If we are to look beyond royals to compile a list of the ten Thai civilians who have been the most popular subjects of writing—both Thai and foreign—on the ideas of Thai political thinkers, the name Sulak Sivaraksa could not be omitted.

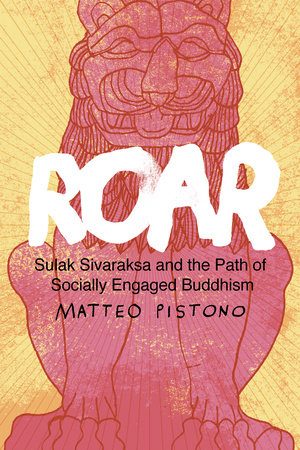

Roar: Sulak Sivaraksa and the Path of Socially Engaged Buddhism is yet another work among dozens describing the life, political thought, social contributions and religion of Sulak. Some past volumes critique the limitations and weaknesses of Sulak’s political theorising. Other volumes, written by his students and peers, are perhaps overly deferent and have the effect of placing Sulak on a high pedestal, and linger only on minor quibbles.

Roar offers something new: self-reflection and a picture of Sulak in his own words, contextualised against the world that surrounds him. Matteo Pistono’s primary concern is neither to critique nor to flatter, but to offer Sulak room to describe himself, so that the reader may decide for themselves how to view him.

Pistono—himself a Buddhist—is a prolific writer and interested in “socially-engaged Buddhism” himself (his past works include a biography of a senior Tibetan monk). If Pistono was seeking to write a life history of somebody with a spirit not far from his own, he could have done far worse than settling on Sulak Sivaraksa, who is known as the “father of socially-engaged Buddhism”.

It should be noted that, numerically speaking, Sulak’s followers are on the decline. Moreover, his writing in recent years has been less egotistical. He writes about himself less, in favour of speaking about other people, such as deceased friends. Instead of presenting his own judgements, these days he seems to prefer raising passages from favoured books. It is increasingly difficult to patch together a sense of Sulak’s “voice” from his own writing.

In this context, Roar offers a consolidated volume for readers, especially those from younger generations, to get acquainted with Sulak Sivaraksa. Roar chronologically documents the figure’s life from his childhood, his time studying in the United Kingdom, his editorship over the Social Science Review, his creation of a school of socially-engaged Buddhism, until his contemporary senior years.

The first chapter of Roar begins with the heady drama of Sulak’s escape from Suchinda Kraprayoon, the head of the National Peace Keeping Council from 1991, with the assistance of Lao civil society leader Sombath Somphone. From Laos, Sulak flew with a fake Lao passport to Russia, and then onwards to Sweden. This is no boring biography: it describes a Buddhist who engaged in risky and rigorous critique of a military government, and who was forced to flee his country for doing so.

Pistono then describes Sulak’s childhood years in deep detail, offering insight into the influence of his father, mother and the environment around him. Sulak grew up during a period of dramatic changes in governance, when pro- and anti-royalists were sharply divided. The influence of his father and teachers at Wat Thong Nopakhun set him towards conservative leanings. He admired royal figures, such as Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, more than his foreign-educated peers such as Pridi Banomyong did. When it came to Western traditions, Sulak was always more interested in the Roman and Geek empires, than the enlightenment or reason-based philosophies.

Pistono’s biography may elicit in readers more feelings of relatability than Sulak has allowed in his Thai-language writings. By way of analogy, the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej once hired a writer who he admired to compile his biography, who candidly recorded the things that the King confessed. People possessing great barami seem to be fond of employing writers to compile biographies that are distributable abroad, but which are banned domestically due to the need to gloss over certain truths. It’s not only Bhumibol who chose to speak frankly with foreigners more so than Thais. Pistono writes that Sulak once remarked that even former foreign minister and Democrat Party leader Thanat Khoman sometimes flew to France for the purposes of conversation, while the prince and diplomat Wan Waithayakon appreciated the easiness of speaking in English, free from the complexities of royal language.

Insofar as there are some issues that cannot be discussed in Thailand, Roar is in some ways similar to the biography of Bhumibol penned by William Stevenson. The result of both endeavours may eventually be the same: it may not be possible to translate them into Thai in a way that is permissible under the law. In Roar’s case, the sensitivity is not due to the confessing of personal information that cannot be the subject of public discussion, but the discussion of Thai socio-political history as well as the monarchy institution. Though Pistono states that he compiled the research for the book himself, it remains the case that most of the book is framed by the viewpoint of Sulak (this is obvious from the emphasis on Pridi Banomyong, or a number of passages that are framed as Sulak would likely have written them—that is, with a marked emphasis on the relationships between certain political actors).

The book’s conclusion seems to contain messages that Sulak would like to impart to the current monarch:

“I failed to save the monarchy from corruption, and from being irrelevant to the common man. I tried to warn the King in so many ways for many decades, but he never listened.. It’s the same advice that everyone needs. He needs kalyana-mitta who will tell him what he doesn’t want to hear. He must listen to voices of criticism. The more powerful one becomes, the more transparent they need to be. Judging by the lack of kalyana- mitta around the late King Bhumibol, Sulak was not hopeful that the new king, Vajiralongkorn, would ever hear any criticism. And this lies at the heart of Sulak’s greatest disappointment in life—his failure.”

We would not be able to see him speak in such a way in the Thai-language universe. Even though Sulak is known for his frankness and refusal to bow down, the Thai-language universe limits even some of his freedoms.

While researching the biography, Pistono did the due diligence of any good biographer by travelling with Sulak to various locations both in Thailand and around the world, interviewing other biographers, and interviewing disciplines of Sulak and those close to him. The effect is a detailed tapestry of Sulak’s life. A side-effect of that closeness is a certain deference. That Pistono views Sulak as a “teacher” in the Buddhist sense of the word is perhaps one reason he tried to document Sulak’s life “in his own words” more so than offering his own judgements and critiques.One aspect of Sulak’s life that Pistono arguably skims over is his work as an editor, a profession which must have shaped his overall character. Though Sulak no longer oversees the Social Science Review, he published books throughout his life and was the editor of several books and magazines (today, he is still a patron of Seeds of Peace and Pajarayasara magazines). Editing books on political and social issues inevitably involves listening and digesting a diversity of opinions, and the capacity not to be overly attached to any branch of ideology (though Sulak liked to push the provocative argument that liberty forms the foundation of democracy more so than elections). And in the context of social change, Sulak’s editing did not stop with books—the various organisations he was involved in founding succeeded or failed on the various networks that he cultivated and chose. All of his life’s work involved editing.

Despite his liberal ideology, Sulak once said that to be an editor is to be a dictator, because in the end the editor makes the final call. No small number of people view Sulak as a figure riddled with self-contradiction. Even many readers in the West are perplexed by his criticisms of the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh or his preaching to the Dalai Lama not to drink Coke. Yet it remains that case that he holds the status of a leading figure in Thai society. Reading Sulak’s biography raises the question of whether such self-contradictions are merely a fact of human life, and are merely especially salient in the personality of someone who has edited the writing of others all his life. And so it is that Pistono invites Sulak to “roar”, leaving it to the reader to make up their own mind.

ในบรรดางานศึกษาทั้งไทยและเทศเกี่ยวกับความคิดทางการเมืองของบุคคลที่น่าสนใจชาวไทย หากตัดรายชื่อพวกเจ้าออกไป (เช่น ร.5 ร.6 และร.9) คนไทยธรรมดาสามัญที่มีงานศึกษากล่าวถึงกว้างขวางที่สุดในสิบอันดับแรกย่อมต้องมีชื่อ สุลักษณ์ ศิวรักษ์ หรือ ส. ศิวรักษ์ อยู่ในนั้น

หนังสือเล่มนี้เป็นอีกเล่มในบรรดาหนังสือค่อนร้อยที่กล่าวถึงชีวิตภูมิหลัง ความคิดทางการเมือง สังคม และศาสนาของ ส.ศิวรักษ์

ในบรรดาหนังสือค่อนร้อยที่กล่าวนั้น บางเล่มอาจจะกล่าววิจารณ์ความคิดทางการเมืองของส.ศิวรักษ์ ว่ามีขีดจำกัดอย่างไร มีจุดอ่อนตรงไหนบ้าง บางเล่ม ลูกศิษย์และมิตรทำให้ก็อาจจะเกรงใจอยู่ในทีจึงมีลักษณะชื่นชมและยกย่อง ส.ศิวรักษ์ อย่างสูง อาจจะมีวิจารณ์อยู่ให้เพียงแค่แสบๆคันๆ หนังสือเล่มนี้นั้นมีความพยายามที่แตกต่างออกไป กล่าวคือ เป็นหนังสือที่ให้ ส.ศิวรักษ์ ได้พูดถึงตัวเอง สะท้อนตัวเอง ขณะเดียวกันก็ฉายบริบทแวดล้อมของส.ศิวรักษ์ ให้ผู้อ่านได้เห็น ลีลาการเขียนของผู้เขียนไม่ได้มุ่งเน้นที่การวิจารณ์ หรือสรรเสริญเยินยอ แต่โดยรวมไปในลักษณะบรรยายในสิ่งที่ ส.ศิวรักษ์ เป็น ให้ ส.ศิวรักษ์ เดินเรื่องเอง ให้คนตัดสินกันเองว่าควรจะมองมนุษย์คนนี้อย่างไร

Matteo Pistono ผู้เขียนหนังสือนี้เป็นนักเขียนที่มีชื่อเสียง เคยเขียนชีวประวัติพระเถรานุเถระชาวธิเบตอยู่ก่อนแล้ว ทั้งเป็นพุทธศาสนิกที่สนใจพุทธศาสนาเพื่อสังคมอยู่ด้วย หากเขาสนใจใครจนถึงขนาดเขียนเป็นชีวประวัติในประเทศไทยและในโลก หากจะมีใครมีคุณสมบัติพอแล้ว ทั้งมีจริตที่ไม่ห่างไปจากเขา ย่อมไม่พ้นที่เขาจะเห็น ส.ศิวรักษ์ ซึ่งเป็นนักเขียน บรรณาธิการ พุทธศาสนิก ผู้ได้รับการขนานนามว่า บิดาแห่งพุทธศาสนิกชนเพื่อสังคม เป็นหนึ่งในคนที่น่าสนใจเขียนชีวประวัติ (ร่วมกับติช นัทฮันห์)

เมื่อเขาทำการศึกษา ส.ศิวรักษ์ PIstono ทำตามนักเขียนที่ดีทั่วไปในการเดินทางไปกับ ส.ศิวรักษ์ ยังที่ต่างๆ ทั้งในประเทศไทยและทั่วโลก สัมภาษณ์ตัวผู้เขาเขียนประวัติและสัมภาษณ์ลูกศิษย์ลูกหา คนรู้จัก เพื่อให้ภาพฉายออกมาให้เห็นมากที่สุด กระนั้นความยำเกรงของความใกล้ชิด การที่ส.ศิวรักษ์ เขามองเป็น ‘อาจารย์’ ในความหมายเชิงพุทธ ก็น่าจะเป็นเหตุผลหนึ่งด้วยกระมังที่ทำให้เขาพยายามให้ หนังสือเขาเป็น ของส.ศิวรักษ์ มากกว่าที่เขากล้าเอาตัวเองไปวิพากษ์ประเมินค่าใดๆ

Roar เปิดปฐมบทอย่างน่าตื่นเต้นให้ผู้อ่านเห็นตอนที่ ส.ศิวรักษ์ หนีสุจินดา คราประยูร หัวหน้ารสช ไปยังประเทศลาว โดยมีสมบัติ สมพอน ผู้นำภาคประชาสังคมลาวให้การช่วยเหลือ ก่อนจะขึ้นเครื่องบินโดยใช้พาสพอร์ตปลอมจากลาวไปยังรัสเซีย และเดินทางไปสวีเดน นี่ย่อมทำให้คนที่คิดว่า คนเอเชียคนนี้ไม่ธรรมดา และยิ่งเป็นพุทธศาสนิกชนด้วยแล้ว การที่พุทธศาสนิกชนวิพากษ์วิจารณ์รัฐบาลอย่างรุนแรง และหลบหนีออกมาอย่างดุเดือดคงไม่ใช่เป็นหนังสือชีวประวัติพุทธศาสนิกที่น่าเบื่อแน่ๆ และมุมมองของเขาก็น่าจะน่าศึกษาอยู่ไม่น้อย

สำหรับผู้อ่านที่เป็นชาวไทย หากติดตามอ่านหนังสือของส.ศิวรักษ์ โดยเฉพาะงานช่วง 20 – 30 ปีก่อน หนังสือเล่มนี้ช่วยให้พวกเขาจำได้ถึงสิ่งที่ ส.ศิวรักษ์ เคยลอกคราบตัวเอง วิพากษ์วิจารณ์ตัวเองแสบๆคันๆ ผ่านคนที่มาสัมภาษณ์ชีวิตของเขา หรือในหนังสืออัตชีวประวัติสองเล่มใหญ่ที่เขาเขียน แต่พูดกันในเชิงคณิตศาสตร์ จำนวนคนเหล่านั้นก็ลดน้อยถอยลง คนที่จะรู้จักส.ศิวรักษ์ คนรุ่นใหม่ในปัจจุบันซึ่งน่าจะมาเป็นกลุ่มแทนที่คนรุ่นก่อนหน้ายิ่งขึ้นทุกที ถ้าหากได้อ่านงานของ ส.ศิวรักษ์ ในช่วงระยะหลังนี้ เขาจะเห็นชีวิตของส.ศิวรักษ์ ที่มีความเป็นอัตตานิยมน้อยลงทุกที ส.ศิวรักษ์ พูดถึงตัวเองน้อยลง แต่พูดถึงคนอื่นมากขึ้น (เพื่อนๆเขาที่ชีวิตหาไม่แล้ว) และยกบทความจากหนังสือดีๆ มากกว่าใส่ความเห็นตัวเอง การปะติดปะต่อชีวิตของส.ศิวรักษ์ ผ่านหนังสือของเขามี “เสียง” ของเขาน้อยลงไปทุกที ฉะนั้นการดำเนินเรื่องของหนังสือเล่มนี้ที่กล่าวเรียงลำดับเวลาจากเด็กนักเรียน นักศึกษาที่อังกฤษ บรรณาธิการสังคมศาสตร์ปริทัศน์ ทำกลุ่มพุทธศาสนิกชนเพื่อสังคม มาจนถึงวัยชราก็น่าจะทำให้ผู้อ่านโดยเฉพาะคนรุ่นใหม่ได้รู้จักกับ ส.ศิวรักษ์ ได้ดีขึ้นนอกเหนือการรู้จักอ่านงานเขียนของเขาสองสามเล่ม (โดยการประชาสัมพันธ์ชวนเชื่อจากเพจเฟซบุ๊กของส.ศิวรักษ์ ที่มีกษิดิศ อนันทนาธร และธนากร ทองแดง เป็นแอดมิน) การที่ Pistono ให้ภาพ ส.ศิวรักษ์ ในวัยเด็กโดยละเอียด ในมุมหนึ่งเป็นการเขียนเพื่อหาภูมิหลังของบุคคลโดยดูที่พ่อแม่ และสภาพแวดล้อมของเขา ซึ่งชีวิตส.ศิวรักษ์ ก็อยู่ในการเติบโตยุคที่มีการเปลี่ยนแปลงการปกครองใหญ่ สนามทางความคิดทั้งนิยมเจ้าและไม่นิยมเจ้าแบ่งฝ่ายกันชัดเจน ส.ศิวรักษ์ ได้อิทธิพลจากพ่อและเจ้าคุณอาจารย์วัดทองนพคุณของเขาทำให้เขามีแนวโน้มมาทางอนุรักษ์นิยม ชื่นชมบุคคลต่างๆในสถาบันกษัตริย์ (เช่น กรมดำรงฯ ต่อมาเมื่อเขาเจออารยธรรมตะวันตก เขาไปหา อาณาจักรโรมัน อารยธรรมกรีก มากกว่าจะเดินตามยุคภูมิธรรมและเหตุผลนิยมที่เป็นกระแสหลักในยุคของเขา) มากกว่านักเรียนหัวนอกอย่าง ปรีดี พนมยงค์ และคนอื่นๆ

หนังสือเล่มนี้ยังอาจจะทำให้ผู้อ่านเห็นความเป็นมนุษย์ที่เห็นอกเห็นใจ ส.ศิวรักษ์ มากกว่าที่เขาจะยอมรับกับผู้อ่านในงานเขียนโลกภาษาไทยของเขา กษัตริย์ภูมิพล เคยจ้างนักเขียนที่พระองค์ชื่นชอบมาเขียนชีวประวัติของพระองค์ แต่สิ่งที่พระองค์สารภาพออกมา นักเขียนก็เขียนอย่างซื่อสัตย์ ได้ทำให้งานเขียนเล่มนั้นซึ่งทีแรกจะตีพิมพ์ขจรขจายบารมีของพระองค์ (พวกผู้มีบารมีต่างๆในโลกก็ชอบจ้างให้คนมาเขียนประวัติตัวเองเผยแพร่ได้ในต่างประเทศ แต่ภายในประเทศไทยนั้น ซึ่งความจริงบางอย่างควรจะซ่อนอยู่ใต้พรมก็ทำให้หนังสือเล่มนั้นเป็นอันต้องห้าม ไม่ใช่แค่กษัตริย์ภูมิพล ที่พูดความจริงตรงไปตรงมากับฝรั่งมากกว่าจะพูดกับคนไทย ส.ศิวรักษ์ เคยเล่าให้ผู้เขียนฟังว่า ถนัด คอมันตร์ เองก็ต้องบินไปฝรั่งเศสเพื่อพูดคุยกับคนฝรั่งเศสบ้าง หรือกรมหมื่นนราธิปพงศ์ประพันธ์ก็สะดวกพระทัยคุยภาษาอังกฤษกับ ส.ศิวรักษ์ ที่มีความยุ่งยากทางราชาศัพท์น้อยกว่า

บางเรื่องในประเทศไทย การพูดยังเป็นสิ่งต้องห้าม Roar ก็อาจจะมีลักษณะในเชิงหนึ่งคล้ายกับหนังสือของสตีเวนสัน ซึ่งผลลัพธ์ก็อาจจะปานๆกันคือ ไม่สามารถแปลเป็นภาษาไทยได้อย่างถูกกฎหมายในประเทศไทย แต่นี่ไม่ใช่ในเชิงว่าบุคคลสารภาพเรื่องส่วนตัวออกมาจนไม่อาจจะเผยแพร่ได้เพราะจะทำให้บารมีที่สร้างไว้สั่นสะเทือน หากเป็นในเชิงการเล่าเรื่องประวัติศาสตร์สังคมการเมือง และสถาบันพระมหากษัตริย์ ซึ่งแม้ Pistono จะอ้างว่าตัวเองหาข้อมูลมาเอง แต่ส่วนใหญ่ก็คือการเล่าเรื่องแบบ ส.ศิวรักษ์ (ดูจากการเน้นปรีดี พนมยงค์ หรือ หลายข้อความเป็นการมองแบบ ส.ศิวรักษ์ ซึ่งมีลักษณะพูดถึงความสัมพันธ์ของตัวแสดงทางการเมืองบางตัวอย่างโดดเด่น) ในส่วนท้ายของหนังสือด้วยแล้ว น่าจะพูดสิ่งที่ส.ศิวรักษ์ อยากจะพูดต่อพระมหากษัตริย์ในรัชกาลปัจจุบัน ซึ่งเราจะไม่เห็นเขาพูดแบบนี้ได้เลยในโลกภาษาไทย แม้เขาจะได้ชื่อว่าเป็นคนตรงไปตรงมา ที่ไม่ยอมค้อมหัว แต่โลกภาษาไทยก็ยังจำกัดเสรีภาพบางอย่างของเขาอยู่

แม้เขาจะเลิกทำสังคมศาสตร์ปริทัศน์ แต่อย่าลืมว่าเขาทำหนังสือตลอดชั่วชีวิต เขาเป็นบรรณาธิการหนังสืออีกหลายเล่ม และวารสารอีกหลายฉบับ (หนึ่งในนั้นและทุกวันนี้ก็เช่น Seeds of Peace และปาจารยสาร ในการอุปถัมภ์ของเขา) การเป็นบรรณาธิการของส.ศิวรักษ์ หล่อหลอมบุคลิกภาพโดยรวมของเขาการเป็นบรรณาธิการหนังสือที่เกี่ยวข้องกับสังคมการเมืองในแนวทางเสรีนิยม คือ การรับฟังความคิดเห็นที่หลากหลาย มิใช่ยึดมั่นในลัทธิคำสอนใด (นี่กระมังทำให้เขาชอบยั่วให้แย้ง หรือเห็นว่าเสรีภาพเป็นพื้นฐานประชาธิปไตยกว่าการเลือกตั้งเสียอีก) ยังให้เขารู้สึกการต้องเป็น Intellegenzia คือ คนที่ต้องใช้ความรู้ของตนเพื่อประโยชน์สาธารณชน จริงๆคำว่า “ปัญญาชนสยาม” ที่คนอื่นและตัวส.ศิวรักษ์ เรียกตัวเขาก็น่าจะอยู่ในข่ายของความหมายนี้ ไม่ใช่ปัญญาชนแบบทั่วๆไปที่สนใจแต่สิ่งเฉพาะเจาะจง หากต้องโยงใยให้เห็นภาพรวมและเปลี่ยนแปลงสังคม บรรณาธิการไม่ได้หยุดแต่ที่หนังสือ แต่เขาบรรณาธิกรงานทั้งหมดในชีวิตของเขาด้วย องค์กรต่างๆที่เขาสร้างประสบความสำเร็จและล้มเหลวจากเครือข่ายบุคคลจำนวนมากมายที่เขารู้จัก เลือกสรรมาใช้ ส.ศิวรักษ์ เคยกล่าวว่าบรรณาธิการต้องเป็นเผด็จการ เพราะต้องตัดสินใจในที่สุด

คนจำนวนไม่น้อยเห็นว่า ส.ศิวรักษ์ ย้อนแย้งในตัว แม้ผู้อ่านในโลกภาษาอังกฤษหลายคนก็งงกับการที่เขาว่าติช นัทฮันห์ หรือไปสอนทะไลลามะอย่ากินโค้ก แต่ตัวเขาก็มีสถานะเป็นชนชั้นนำในสังคมของสังคมไทย คำถามหนึ่งที่น่าถามจากการอ่านชีวประวัติเล่มนี้คือ แท้จริงแล้วนั่นคือความย้อนแย้ง หรือความเป็นจริงของชีวิตมนุษย์ที่ทุกคนต้องพานพบ หากมันเด่นชัดออกมาในคนที่เลือกจะให้ตัวเขาเล่นหัวโขนเป็นบรรณาธิการชั่วชีวิต! เท่านั้นเอง Pistono ให้ ส.ศิวรักษ์ “สีหนาท” (Roar) ออกมา นี่คือการตีความของผมจากการที่ข้าพเจ้าได้สดับมาดังนี้ เป็นหน้าที่ผู้อ่านคนอื่นๆจะฟังและเลือกตัดสินใจเอง

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss

Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal is a democracy activist and a student from the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University.

Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal is a democracy activist and a student from the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University.