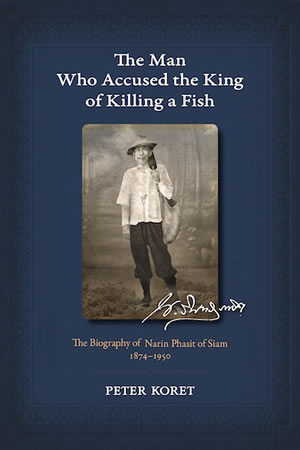

Peter Koret, The Man Who Accused the King of Killing a Fish: The Biography of Narin Phasit of Siam, 1874-1950

Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2012. Pp. xviii, 397; photographs, notes, bibliography of Narin’s writings, index.

Reviewed by Arjun Subrahmanyan.

In his back-cover endorsement of Peter Koret’s new biography of Narin Phasit, Sulak Sivaraksa observes that only three turn-of-the-twentieth-century Thai commoners gained renown as social critics and opponents of the royal-aristocratic establishment. Thianwan (1842-1915), perhaps best described as a publicly committed moral philosopher, advocated for a modern and quasi-democratic political system that would enlighten the populace. K.S.R. Kulap (1834-1913?) also challenged royalist power, especially through his reinterpretation and rewriting of old and venerable historical texts, scholarly endeavors that questioned the official narrative of Thai history. Additionally, Kulap was a witty critic of the Bangkok upper classes, who at the turn of the century had eagerly adopted foreign tastes and styles in clothing and consumption, which Kulap found slightly ridiculous. Both men ran afoul of the authorities for their literary effrontery: Thianwan spent many years in jail, and Kulap was sent to a mental asylum.(1) Narin (1874-1950), the third of the radical triumvirate, also criticized the establishment and spent time in prison for his bold attacks. Narin, however, wrote considerably more, and in a much more colorful style, than either of his elder fellow travelers. At the same time, to a much greater degree than the other two men, he remains an obscure figure in Thai history. Dr. Koret – a scholar of Thai and Lao history and of Buddhism in Southeast Asia – should be commended for presenting for the first time in English a detailed biography of Narin that captures his brash personality, his arrogance and his seemingly unslakable desire to offend important people.

Narin’s adult life is the subject of Koret’s biography, but we can give a bit more background on the man. Narin was born into a modest family of market gardeners in Nonthaburi province in 1874. He grew up amidst the transition from a feudal society, where power lay with the provincial aristocracy, to a nation governed by a modern, centralized bureaucracy and a Westernized Bangkok elite that presided over an internationally oriented market economy. Narin’s career mirrors some of the most important features of early-twentieth-century Siamese society. He rose to a high position in the state bureaucracy by his mid-thirties, and could have enjoyed a bright future and comfortable life in elite officialdom. He also for a time lived as a good bourgeois, investing in and operating a steamship company. As with a later venture in medicinal alcohol sales, however, Narin failed in these approved vocations for a modern Siamese male – state service and useful, responsible work in the emerging market economy – because of a combination of external circumstances and his stubbornly independent personality. Coupled with his assumption of the moral high ground in private and public affairs, these factors led him to champion a series of doomed causes and brought his status as a public nuisance. Narin was a singular personality in a time and place that valued deference to the social hierarchy. He turned his back on the ethics of elite society, and chose to become a social pain in the neck.

Peter Koret explains the content and context of the writings in which Narin advocated for social reform from the 1910s up to the time of the Second World War.

In 1912, Narin established a Buddhist Society and published a magazine to generate interest in preserving Buddhism. He always regarded the religion as in imminent danger of destruction because of people’s faulty understanding of the faith and corruption within the monkhood. Reforming Buddhism, in fact, would become a life-long obsession for Narin. Three years later, he established the short-lived Khana yindi kankhatkhan (Pleased to Object Committee) and published the equally transitory magazine Mo Samai (Fitting for the Times) as a platform for his social and religious views. The government of King Vajiravudh (r. 1910-1925) took an intense dislike to him. Beginning in 1917, Narin spent two years in prison for publishing a pamphlet (Sangop yu mai dai, I Cannot be at Peace) that attacked civil officials for incompetence, a diatribe prompted by the government’s failure to stem rural banditry and provide security in the countryside.

Narin’s pamphlets and letters to government officials and newspaper editorials present the historian with a colorful and confusing jumble of commentaries on early-twentieth-century Siam. Like Thianwan and K.S.R. Kulap before him, Narin exploited the growing importance of print in Bangkok society to gain recognition. He tackled a range of issues he thought important. In addition to rescuing Buddhism and promoting rural welfare, Narin called in his writings for improving prison conditions, abolishing the death penalty, fighting against bureaucratic corruption, lowering taxes and creating a healthier economy, as well as for Siam to take an independent international position. Like the other two men who gained literary fame in the first decades of Thai print culture, Narin’s renown developed into a dubious recognition. Despite his constant pledge of working for the social good, the governments of King Vajiravudh, King Prajadhipok (r. 1925-1935) and of the People’s Party (1932-1947), as well as the news-reading public during these years, always regarded Narin as an eccentric and egotistical loner. The ordination of two of his daughters in April 1928, the best known scandal in Narin’s life, epitomized his self-absorbed and reckless manner of operation: society was sick and in need of healing, and only he could offer the remedy. He published his ideas widely to tell as many people as he could about his plans for reform.

Narin had long dreamed of restoring the ancient order of bhikkunis, the female equivalents of the professional Buddhist monks who transmit the faith and act as moral exemplars in Theravada countries. By a method that remains unclear, Narin’s two daughters Sara and Chongdi took vows as female novices (samaneri) and resided at the family’s autonomous temple, Wat Nariwong (“Temple of the Female Lineage”), adjacent to their home in Nonthaburi. The samaneri became a public scandal in a religious culture governed by patriarchy. The conservative leaders of the Sangha railed against Narin, as did much of the public. Thai Num newspaper carried cartoons of Narin and his wife clinging to their daughters’ robes and ascending to heaven, only to be turned away by the god Indra and sent tumbling back to earth.(2) Lak Mueang newspaper opined that he should be executed for treason to the nation and disrespect for the state religion.(3) In 1929, the police forcibly disrobed the girls and sent them to prison. Later, however, and under Narin’s custody, they reappeared in public with new robes imported from Japan and continued their pursuit of the professional religious life.

Dr. Koret covers this saga in an extended section of his biography, accounting for about one third of the study. He quotes extensively from Narin’s own book on the scandal. Also, Dr. Koret uses his interviews from the 1990s with Narin’s daughter Sara to describe the episode. While the glimpses that Sara offers of the times are enticing, this reviewer at least wishes that Dr. Koret had made more extensive and critical use of the interviews to bring the dramatic events in the samaneri movement to life. It is not clear, for example, how much the girls were sincerely religious and how much they were tools for Narin’s ambitions, or what Narin’s wife thought of the drama.

The samaneri movement faded from public view around 1930, but like the epithet the “thorn in the side of the nation” used by the authorities to describe him, Narin did not go away. In 1933, he publicly attacked the constitutional government’s decree of forced labor for those who could not pay the poll tax in his pamphlet “Thai mai chai that” (Thais are not Slaves).(4) This again landed him in jail, where Narin embarked on a hunger strike to protest his incarceration. (One of the photos that Dr. Koret has included shows Narin in prison during the protest looking like a Siamese Mahatma Gandhi, very thin and dressed in a loincloth.) Later that year, Narin criticized King Prajadhipok for attacking Pridi Phanomyong and his socialist economic plan. Narin argued that the government could hardly condemn Pridi for writing a plan that they had commissioned, and he further alleged that the king had demeaned the monarchy by engaging in politics.(5) He also attacked the People’s Party government for its failure to create a real democracy, and accused them (rightly) of limiting political power to themselves because they were afraid of the prestige of the old ruling class.(6) During the Second World War, in a pamphlet that still reads as shockingly provocative today, Narin attacked Siam’s military dictator and prime minister, Po. Phibunsongkhram. In his arrogant and foolhardy way, Narin called for Phibun to resign since he was an immature bully who did not serve the best interests of the country. Phibun, Narin wrote, should give his power to Narin until the latter decided that Phibun is mature enough to handle it! In a time when the military dictatorship became extremely sensitive to criticism, it is amazing that Narin lived until 1950. In today’s climate, he would almost certainly have been executed, assassinated or imprisoned till the end of his days.

Peter Koret’s book brings Narin to life and is to be commended for rescuing this fascinating man from obscurity. For this reviewer, however, its style and manner of presentation make for difficult reading. As he writes in the introduction to The Man Who Accused the King of Killing a Fish, Dr. Koret has not written an academic study of Narin or a conventional biography. Instead, as he describes it, he has constructed a piece of “creative non-fiction” (page xvii). He has inserted fictitious scenes and hypothetical dialogues into the narrative, presumably in an effort to enliven the story. The book’s opening chapter, detailing events at the end of Narin’s bureaucratic career in 1909, intersperses italicized paragraphs describing events in the Buddha’s life, for, as Dr. Koret asserts, “Narin’s tale is in many ways comparable to the life of the Buddha” (page 2). This strange and rocky beginning is distracting, and it is not clear what the goal is. The author’s style throughout is witty, playful and at times overblown. Chapter headings give the reader an idea of what she or he is in for, such as “The skillful use of thunderbolts, both real and imagined” (Chapter One), “An enraged feline with long-reaching claws” (Chapter Four), and “The future forecast in the handkerchief that this woman clutches in her clenched-up palm” (Chapter Nineteen). Many of the chapter headings and much of the stylistic bombast are drawn directly from Narin’s own writings. Prompted by Narin, it seems that perhaps Dr. Koret is laboring under the fallacy of the imitative form: when writing a book about a man regarded by his peers as unstable, the author must replicate the subject’s zaniness in the narrative. The meandering style, while often entertaining, gets tiresome, at least for the academic reviewer. For these reasons, readers of the Thai language may still be better served by Sakdina’s more straightforward 1993 biography of Narin.(7)

Nonetheless, Dr. Koret has assembled an impressive bibliography of Narin’s own writings, almost all of which are very hard to find. This, coupled with his interviews of Narin’s daughter and his unending enjoyment of Narin’s splendid non-conformity, give twenty-first-century readers a rare portrait of an even rarer Thai commoner who challenged state power and official culture, and whose mentality eludes standard ascriptions to historical circumstance.

Arjun Subrahmanyan is Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History, Utah State University.

Notes

1. For a comparison of Thianwan and Kulap, see Chai-anan Samudvanija, Chiwit lae ngan Thianwan lae Ko.So.Ro. Kulap [Life and Works of Thianwan and K.S.R. Kulap] (Bangkok: Thiranan Press, 1979). Thianwan’s own writings have been republished in Ruam ngan khian khong Thianwan [Collected Works of Thianwan](Bangkok: Tonchabap Press, 2001). Also see Thanet Aphornsuwan, “Thianwan: panyachon phrai kratumphi khon raek haeng Krung Rattanakosin” [Thianwan: The First Bourgeois Intellectual of Bangkok] and “‘Khwamkaona’ nai khwamkhit khong ‘Thianwan’” [Progress in the Thought of Thianwan], in Thanet, Khwam khit kanmueang phrai kratumphi haeng Rattanakosin [Bourgeois Political Thought in the Bangkok Era] (Bangkok: Matichon Books, 2006). On Kulap, see Craig J. Reynolds, “Mr. Kulap and Purloined Documents,” in Reynolds, Seditious Histories: Contesting Thai and Southeast Asian Pasts (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006).

2. Reprinted in Narin, Thalaengkan rueang samaneri Wat Nariwong [Announcement on the Samaneris of Wat Nariwong] (Bangkok: Thai Club of Japan, 2001 [1929]), p. 115. Most fortunately, modern readers can peruse for themselves Narin’s witty and iconoclastic writing style, as Narin’s book was republished with funding from the Japanese-Thai Friendship Society.

3. Sakdina Chatkun na Ayutthaya, Narin Klueng rue Narin Phasit, khon khwang lok [Narin Klueng or Narin Phasit, the Man who Went against the World] (Bangkok: Matichon, 1993), p. 59.

4. Available in the National Archives of Thailand, SR.0201.8/52. Diligent researchers can use the archives to assemble a more comprehensive picture of Narin than Koret offers. In addition to the Prime Minister’s Office(SR) files such as this one just referenced (which contains official correspondence, Narin’s writings and newspaper coverage of his activities), the Seventh Reign archives (R.7, microfilm) contain a wealth of information on Narin. Especially interesting are his exchanges with the Royal Secretariat and the letters of King Prajadhipok and Queen Rambhai-bharni on the Wat Nariwong controversy.

5. Also see Sakdina, Narin Klueng, pp. 84-85, 142-144.

6. Also see ibid., pp. 81-84.

7. Sakdina, op cit.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss