Benedict R. O’G. Anderson, The Fate of Rural Hell: Asceticism and Desire in Buddhist Thailand

Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2012. Pp. viii, 99; photographs.

Reviewed by Erick White.

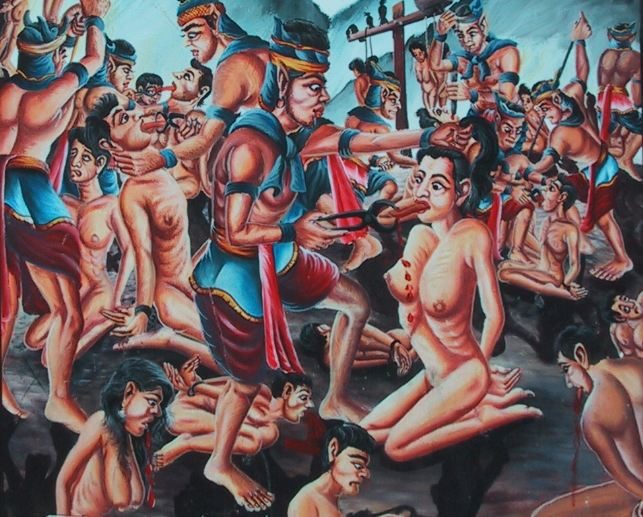

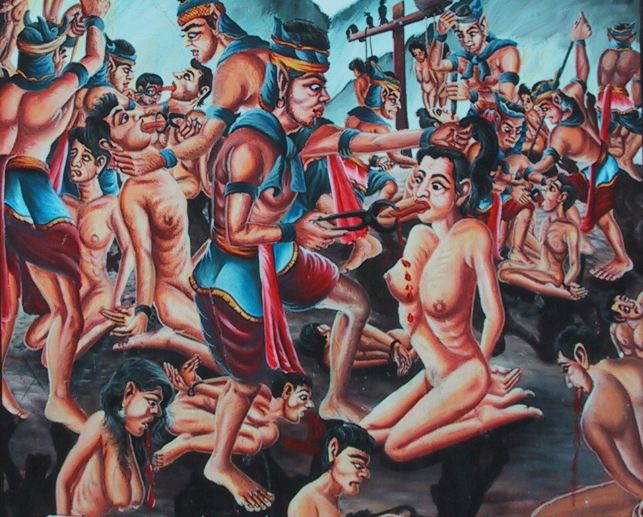

This slender volume, full of many provocative assertions and interpretations, actually constitutes something more like an extended essay than a full-fledged monograph. Its fifty-six pages of thought-provoking text are supplemented by thirty-eight eye-catching photographs which document a cross-section of the statuary that populates the book’s central focus – the “Hell Garden” of Wat Phai Rong Wua, a temple located in a hard to access rural corner of Suphanburi province. These dramatic, grotesque and eroticized three-dimensional representations of the classic Thai Buddhist vision of hell, designed to educate and warn the general public about the future costs of current moral transgressions, serve as a primary empirical foundation for Benedict Anderson’s more general musings about history, religiosity, aesthetics, desire and subjectivity in rural Thailand, past and present. The seed for these extended reflections was planted more than thirty-five years ago in 1975, when Anderson fist visited the Suphanburi temple. Since then he has returned on three occasions, each time collecting additional information about the temple and its phantasmagoric visual spectacle. He has also consulted two Thai master’s theses on the temple. Anderson’s continuing fascination with the temple’s arresting visual extravagance eventually grew into this exercise in “investigating this rural hell within its local and wider contexts” (p. 11).

The Fate of Rural Hell is concerned primarily with three issues: the history and context of the temple and its hell garden, the psychic and motivational undercurrents at play in the creation of the hell garden, and the implications of the hell garden’s seemingly inevitable eclipse as a pedagogical project of piety. In exploring the history and context of the temple and its hell garden, Anderson initially reflects on the statuary itself, and on its anarchic, even sadistic, glorification of the sufferings of impalement, mutilation and torture that await the morally disreputable in their future hellish rebirths. Anderson is especially interested in the explanatory captions painted directly on the statues, cataloguing and categorizing them according to the types of transgressions described, who committed them and against whom they were committed. He notes that the sins depicted are conventional and even generically stereotypic within the Buddhist ethical imaginaire – murder, lying, stealing, adultery, slander, etc. – rather than particularly Thai or contemporary. There are no corrupt politicians, committers of lèse majesté, communists, professional hit men, or selfish capitalists represented in the Hell Garden, for instance. He is also fascinated by the nakedness of the sufferers and the eroticized masculinity of the servants of Yama, the mythological judge of the recently deceased, who are torturing them.

Anderson also reflects on the intertwined history of the temple and the biography of the temple’s late abbot, Luang Phor Khom, both as contextualized within Thailand’s twentieth-century political and religious history. He focuses especially on the history of building projects pursued by the abbot, of which the Hell Garden is just one example. What emerges is a developmental tale of growth, expansion and subsequent decline within an expanding, internationalizing capitalist economy. In the twenty years prior to 1957, Luang Phor Khom established the architectural foundations of a generic rural temple at Wat Phai Rong Wua by building several sermon halls and sleeping quarters, as well as an ubosot (ordination hall), a school house, and a connecting road. But, spurred on by the national and international celebrations of the 2500-year anniversary of the Buddha in 1957, the abbot began to pursue more monumental if conventional devotional building projects, such as a giant seated Buddha and replicas of Indian Buddhist religious sites. These resulted, in turn, in increasing recognition from Bangkok elites and even from the Thai king himself in 1969. This recognition subsequently fueled an expansion in visitors and donations in the early 1970s. This attention and support led to a rapid, but relatively brief, burst of more topically eclectic projects – the Hell Garden included – which were then followed by a winding down of construction over the subsequent fifteen years. By the time of the abbot’s death in 1990, an air of desolation and decay had set in, and the temple carried the burden of enormous, hidden, and mounting debts.

Having examined the historical and social context within which the Hell Garden is embedded, Anderson explores the otherwise unspoken motivational undercurrents at play in the creation and uses of the Hell Garden’s extended visual diorama. Two psychological dimensions are of particular interest to Anderson – the motivations of the abbot and the psychic price of the patronage developed between the abbot and his craftsmen. From Anderson’s perspective, the Hell Garden of Wat Phai Rong Wua is a historically innovative form of visual representation for its time, leaving behind the more muted, conventional interactive medium of murals that preceded it. In particular, Anderson is intrigued by the “anarchic, semi-sadistic eroticism” (p. 60) that he sees as animating the statuary, whose aesthetics was consciously and explicitly specified in the abbot’s detailed instructions to his craftsmen. Ultimately, Anderson argues that the logic underlying the Hell Garden’s dramatic aesthetic vision lies in the abbot’s repressed and sublimated sexual desire and its fantasized phantasmagoric objectification via a “theology of abjection” (p. 90). He even goes so far as to refer to the abbot as “gay” and describes him as “a religious figure struggling in unusual ways to deal with his unorthodox sexuality on the eve of the triumph of a consumerist culture” (p. 93). At the same time, Anderson highlights the erotics of devotional intercession and pleasurable transgressions which are also sometimes at play in the Hell Garden. Individuals seeking improved health at two statues deemed by locals to be endowed with magical power are known to touch their clothed genitals in pursuit of blessing, and some have even danced naked before the statues in petition. Similarly, local boys have been known secretly to masturbate at night before the naked female statues. The Hell Garden, then, is apparently a magnet for provoking and channeling subversive, unspoken, furtive eroticism.

Just as intriguing for Anderson are the complicated social relations between the abbot and the folk artisans who actually built the statuary of the Hell Garden. The craftsmen, Anderson concludes, worked as unpaid or minimally paid modern versions of what an earlier era called “temple slaves”. Under the umbrella of the abbot’s patronage, they were easily exploited, as well as easily disposed of when the building projects wound down. Nonetheless, Anderson identifies an enduring, collusive social indebtedness within the intimate bonds of mutual dependency fashioned under rural patronage. The last surviving sculptor, Suchart, harbors resentment at being trapped in a dead-end and impoverishing occupation and yet acknowledges that, out of deference to Luang Phor Khom, he chose not to carve statues of the hellish fate of corrupt local officials, dishonest monks and crooked temple committee members. In turn, despite Suchart’s fall into alcoholism and drug addiction, the abbot cared for him. After the abbot’s death, his nephew and successor also rescued Suchart from abject poverty by allowing him to ordain despite his un-exemplary behavior. Anderson highlights the intimacy and hierarchy of this social dynamic, the celebration and abjection underlying rural patron-client relations as they play out in complicated ways across an environment of mutually unspoken, frustrated and rejected desire. “It is not hard to conclude that Suchart, who is no one’s fool, understood what drove Luang Phor Khom, maybe even sympathized with it, but he needed the abbot’s authority and patronage. Conversely, his patron was grateful for this tact and for his spectacular statuary and so kept him under his wing” (p. 86).

Anderson concludes his analysis of the Hell Garden at Wat Phai Rong Wua by reflecting briefly on the declining cultural and social salience of the religious aesthetics, pious instruction and devotional inspiration as exemplified within and through the temple’s built environment. The genitalia of some statues are found to have been covered up during Anderson’s most recent visit, while other statues have disappeared, presumably in response to public rebuke. (Even before his death the abbot displayed an ambivalent defiance and shame in the face of public criticisms of the Hell Garden as “pornography”.) The visual message of the park seems out-of-date and rather sedate in the eyes of a contemporary urban youth more familiar with a heady diet of horror films, violent video games and Internet pornography. Physically deteriorating and spatially marginal, the Hell Garden comes across as increasingly irrelevant and backwards in relation to other tourist venues, even as its sacral aura fades. Its particular fusion of kitsch, languor and piety, Anderson suggests, marks it more as an historical museum, as a cultural world out of joint with the wider cultural and aesthetic sensibilities at play in Thailand’s dominant digitized, high-speed mass culture. In short, the models of eroticism and faith at work in the Hell Garden have been left behind to a considerable degree by the robust urban bourgeois consumerist culture increasingly prominent across contemporary Thai society and public life.

This review is available in its entirety here.

Erick White is a doctoral candidate in anthropology at Cornell University. He has carried out research on the subculture of professional spirit mediums in Bangkok. More recently, he served for several years as an instructor in the Antioch Buddhist Studies in India program.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss