Fran├зois Molle, Tira Foran and Mira K├дkönen, eds., Contested Waterscapes in the Mekong Region: Hydropower, Livelihoods, and Governance.

London and Sterling, Virginia: Earthscan, 2009. Pp. xxii, 426; figs. and maps, bibs. by chapter, index.

Two important books on water resources in Asia appeared in 2009. The first is Tushaar Shah, Taming the Anarchy: Groundwater Governance in South Asia (Washington and Colombo: Resources for the Future and the International Water Management Institute). The second is the subject of this review.

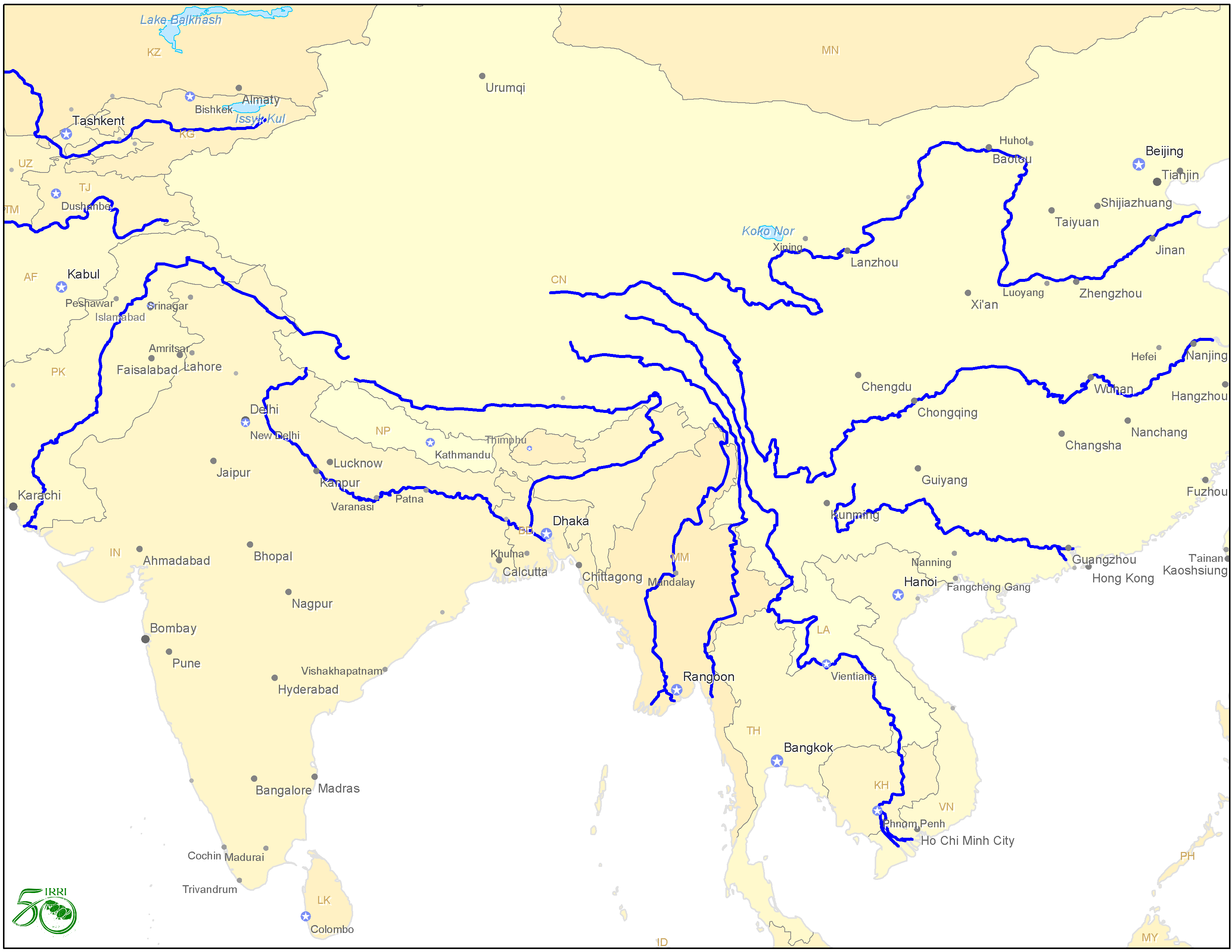

Let me first say something about the importance of the matter at hand. As the International Rice Research Institute map below illustrates, the Himalayan Watershed includes eight rivers, stretching from the Yellow River in China to the Indus in Pakistan. With the exception of the Ganges, all of these rivers have their headwaters in Tibet. Approximately half of the world’s population and half of the world’s poor depend either directly or indirectly on the Himalayan Watershed for their food supply.

Over the last half-century we have developed surface irrigation systems, and exploited or in some cases over-exploited groundwater. There is now little opportunity for further expansion of irrigation. Furthermore, as the volume under review makes very clear, there is growing demand for water for non-agricultural uses–hydropower, urban consumption, and industrial demand. Agriculture, for which approximately 80 percent of water is diverted, will thus receive less and less water in the future. Some observers are concerned with the prospects for global warming and the melting of the Himalayan glaciers. But even without this problem, we will have to move from development to management of water resources. Most Asian governments have not realized the need for this change, let alone considered how it is to be accomplished.

It is against this backdrop that Contested Waterscapes in the Mekong has been written. The book is a product of M-Power (The Mekong Program on Water Environment and Resilience, www.mpowernet.org)–a network of “people committed to improving local, national and regional governance in Cambodia, China, Laos, Burma/Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.” The fact that not just one or two countries but six utilize the water of the Mekong is what makes the Mekong region unique. And the region’s waters are contested not only among countries but also even within countries. These latter contests are among agencies and organizations with particularistic interests in one of the multiple uses of water–irrigation, hydropower, urban demands, the environment. These agencies do not typically talk to one another.

The introductory chapter of Contested Waterscapes, on “Changing Waterscapes in the Mekong Region: Historical Background and Context,” sets the tone for the book with its emphasis both on history and on current challenges and dynamics. Following that introduction, and as the volume’s sub-title implies, the volume is divided into three parts: on “Hydropower Expansion in the Mekong Region,” on “Livelihoods and Development”, and on “Institutions, Knowledge and Power.” The lead-off chapters of Parts I and II (Chapter 2 on “Old and New Hydropower Players in the Mekong Region: Agendas and Strategies” and Chapter 6 on “Irrigation in the Lower Mekong Basin Countries: The Beginning of a New Era?”) provide good overviews. They are followed in each instance by a series of focused case-study chapters. Part III covers a range of issues, including “The Anti-Politics of Mekong Knowledge Production” (Chapter 13) and “Demarginalizing the Mekong River Commission” (Chapter 14). The final chapter, Chapter 15 on “Contested Mekong Waterscapes: Where to Next?,” serving as a review of the book’s findings. That last chapter also offers somewhat dubious suggestions for future directions in the governance of the water resources of the Mekong region.

I found this book fascinating from a number of perspectives. First, it is very informative on a range of issues. It includes a great deal of information on the politics of dam development for both hydropower and irrigation. Second, there are a useful set of maps and tables locating and defining both completed and planned dam projects. Third, the fifteen chapters are conspicuously well written. Given the fact that thirty-seven co-authors contributed to Contested Waterscapes, we must give credit to the editors for their fine work. Even a reader well versed in various aspects of water resource development and management will find this book a valuable reference.

Each of the case-study chapters, which cover a wide range of topics, stands alone on its merits. For example, you may be surprised at how many dams are in operation or being proposed or in the planning stage in the upper reaches of the Mekong and Salween in China (Chapter 2 and also Chapter 5, on “Damming the Salween River”). The fruitless effort of the Thai government to irrigate the Northeast–“the Green Isan” project–is described in Chapter 10, on “The ‘Greening of Isaan’: Politics, Ideology, and Irrigation Development in the Northeast of Thailand”. The unfulfilled promise of flood protection places the populations of cities such as Bangkok, Hanoi, and Ho Chi Minh City in a continuously vulnerable position (Chapter 11, on “The Promise of Flood Protection: Dykes and Dams, Drains and Diversions”).

Then one comes to the concluding chapter. Here I again mention Tushaar Shah’s book dealing with groundwater management in South Asia. Although the problems are different, the conclusions of these two books are strikingly similar. Entrenched bureaucracies, vested interests, and financial support from international donors and other sources dictate that countries (and in India states the size of countries) continue to focus on the construction of new or the rehabilitation of old irrigation systems. Management of water resources and related social and environmental concerns continue to be ignored. As this last chapter of Contested Waterscapes notes, “the proceeding sections convey a rather bleak picture of the governance of water resources in the Mekong region … with hard core developers pitted against activists” (p. 398).

This book, while pointing out the skewed allocation of resources in favor of the developers, takes a middle road. Its concluding chapter sets out five paths to improved water governance, each of which can be found in the contributions to the volume. These are, briefly: (i) co-producing knowledge, (ii) debating alternatives, (iii) promoting standards, (iv) contesting decision-making, and (v) trans-boundary governance. Each path will attract a different clientele, depending on expertise and interest. However, it is not clear to me how choices from this range of alternative paths will collectively move us toward improved governance of water resources in the Mekong region.

What is missing from Contested Waterscapes is attention to the importance of growing water scarcity and its implications for where we go from here. The five co-authors of Chapter 6, mentioned above, find themselves somewhat uncertain whether we have entered a new era since the actions of governments have not changed. But we have indeed entered a new era. It is not just the semi-arid regions of Asia but also the monsoon areas that are beginning to feel the pressures of water shortage for agriculture as the demand for non-agricultural uses grows. Over the past half century, as indicated earlier, we have fully played the surface irrigation card and subsequently the ground-water card. There will thus be more pressure to manage our water resources. Conflicts will certainly arise as food security once again moves onto the agenda of many countries in the region. An objective of research should be to determine how much of the 80 percent of the water diverted for agriculture is beneficially depleted in crop and livestock production–or in short how much is wasted through evaporation or other means.

Parenthetically, it should be noted that the concerns raised in Contested Waterscape apply not only to Mainland but also to Maritime Southeast Asia. Even without trans-boundary concerns to worry about, Filipinos will realize that the ircountry faces many of the same problems found in the Mekong region, with its “contested waters.” This past January, I joined friends in visiting the Heart of Mary Villa (HMV) Convent, a home for unwed mothers in Malabon, a low lying area on the northwestern edge of Manila. My family adopted two children from HMV in the 1970s. Last October, following heavy rains and a typhoon, water was released from the Angat Dam. The wall protecting HMV collapsed and, like a tsunami, waters quickly rose to a height of some eight feet. Fortunately, the babies were moved to the second floor, and no one drowned. Now, of the four major dams in Luzon, only the Pantabagon has enough water for the dry season to come (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 30 January 2010). Of course, the water from the Angat Dam is gradually being diverted from agriculture to meet the growing needs of urban Manila. Farmers are not compensated, but to draw on groundwater many are purchasing inexpensive low-lift pumps imported from–where else?–China. Asia’s water-scarcity crisis is real, it is widespread, and it is complex.

Finally, I agreed to review the important volume Contested Waters not least so that I would get a free copy. Amazon sells it for $127.50. The editors assure me that after a year or so there will be easier, cheaper access. Meanwhile, I hope that your library can afford to buy it.

Randolph Barker

Professor Emeritus of Agricultural Economics

New York State College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Cornell University

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss