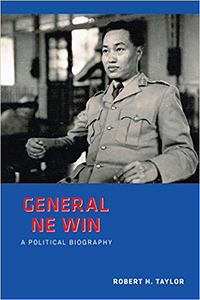

Robert H Taylor, General Ne Win: A Political Biography, (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2015)

Robert H Taylor, General Ne Win: A Political Biography, (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2015)

Reviewed by Frank Milne

Ne Win, the dictator of Burma from 1962 to 1988, looms large in the nation’s modern history and memory. With historic free and fair elections – the first in 25 years – having just taken place, one wonders what he would think of the country today.

As he died while under house arrest in 2002, we can’t ask Ne Win about his nation’s political transformation. However, in Robert H Taylor’s General Ne Win, we are provided with an illuminating and important study of one of Burma’s most controversial political figures.

This excellent biography addresses Ne Win’s career and his place in Burmese political movements in the 20th century. It is a thoroughly researched account of the period. There is less information about his personal life and views outside politics, as he left no collection of papers, and contemporary accounts were mostly written by those who had fallen out with him.

I served in the Australian Embassy in Burma for two separate periods (1963–65 as Second Secretary and 1982-86 as Ambassador) which book-ended the Ne Win period. The earlier period was gloomy, as the economy was dislocated by wholesale nationalisation, political opponents were jailed, political parties banned, and the press strictly controlled. Burmese officials went to ground, and contact with foreigners was restricted.

I had one opportunity to meet Ne Win at a small lunch he gave for the Australian Foreign Minister Paul Hasluck in May 1965. His conversation over lunch was genial but general, though he did not conceal his low opinion of the Burmese people’s capacity for sustained effort, and the need for a firm government hand.

Ne Win was not simply a general who staged a coup d’état as a road to power and fortune. His lifelong commitment was to the unity of Burma and its independence from foreign political or economic control. In the 1930s, well before his military career, he was politically active in the nationalist association Dobama Asiayon pursuing independence from British colonial rule. He was one of the Thirty Comrades trained by the Japanese, to form the nucleus of the Japanese-controlled Burma Independence Army. This later became the Burma Defence Army, which in 1945 turned to the allied side against the Japanese.

In the internal upheavals before and after Independence in 1948, Ne Win, now one of the senior figures in the new Burmese army, played a major part in defending U Nu’s socialist government against ethnic insurgents, and Communist rebels.

Taylor’s book provides a rigorous account of the roller coaster ride that followed.

In 1949, now supreme commander of the armed forces, Ne Win was appointed Deputy Prime Minister and Home and Defence Minister, but resigned his ministerial positions in 1950 to concentrate on the armed forces. His brief cabinet experience gave him distaste for party politicians whom he regarded as preferring self-interest above the national interest. This jaundiced view of politicians was shared by his subordinates in the Army for the next 50 years.

In 1958 a split in the ruling party led to a constitutional crisis. This was resolved in 1959 by Ne Win taking charge as caretaker prime minister to restore order before new elections. Ne Win ensured that the army remained politically neutral, but was not prepared to let the communists come to power, when it seemed that U Nu was prepared to make concessions to win their support. His nonpartisan and technocratic government provided a period of stability, but the 1960 elections won by U Nu’s Union Party did not provide a lasting solution.

Amid growing political unrest and dissension, and concerned for the future of the Union if U Nu were to grant greater autonomy to the ethnic minorities, Ne Win took power in a sudden and largely bloodless coup in March 1962. He did not follow the policy of his previous caretaker government, but embarked on a new socialist revolution and a one party system under his leadership – The Burmese Way to Socialism.

Though he was not a Marxist, and indeed was strongly opposed to the Burmese communists, he regarded Marxist methods as a useful means of establishing the control needed to get the easy-going Burmese people to become self-reliant, develop the country and protect their own culture. He was above all concerned to protect the integrity of the Union of Burma against foreign and domestic challenges.

By 1982 Ne Win had handed over the Presidency to San Yu, though he remained a controlling presence as Party Chairman. He no longer had any contact with foreign missions. The socialist revolution was then running out of steam, and its first rigours were somewhat relaxed, but the economy was at low ebb. The ethnic insurgency rumbled on in the background, though the communists, now confined to the northern border area, now longer posed a serious threat.

In the epilogue summing up Ne Win’s career, Taylor notes that the Ne Win revolution was not bloody but it was admittedly not cost-free. On the credit side he suggests that Ne Win did create a nation with the resilience from its own resources to withstand over 20 years of economic sanctions. He succeeded in his principal foreign policy aim of keeping Burma out of external entanglements and free of foreign political and economic influences, although at the expense of opportunities foregone.

He was prepared to accept the cost of rejecting foreign loans or assistance that came with strings. He did not want Burma to be enrolled in either side in the cold war, with the risk of exposing the country to the sort of great power conflict which ravaged the countries of Indochina. He was equally suspicious of Chinese intentions and the potential for United States interference. He carried his policy of neutralism to the extent of abandoning the non-aligned movement when he considered it had abandoned its founding principles.

His economic policies were not successful. Taylor points out that many social indicators such as literacy, infant mortality and basic health care improved under Ne Win. However such improvement might well have been greater under a more pragmatic economic regime. Partly because of the insurgency, expenditure on the Armed Forces greatly exceeded the funds devoted to health and education. Whether a more flexible government might have been able to negotiate a better and less expensive settlement with the ethnic minorities without breaking up the Union is another question. But Ne Win normally preferred the stick to the carrot.

Taylor notes that by persisting in failed policies long after it became clear that they had failed, the government did less than it could have done to reverse Burma’s economic decline. He suggests that Ne Win knew the policy of Socialist autarchy had failed, but feared the alternative of re-engaging with the world economy, partly because those around him were averse to change and those he had to work with had been cut off from knowledge of the new ideas and new developments in economic theory and the sciences by the country’ self-imposed isolation.

He also feared that the Burmese people, despite cajoling and coercion, might not resist the temptations of a new foreign economic invasion. But a more productive economic policy would surely have been possible without harmful foreign entanglements, if the government had been prepared to listen to better advice.

Despite Ne Win’s genuinely patriotic intentions, the end result of his regime was to keep Burma in a time warp for over 40 years, from which it is only now starting to emerge. The consequences of his political career, make Taylor’s book a must read.

Frank Milne was Australian Ambassador to Burma from 1982-86.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss