Irene Stengs, Worshipping the Great Moderniser: King Chulalongkorn, Patron Saint of the Thai Middle Class

Singapore and Seattle: NUS Press and University of Washington Press, 2009. Pp. xiii, 316; photographs, notes, bibliography, index.

Reviewed by Erick D. White.

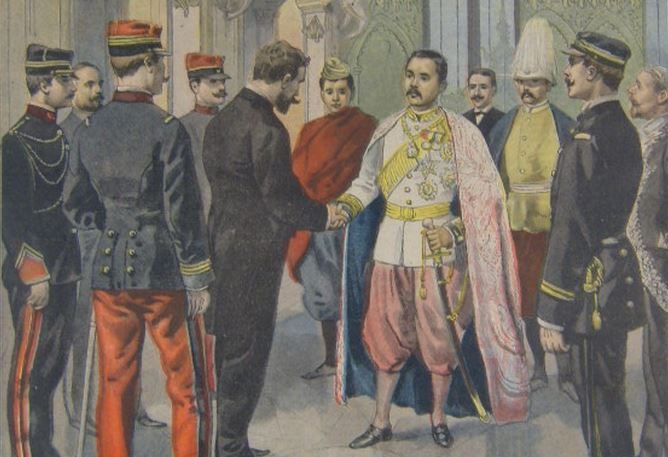

The dramatic heyday of the cult of Chulalongkorn has passed. Arising in the early 1990s, in the middle of the Thai economic boom that lasted from the mid-1980s until the crash of 1997, its prominence has nonetheless persisted into the post-crash 2000s and beyond. Along the way it has gradually declined from a feverish public passion into an accepted and persistent modality of faith and ritual on the kingdom’s mainstream religious landscape. Bangkokians still gather at the Equestrian Statue on the Royal Plaza on Tuesday evenings to show their devotional respect. Practitioners across the nation still petition the deceased monarch before his statues in a myriad of temples and public spaces. Consumers still buy amulets and portraits of Chulalongkorn to adorn their bodies and home altars. Spirit mediums are still regularly possessed by the monarch and thus able to offer advice and assistance to those in need. But since the dramatic emergence of the cult in the heady boom times of the 1990s, other devotional movements, centered on other deities (Princess Suphankalaya and Jatukamramathep, for example) have by now come and gone, part of the relentless churn of religious innovation and inspiration that characterizes popular religiosity in contemporary Thailand. That devotionalism to Chulalongkorn remains popular is not surprising: it is centered on a Chakri monarch in an age of high royalist revival and continuing, if more contested, general public reverence. Nonetheless, the cult of Chulalongkorn no longer evokes quite the same excitement, quite the same breathlessness, or quite the same exuberance. The cult of Chulalongkorn also does not evoke scholarly investigation and analysis as it once did.

And yet its settled, conventional, accepted, and taken-for-granted status as a devotional movement is itself instructive about not only contemporary Thai religiosity and social change, but also the deeper relationship among monarchy, royalism, Buddhism, and popular religiosity in the increasingly unsettled twilight of King Bhumibol’s reign. Irene Stengs’s monograph, Worshipping the Great Moderniser: King Chulalongkorn, Patron Saint of the Thai Middle Class, critically analyses and insightfully opens up for investigation a range of questions about royalty, religiosity, and devotionalism amidst nationalism and consumer society. Her study is based on multi-sited field research carried out between 1996 and 1998 in Bangkok and Chiang Mai. In Bangkok her fieldwork centered primarily on the Equestrian Statue and an organization called the “Prayers Society”, while in Chiang Mai she focused on a temple that was a center of Chulalongkorn worship as well as the abode of a spirit medium possessed by the king.

The study’s long incubation allowed the author to step back and take a somewhat more measured approach, one informed by the passage of time and new or additional scholarship. As a modestly revised version of her dissertation, the monograph’s substance and argument retain much of their original thematic focus and analytic tack, with a limited number of topics expanded or highlighted.

The remainder of this review is accessible here.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss