Ito Tomomi, Modern Thai Buddhism and Buddhadasa Bhikkhu: A Social History.

Singapore: NUS Press, 2012. Pp. ix, 389; maps, figures, notes, bibliography, index.

Reviewed by Patrick Jory.

…Attachment to our own views of the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha [could] block the way to the truth…

Buddhadasa, lecture, 1949

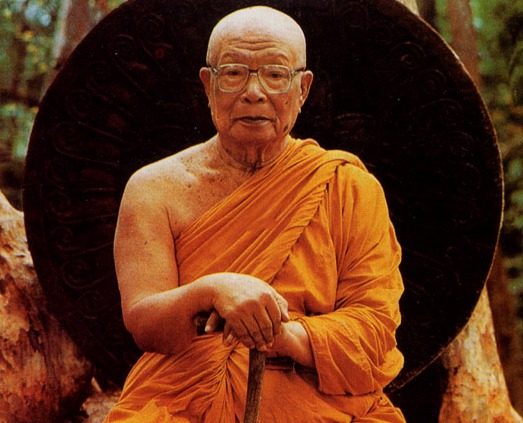

With a population approaching 70 million people of whom around 90 percent are nominally Buddhist, Thailand counts among the world’s most populous Buddhist countries. Of the five officially Theravada Buddhist countries Thailand has the largest number of Buddhists. Yet in the international scholarly literature on Buddhism Thailand is poorly represented. The impact of Thai Buddhist scholars on the broader Buddhist world is similarly limited. One exception to this rule is the work of the monk Buddhadasa (1906-1993). His writings have been translated into English and other languages. He has been the subject of a steady stream of academic studies by international scholars of Buddhism. Donald Lopez lists him as one of thirty-one Buddhist thinkers globally who have helped construct “modern Buddhism” (p. 2). He has even been officially listed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as one of the world’s “great personalities”. Buddhadasa is thus one of Thailand’s very few public intellectuals of international repute. This contrast between Buddhadasa’s international prominence and the relative obscurity of Thai Buddhism on the academic landscape is partly due to the reputation that his work has for embodying a “rational” approach to the study and practice of Buddhism. His greatest supporters, both in Thailand and in the international scholarly community, have been broadly speaking, the educated, liberally-inclined middle-class, the historical bearers of rational thinking but a politically weak minority within the monk’s own country. It is interesting, therefore, to consider Buddhadasa’s career in the context of this Buddhist country’s problematic and unfinished transition to a modern bourgeois society over the course of the twentieth century. This is the theme that Ito Tomomi attempts to develop in this new book on the famous monk.

Ito’s study presents a picture of the scholar-monk as a pugnacious modernizer, engaged in all the intellectual and political battles of the day. It is important first of all to acknowledge Buddhadasa’s membership of a rising Thai nationalist bourgeois elite. He was born in 1906 into a wealthy provincial family in the comparatively prosperous southern province of Surat Thani. His father was a well-to-do assimilated Chinese merchant and his mother the daughter of a middle-level ethnic Thai provincial official. His younger brother and long-time intellectual collaborator “Yikoe”, who later took the name of Dhammadasa, attended the elite Suan Kulap College in Bangkok as one of only around 2800 students in the entire country in the mid-1920s to complete secondary school (pp.31-32). He went on to study medicine at the newly established Chulalongkorn University. Buddhadasa’s own formal education was curtailed after the third year of secondary school because of the death of his father and the need to run the family shop. However he continued his education informally. Besides studying the textbooks for nak tham examinations and other Buddhist works, he read the writings of anti-establishment figures critical of monarchical absolutism such as Thianwan, K.S.R. Kulap, and even Narin Phasit (the subject of a biography by Peter Koret, recently reviewed in this TLC/New Mandala review series by Dr Arjun Subrahmanyan). He taught himself English and subscribed to English- language Buddhist journals, later even translating works on Buddhism from English into Thai. He ordained in 1926 at the age of 20 and moved to Bangkok to continue his Pali studies to the Parien 3 level, before abandoning his formal studies and returning to Surat Thani in 1932 (pp. 30-33). Buddhadasa was thus partly self-taught. Along with his social background, this factor helps to explain the independence of his thinking and his characteristic tendency to attack the status quo.

As Buddhadasa’s reputation as an original, progressive thinker grew, he became acquainted with and gained the patronage of the most influential political and intellectual figures of his generation. These included the leader of the People’s Party that brought Siam’s absolute monarchy to an end in 1932, Pridi Phanomyong (1900-1983); lawyer and later prime minister and privy councillor Sanya Dhammasakdi (1907-2002); leading jurist, later Supreme Court president and minister of justice Phraya Latphli Thammaprakhan(1894-1968); Supreme Patriarch Wachirayanawong (1872-1957); the controversial senior monk of the Mahanikaya order and a later supreme patriarch, Phra Phimonlatham (Aat) (1903-1989); the Marxist journalist and intellectual Kulap Saipradit (1905-1974); and, later in his life, the social critic Sulak Sivaraksa (b. 1933), to name just a few.

Buddhadasa shared the idealistic aims of this generation. For example, he was heavily involved with the Buddhist Association of Thailand, which had been established in 1934 – two years after the overthrow of the absolute monarchy – by figures associated with the People’s Party. The Association was seen in some quarters as having been founded in order to counter royalist domination of the Thai sangha at a time of intense political conflict between the People’s Party and supporters of the old absolutist regime. The Association also had a greater focus on the lay community, which Buddhadasa must have identified as being where the future of Buddhism in Thailand lay, rather than with the community of monks, the traditional concern of the sangha. In his concern for lay practice and his sometimes fraught relations with the sangha establishment, Buddhadasa can therefore be seen as an early “secularist”. Buddhadasa’s sympathy with the political aims of the Association and the People’s Party was also clear. For example, in 1947, and with Pridi in attendance, he gave a lecture entitled, “The Buddha’s Dhamma and the Spirit of Democracy” (p. 70). His temple, Suan Mokkh, was founded in the same year as the Revolution of 1932, in Buddhadasa’s words, “a sign of a new change in order to make things better…” (p. 38).

Buddhadasa’s stance made him many enemies, both within the sangha and without. His radicalism earned him quite early in his career the accusation that he was a “communist” (p. 70). His association with figures on the left like Pridi, Kulap and the British-trained mining engineer and philosopher Samak Burawat, and his development of the concept of “Dhammic Socialism” (pp. 188-215) during the Cold War era, did little to counter this particular attack on his reputation. His open assault on Abhidhamma studies (pp. 137-161), which enjoyed growing popularity in Thailand from the 1950s onward, seemingly in parallel with the rise of reactionary politics during that period, earned him the ire of influential supporters of this school, both lay and monastic. In a famous lecture in 1971 Buddhadasa condemned contemporary Abhidhamma studies in Thailand for overemphasizing the sacred and supernatural, for packaging themselves as “consumer goods”, and for leading their supporters into “delusion and addiction” (p. 159). Buddhadasa also clashed with Kittivuddho – a monk who became famous for his support of anti-communism and his association with the Thai far right – ostensibly over issues of doctrinal interpretation. Buddhadasa’s most famous critic was the arch-royalist and minor aristocrat-politician Kukrit Pramot, who attacked the monk for decades in his newspaper Sayam Rat, including with the claim that Buddhadasa’s ideas were a risk to national security (p. 119). Again, while the disagreement was outwardly over religious doctrine, there was a clear political subtext. Defending the monk from Kukrit’s attacks, one of Buddhadasa’s publishers and strongest supporters, the former high-ranking diplomat Pun Chongprasoet, wrote, “… [People] are deluded to be afraid only that communists will destroy Buddhism when someone of the capitalist and sakdina [feudalist] class is openly destroying Buddhism in this way…” (p.120)

Ito’s book thus helps us to understand Buddhadasa’s work as part of the progressive worldview held by a class of statesmen and intellectuals who shaped Thailand in the mid-twentieth century – figures whose legacy has been marginalized under the royalist-military hegemony which developed in the late 1950s and continues to exercise political and intellectual influence today. Indeed, compared with the ideals of the People’s Party or the Thai left, arguably it is Buddhadasa’s influence, couched in the “indigenous” and therefore familiar intellectual form of Buddhism, rather than the perceived “foreign” Western liberalism or Marxism, which has best survived this era.

Modern Thai Buddhism and Buddhadasa Bhikkhu is a rich and extensively researched book. It contains an enormous amount of material that will be of value to the student of Thai Buddhism in general and of Buddhadasa in particular. Nevertheless, some criticisms can be made. Ito is on occasions a little too admiring of her subject. At times she risks appearing too willing to come to the monk’s defence. The book also bears the traces of the thesis from which it originated, with the understandable desire to include every interesting piece of information that has been found in researching it. But for this reviewer perhaps the main criticism that can be made is the hesitation to fully affirm Buddhadasa’s political affiliations – and even sometimes apparently to deny them. There is a sense that as a Buddhist monk Buddhadasa was above the “worldly” realm of politics. For example, Ito writes, “Buddhadasa’s reference to sangkhomniyom [socialism] in combination with the dhamma should not necessarily be interpreted as a sign that he was inclined toward leftist ideologies…” (p. 193). Yet the author herself has provided much of the evidence that supports just such an interpretation. Despite the fierce independence of his views, Buddhadasa was clearly, like many of the modernizers of his generation, a man of the left with a modern progressive agenda, even if his ideas were expressed within a Buddhist idiom – the idiom which perhaps resonated more deeply with an educated Thai public than the foreign conceptual language of political economy.

How influential are Buddhadasa’s works in Thai Buddhism today?

While publishers continue to reprint Buddhadasa’s works and bookstores display them prominently, it is the less rational beliefs and practices that tend to characterize contemporary Thai Buddhism, and that have attracted the attention of scholars in recent years. Such things include the phenomenon of “commercial Buddhism”, the plethora of cults and rituals, the worship of an ever-expanding pantheon of gods and spirits, and the diverse beliefs in the supernatural which Buddhadasa once derided, now collectively referred to as “practiced Buddhism” – which have been brilliantly analysed by Justin McDaniel in his The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk (2011, reviewed a year ago in the TLC/New Mandala series by Erick White). While it may be argued that these beliefs and practices have been associated with Buddhism since time immemorial, it is hard to deny that the contemporary character of Thai Buddhism owes at least something to the fossilization of a century-old system of monastic administration under a gerontocratic and semi-feudal monastic bureaucracy, to the atrophication of “village Buddhism” due to the slow death of the village society that once sustained it, or to the strange detour to the irrational that large sections of the Thai middle class took in the Bhumibol era, for example in supporting politically reactionary movements like Santi Asok or the enormously successful Dhammakaya temple network, whose abbot purports to have knowledge of the heavenly realm in which Steve Jobs has been reincarnated.* It is tempting to ask whether Buddhadasa’s efforts to reform Buddhism in Thailand, as with other aspects of the country’s political, cultural and intellectual modernization, have been a failure.

Such an environment is not conducive to producing intellectuals of international calibre. Ito’s book reminds us of an era and a political and intellectual milieu which were.

Patrick Jory is Senior Lecturer in Southeast Asian History at the University of Queensland.

Reference

*What is perhaps more surprising than the abbot’s claim is that it was reportedly made in response to a question sent to him from a senior Apple software engineer, Tony Tseung, apparently a follower of Dhammakaya, from Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino, California < http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/08/21/steve-jobs-afterlife-known-by-buddhist-cult_n_1818716.html>.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss