the bureau for the regular day around 8am to the news from the Hong Kong desk that our rivals at AFP were reporting that the French embassy had ejected three “Javanese thieves”. We quickly developed the film from that morning’s break-in and put on the wire pictures of three “thieves” holding a Free East Timor flag. It was embarrassing for my former AFP colleagues, who had accepted the embassy’s “official” version of events. The ICRC head of delegation was livid and publicly chastised the French. I understood that days later these three men were all on their way to Portugal through other embassies with the ICRC’s help.

Reuters regarded each break-in as an international diplomatic incident worth reporting. Under directions from my bureau chief Ian Mackenzie, I was to cover them all. I would get up in the dark to confirm the break-in with my own eyes and put it on the wire. Years later Naldo would explain our source–reporter relationship in this way: “you cared, you kept on showing up, so we kept on calling you.” While we did not always report it, if we could speak with asylum seekers, we did take down the names and photograph their ID cards. When contacted, we shared them with human rights groups tracking these incidents.

The French ambassador was suspicious of how I was always there and told a meeting of his EU colleagues that I was a member of the clandestine movement organising the break-ins. After the UK embassy told us about this, my boss complained, and the French envoy withdrew his claim. I was under orders: report every one of them. For my stories on East Timor, senior officials in the Indonesian information and foreign ministries twice threatened me with expulsion. Once again, when called by my boss, they explained away the threat as a “misunderstanding.” As a partner of the national news agency Antara, Reuters’ business news service was a cash cow for the State Secretariat that they were reluctant to upset, and this gave us some protection to report uncomfortable truths about Indonesia under Suharto.

If we did not receive tips, and embassies did not talk, we could not report a break-in. This means it was hard to understand how many bids were unsuccessful. I have breadcrumbs in my reporting of references to Timorese asylum seekers being ejected from the Hungarian, Dutch, and Swiss embassies by security guards throughout October 1996, but no separate reports. The Timorese were a nuisance, and embassies did not want to show sympathy or solidarity for their cause. I do not have access to Reuters database and cannot find all my stories, including the one of the expulsions of Timorese by the head of the Palestine Liberation Organization from his Menteng office and residence. However, I still remember his words: “I told them if they try again, I will shoot them.” It was no idle threat, as we knew he was armed. “I thought they were Mossad agents,” I recall him saying.

On 25 March 1997, 33 Timorese students broke into the Austrian embassy while UN envoy Jamsheed Marker was in Jakarta to talk to the government about East Timor. The students demanded to meet Marker, and after a small delegation were able to deliver a petition, they all left. The last asylum bid I have records of took place on 19 September 1997. After Timorese bomb makers in Central Java had an accident, they blew the cover on the Black Brigade, a small unit engaged in buying ammunition and other supplies for the resistance lead by Avelino Coelho da Silva. Together with his wife and three children, Coelho and Nuno Saldanha evaded capture and made it to Jakarta and to sanctuary in the Austrian embassy. This was Coelho’s second attempt at asylum, as he had been in the unsuccessful June 1986 group. The modus operandi that had worked so well with ICRC was over. This time Indonesian authorities stood firm as the security forces wanted these “terrorists.” Authorities refused to allow them to leave for Portugal. This underground railway had come to the end of the line.

My reporting is incomplete and TAPOL, which based in London and relied on our stories, has few other reports on asylum bids in 1996 and 1997. Around this time, my contact Naldo left to study in Australia and the tips abruptly stopped coming. The political and economic plates in Indonesia were shifting after the New Order apparatchiks orchestrated an internal party coup to destabilise Megawati Sukarnoputri and her opposition PDI. The regime used the PRD as scapegoats for the Jakarta riots of July 1996. They underlined the fragility of Suharto’s rule, even after Golkar easily won the May 1997 elections, setting up another term in office for the former general. In August 1997, Bank Indonesia floated the rupiah, and krismon—the Asian Financial Crisis—was underway. The story was now the how and when of Suharto’s demise, which came in May 1998 after widespread rioting. Amid the chaos and news overload, the Timorese in the Austrian embassy quietly left, probably with the ICRC’s help, when we were not paying attention.

The ICRC was always modest and diplomatic about their role in helping Timorese asylum seekers. They played a much bigger role than I knew at the time. As research for this piece, I reviewed two decades of ICRC annual reports and the organisation’s data is neither consistent nor complete. A January 1994 press release, for example, records the six asylum seekers they facilitated leaving in December 1993 after almost six months in the Swedish and Finnish embassies, but it is not mentioned in the 1993 annual report.

The ICRC’s 1994 Annual Report notes the role its Jakarta delegation played in resolving the US embassy incident by facilitating the departure of the 29 protestors to Portugal and how it had an ongoing role in following the cases of Timorese in Jakarta, “including those who had been prevented from joining the group in the United States embassy compound.” In 1995, after “the Timorese sought asylum in the embassies of France, Japan, the Netherlands and Russia. They were all subsequently transferred to Portugal under ICRC auspices”, but it does not say how many left. The following year the delegation “organized the transfer to Portugal of 189 East Timorese (former civil servants in the Portuguese colonial administration and hardship cases) who had sought asylum in foreign embassies” but does not say from which missions they came. In 1997, the ICRC said it “organized the transfer to Portugal of 38 East Timorese” followed by another 34 in in 1998.

By 1999, the asylum bids had stopped as ICRC’s delegations in Jakarta focused the mediating the violence ahead of the August independence referendum in East Timor and delivering humanitarian aid after the crisis it triggered and during the transition to UN administration. While I was aware of 122 Timorese they helped to leave Jakarta embassies, their stated figures of 296 repatriations to Portugal are more almost two and a half times of what I knew of as a reporter.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

30 years later, not all of them came back. But when in Dili I still bump into those who jumped the Jakarta embassy fences and the clandestine members who organised it. I never heard again of the three “Javanese thieves” in the French Embassy. I hope they are middle aged men with families now, as I am. When I worked in the office of the UN Transitional Administrator, I would sit across from Coelho, a member of the National Consultative Council and head of the Timorese Socialist Party (PST). Whenever I visited his office, he always had a copy of Das Kapital within reach.

Once, at a US embassy reception, I ran into the RENETIL leader and US embassy sit-in spokesman Alves, when he was then a foreign affairs advisor to the Timor-Leste president. In a historic irony, in 2014 Alves was appointed as Dili’s ambassador to Washington, D.C. Arsenio Bano, who was also in the US embassy in November 1994, became a FRETILIN minister for social solidarity, and I worked within him as he led Timor-Leste NGO Forum, an umbrella organisation for civil society. Last year I had coffee with him on his last day as the President of the Special Administrative Region of Oé-Cusse Ambeno (RAEOA).

When Rei and I were recently going to eat in Dili, we ran into one asylum seeker who was then an ambassador to ASEAN country. Gutteres, the tipster who told me of the US embassy protest, is the Ombudsman for Human Rights and Justice. Gil outed himself to me years ago, but when I last saw him in Dili, we had time for a coffee, a chat, and even a Zoom call with my wife. It was not just the few hurried words over the phone in Jakarta on the morning of 12 November 1994.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss